{english below} Algunas personas nacen en el momento concreto y en el lugar adecuado para vivir en estricto directo el inicio de algo mágico. Tal como cantaba el gran Gil Scott-Heron, la revolución no será televisada… aunque algunos afortunados la experimentaron desde sus entrañas. Éste es el caso de Dave Tourjé, un artista multidisciplinar que nació en un barrio mestizo del noreste de Los Ángeles en 1960 y se adentró sin tabúes en la escena del Hot-Rod, también en el mundo del skate, el movimiento punk y, además, lo aderezó todo con una sensibilidad artística que lo ha convertido en uno de los nombres más influyentes del posmodernismo norteamericano en una época de grandes cambios sociales. Su obra pictórica mira hacia el pasado con respeto, consciente de la importancia de todo aquello descubrió hace más de cuatro décadas en las calles de una ciudad caótica que vivía bajo el influjo de las bandas y del surf como forma de vida. Pero también se atreve a imaginar un futuro a base de colores violentos, donde cada trazo nos habla del conflicto y nos anima como espectadores a no callar nada de lo que nos preocupa. Dave Tourjé fue miembro de la influyente banda de punk The Dissidents, ha protagonizado el premiado documental “L.A. Aboriginal” y desde hace unos años también forma parte del colectivo California Locos, junto a eminencias como Norton Wisdom, John Van Hamersveld, Chaz Bojorquez y Gary Wong. Aprovechando que acaba de volver de Virginia Beach donde ha expuesto parte de su nueva obra, hemos tenido la oportunidad de hablar con él para recordar los momentos clave de una carrera que sigue escribiéndose en presente. Es evidente que los tiempos cambian, pero toda revolución tiene un origen. Y éste es el inicio del arte underground de la Costa Oeste.

Siento mucha curiosidad por saber cómo fue crecer en el noreste de Los Ángeles en la década de los 70. ¿Cómo era realmente la vida en tu barrio?

El noreste de L.A era un lugar muy propicio para crecer por diversos motivos, pero sobre todo porque allí convergían la cultura de los blancos de clase trabajadora y la de los mexicanos. Esto causaba cierta tensión, pero también se integraban los dos estilos de vida. Mi madre era de Ciudad de México, así que yo andaba por ambos lados en cierto modo. En ese barrio había una gran tradición de Hod-Rods, de pioneros del motocross (como las familias LeBlanc y Burns) y los chavales empezaron a practicar BMX cuando cortaban la autopista en los años 60. También había el tema de las bandas, incluso algunas de blancos, y la cultura del esquí era fuerte porque entonces había mucha nieve en las montañas locales. Sin embargo, en la costa mandaba la cultura del surf. Y, finalmente, en la década de los 70 se expandió el skate y el snowboard al mismo tiempo que el punk. Bandas como The Gears, X y Top Jjmmy and The Rhythm Pigs vivían en la zona. Sin olvidar que allí estaba el estudio de Hully Gully, donde Los Lobos, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction y todas esas bandas iban a ensayar. Yo ayudé a construirlo con mi amigo Bill Mentzer, que resulta que era también era el propietario. De una manera u otra, yo formé parte de todas estas cosas.

F: John Spielmann

En diversas ocasiones has comentado que una de tus grandes influencias ha sido Diego Rivera. ¿Cómo descubriste sus murales y que impacto tuvieron en tu visión del arte?

Cuando era pequeño, mi madre nos llevó a mis hermanas y a mí a vivir con nuestra abuela a Ciudad de México. Cada día íbamos a pasear por el Chapultepec Park o por algunas calles para jugar o, simplemente, para mirar el arte que había. Fue en la Librería Central que descubrí el primer gran mural de Rivera. Recuerdo que lo miraba y apreciaba la narración que encerraba a base de conflicto, de dolor y de revolución. Estos conceptos se convirtieron en una realidad para mi a través de esa obra. Como yo estaba solo allí, ocupaba mi tiempo dibujando y logré conectar esas ideas basicas: arte y revolución. Entonces supe que debía intentar formar parte de esa narrativa y no ser un simple espectador en el mundo.

¿Qué recuerdos tienes de los inicios del skate en Los Ángeles? ¿Te cruzaste alguna vez con la gente de Dogtown? Tengo entendido que frecuentabas un spot conocido como “The Bowl”…

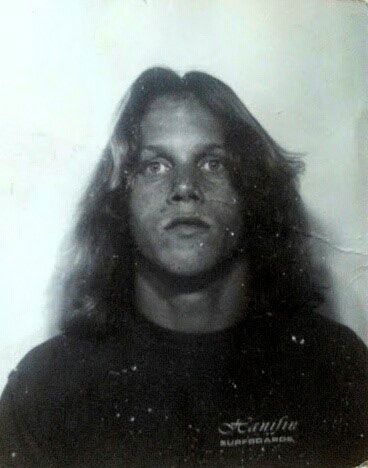

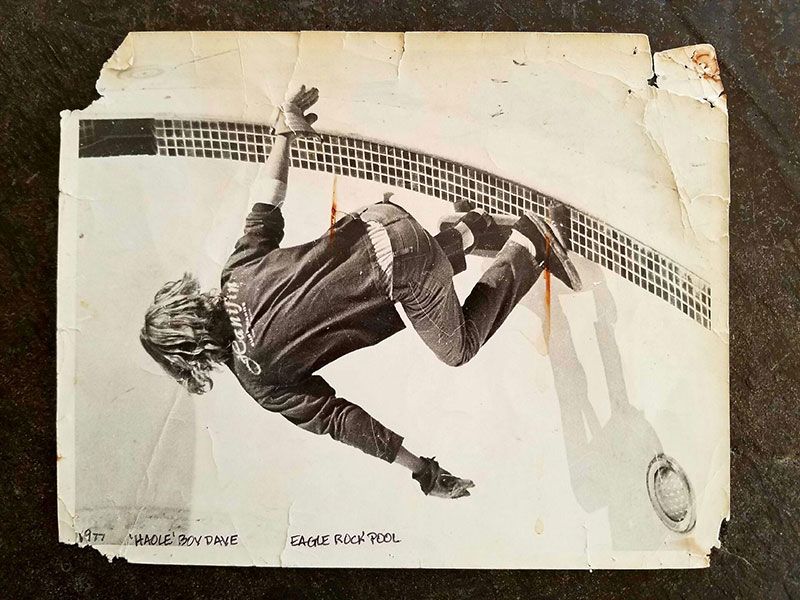

Empecé a patinar en 1967 porque mi padre me compró un patín Black Knight con ruedas de arcilla para mi séptimo cumpleaños. Mis tíos tenían una casa en la playa en Newport Beach y recuerdo que todo empezó a cambiar allí en 1972. Yo estaba en la tienda Hanifin Surfboards de Newport cuando las primeras ruedas Cadillac llegaron. Pat Hanifin las sacó de la caja y me dijo: “Chaval, dile a tu madre que te compre unas de estas”. Y así lo hice. Esto era antes de que aparecieran las primeras revistas de skate y los anuncios. Recuerdo que las monté en mi tabla y no podía creer lo suave que iba y la velocidad que cogía. Cuando regresé a mi casa en las colinas del noreste de L.A, en una zona conocida como Highland Park y Mount Washington, vi que las calles habían sido recientemente asfaltadas y empezamos a mejorar mucho. Poco después encontramos un canal de drenaje al que bautizamos como “The Bowl” y aprendimos a recorrerlo. De vez en cuando, algunos de los Z-Boys aparecían por allí y en cierta ocasión patiné junto a Stacy Peralta y Shogo Kubo. “The Bowl” era un spot secreto, pequeño pero intenso, y resultaba un enorme desafío. Se convirtió en una obsesión ir cada día allá durante varios años… ¡hasta que llegó la sequía, se vaciaron las piscinas y empezó la revolución!

F: Daniel Madero

F: Kevin Regan

F: Steve Guzman

F: Daniel Madero

F: Elliot Mills

También formaste parte de la incipiente escena del punk de la ciudad. ¿Crees que empezó como oposición a todo lo que había sucedido anteriormente? ¿Cuál crees que ha sido su legado?

La película “The decline of western civilization” de Penelope Spheeris cuenta esta historia bastante bien. Sucedían muchas cosas en aquel momento y la ciudad era un caos creativo absoluto. La escena del punk en L.A no era solamente música punk, sino que también incluía country, blues, folk, noise y cualquier cosa que pudieras imaginar. Encontrabas bandas como X, Top Jimmy and The Rhythm Pigs, Black Flag, The Plugz, SST Records y una larga lista de nombres. Visto en perspectiva, fue una revolución norteamericana que bebió de muchas fuentes y todavía hoy se aprecia la influencia monumental que tuvo. Y a nivel personal puedo decir que no se ha vivido de ese modo en ningún otro lugar. Muchos de nosotros estábamos hartos de la música disco y de las bandas de rock con pelos cardados… esa escena fue cosa de gente de clase trabajadora y un mecánico aficionado al punk podía enchufar una guitarra barata a su amplificador para chillar: “¡Qué os jodan!”.

F: Gary Leonard

F: Gary Leonard

F: Gary Leonard

Estudiaste en el Art Center College of Design y después te matriculaste en la University of California. ¿Cómo recuerdas tu época de estudiante? ¿Aprendiste algo que haya resultado útil en tu carrera?

La educación universitaria fue muy útil para aprender lo que no quería en mi vida. Estando sentado en la clase de arte del instituto un sábado de 1977, me di cuenta de que no quería convertirme en diseñador de publicidad, aunque aprendí a dibujar figuras. Y eso me ayudó a plasmar mis visiones. En la UCSB descubrí los entresijos de la educación artística y la odié, así que al cabo de dos años, en 1979, abandoné las clases para tocar música en L.A. Realmente estaba desilusionado con ese tipo de educación y no volví a coger un lápiz en cinco años. Había tenido una educación artística tan buena de crío en casa, con unos padres que me apoyaban, y también en la escuela primaria, que consideraba que ya dominaba las nociones básicas antes de ir a la universidad. Y, una vez allí, me di cuenta de que lo único que conseguiría sería perder el espíritu creativo. Así que lo dejé todo y perdí mi beca… aunque salvé mi integridad artística. Actualmente, creo que soy el único de aquella promoción que sigue haciendo arte, aunque no tengo el título de licenciado. Eso sí, aprendí mucho en un programa de dibujo de señales en el centro ocupacional West Valley un par de años más tarde. Y eso es a lo que me dedico ahora, crear símbolos en el campo del arte.

Tus obras han sido alabadas por “la violencia de sus colores” y también por “el simbolismo de sus formas”. ¿Qué buscas cuando trabajas en una pieza? ¿Te sientes cercano al espíritu del Pop Art?

Creo que, en cierta manera, sí que estoy conectado al Pop Art. El giro posmoderno que se vivió en la década de los 60 se basaba en que la noción de la existencia de los gestos impulsivos “no planeados” dio lugar al fenómeno de “lo planeado”, que se denominó “pop art”. Sobre todo gracias al uso (o regurgitación) de símbolos e iconos culturales que ya existían. Éstos se utilizaban al mismo tiempo para criticar a la cultura y al mundo. Fue entonces cuando el “modernismo” se convirtió en “posmodernismo” y empezó la fragmentación de las cosas. Como cualquier movimiento artístico que ha durado varias décadas, surgió para dar respuesta a grandes manifestaciones sociales y culturales que no podían pasarse por alto, como la guerra o la degradación de la humanidad en varios frentes. Es como que los artistas se dieron cuenta de todo lo que los rodeaba y sintieron la necesidad de hablar sobre ello. En este sentido, sí que hay cierta conexión con mi obra, aunque me siento más cercano a los ideales del punk y a la actitud del skate. También he intentado entender de manera extensa la historia del arte para saber como funciona. El posmodernismo tiene su origen en el arte Dada y ese es el germen de todo. Me gusta ver cómo los movimientos artísticos se solapan a los temas sociales… lamentablemente, en esa unión siempre acaban apareciendo las guerras.

Es un secreto a voces que era un gran aficionado a los Hot Rods. ¿Cuándo descubriste esta escena? ¿Podríamos afirmar que sigue siendo un movimiento DIY cercano al rock n’ roll salvaje?

Mi padre fue uno de los primeros Hot-Rodders y tenía un Ford de 1932. Durante una época fue mecánico, trabajaba bien con las manos y se encargaba de la chapa y de la pintura en la cadena de talleres Earl Scheib. Él me enseñó todas esas cosas, así que yo y mis amigos nos pusimos a reparar motores y a trabajar los capós. La cultura Low-Rider también estaba allí e interactuábamos con ellos gracias a su decoración increíble y su trabajo bien hecho. Como artista joven que era, acostumbraba a copiar las creaciones de Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. Y creo que mi obra sigue conectada a ese espíritu gracias a los clores brillantes y a los acabados delicados. ¡Supongo que nunca lo he superado! Para mí, conducir un monstruo con un motor v8 es parecido a tocar una guitarra distorsionada porque me aporta las mismas sensaciones: el sonido, la energía, las vibraciones, la velocidad y la fuerza. Estas cosas se te meten dentro y te inspiran de algún modo. Tengo un Nova de 1962 con un motor de 800 caballos con el que alucinarías.

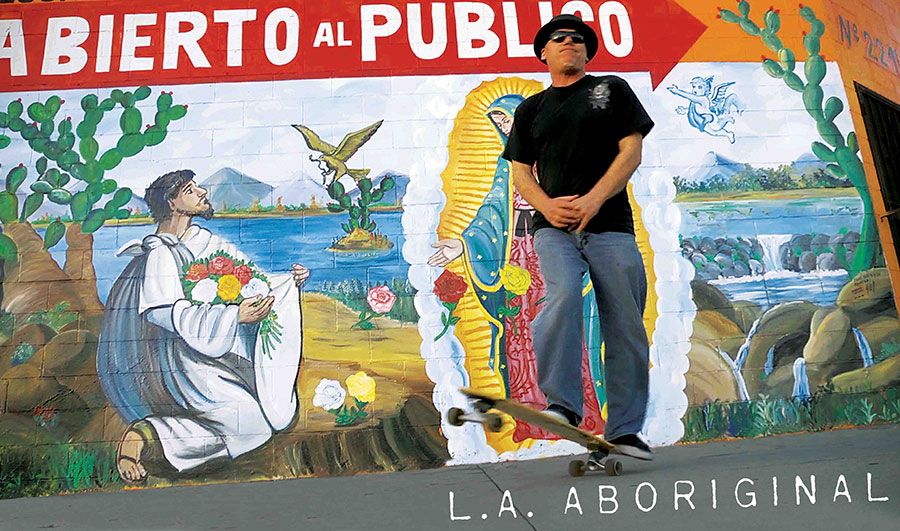

Hace unos años protagonizaste el documental “L.A. Aboriginal” y me parece un título que resume perfectamente tu carrera. ¿Crees que tu manera de abordar el arte enlaza con unas raíces culturales específicas?

Ese documental ayudó a cristalizar mi discurso como artista porque ganó varios premios en festivales internacionales y me llevó por todo el mundo, desde Australia a Nueva York pasando por Irlanda y Suecia. Creo que todos estamos influenciados por nuestro pasado y eso se expresa muy bien en el corto. El hecho de pintar como forma de arte es algo que se desarrolla poco a poco. El gran artista dadaísta Emerson Woelffer me comentó una vez que los grandes pintores están 100 años por delante de la sociedad. Eso fue una gran lección viniendo de él, un famoso pintor. Yo no añoro nada de mi pasado porque sigo haciendo la mayoría de cosas que hacía entonces, como pintar, tocar música y practicar skate. Simplemente creo que estoy empezando a entender mi pasado y cómo éste afecta a mi arte porque estoy completamente comprometido con esa cosa lenta y maleable llamada “pintura”.

En 1998 ayudaste a crear la Chouinard Foundation. ¿Por qué era tan especial esa escuela de arte y qué te llevó a iniciar este proyecto fascinante?

Sin saberlo, el hecho de comprar la casa de Nelbert Chouinard, el gran visionario de la educación artística, fue una verdadera revelación. Como estudiante de arte, recuerdo que siempre se decía que Nueva York era el único sitio donde surgían las cosas importantes y L.A se veía como un lugar vacío, donde había una cultura residual. Descubrir la historia de Chouinard me demostró lo contrario. Incluso muchos de los ideales relacionados con Nueva York empezaron gracias a Chouinard. David Alfaro Siqueiros y Hans Hoffman dieron clase en esa escuela de arte en los años 30. Stanton MacDonald Wright, el creador del movimiento “Sincromista”, también dio clases allí en aquella época. Frederick Hammersley creó el movimiento “Hard Edge” mientras daba clases en la década de los 50. En los años 60, Emerson Woelffer se convirtió en el gran maestro de gente como Mary Corse, Llyn Foulkes, Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell y muchos otros que estudiaban allí. Robert Irwin también fue estudiante en Chouinard y la totalidad de la Ferus Gallery estaba formada por artistas salidos de esa escuela. Andy Warhol enseñó sus latas de sopa Campbell allí antes de llevar el fenómeno de vuelta a Nueva York. Picasso mostró el Guernica en la Stendahl Gallery de L.A. Y, por último, el padrino del street art, mi amigo Chaz Bojorquez, también estudió allí y fue clave a la hora de popularizar el movimiento del grafiti en todo el mundo.

Este mes has creado la portada del número de septiembre de Staf Magazine. ¿Qué puedes contarnos sobre esta obra y los secretos que esconde?

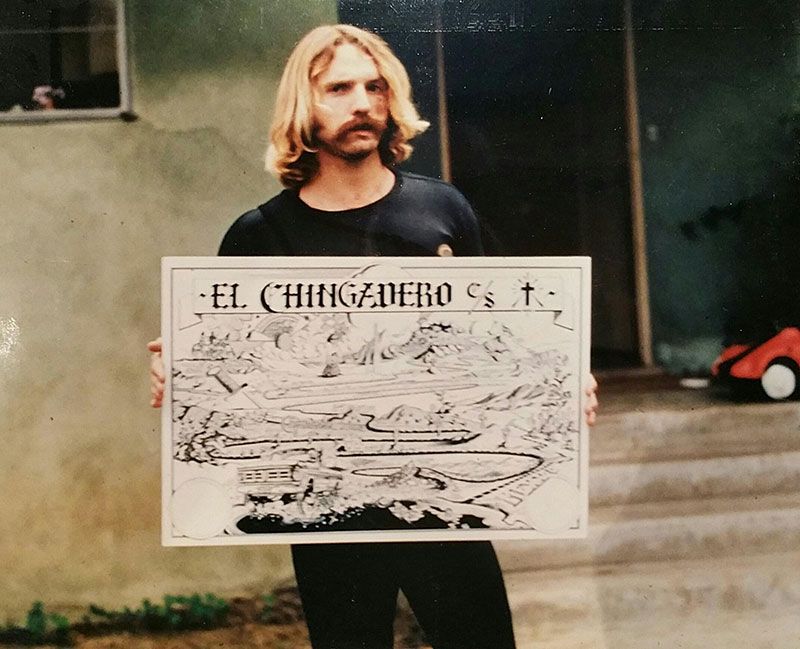

Pasé mucho tiempo pensando qué hacer y, al final, decidí crear una obra que reflejara el espíritu de la “West Coast” y estuviera relacionado con mis raíces. Como bien dices, hay muchas referencias ocultas a mis héroes y a mis amigos. Primero, la he hecho en color negro como homenaje a los dibujos en tinta que hacía de pequeño, al copiar cosas de Ed Roth, Rick Griffin, Mad Magazine o Heckle and Jeckle. También he tomado prestadas cosas de mis compañeros de California Locos, sobre todo Chaz Bojorquez y el estilo de los pósteres de John Van Hamersveld… incluso algo de Shepard Fairey. Hice cientos de bocetos durante varios meses para condensar todas estas influencias en una pieza que tuviera mi propio estilo. Y creo que lo he logrado. Por último, el fondo tiene un color crema en referencia a un póster que compré de Rick Griffin que se titula “El Chingadero” y que él hizo para anunciar la exposición de su amigo Boyd Elder en 1972. Curiosamente, también había sido alumno de Chouinard. Al final del proceso, Adam Cude me ayudó a vectorizar las imágenes y a ponerlas juntas como obra digital.

F: Boyd Elder

Para terminar la entrevista, ¿podrías avanzarnos algunos de tus proyectos inminentes y si hay planes de grabar un disco con The Savages?

¡Hay muchos proyectos en la agenda! California Locos ocupa una parte muy importante de mi trabajo y nuestra colaboración con la “House of Rodney Mullen”, Dwindle Distribution y la marca Dusters California de Nano Nobrega con una colección de tablas de skate con nuestras obras ha sido muy emocionante. Además, nos ha abierto las puertas del mercado internacional, desde Europa hasta Asia. Justo acabamos de terminar nuestras dos exposiciones en ambas costas, que nos han llevado de Venice Beach a Virginia Beach. También organizo mis propias exposiciones como artista independiente. Y en referencia a Los Savages, hay muchas novedades. Esperamos seguir desarrollando nuestro sonido poco habitual, nos gustaría grabar un álbum con en gran Llyn Foulkes e intentar cerrar una gira para el 2017. Tocar con músicos como Ian Espinoza, Bryan Head, Jim Grinta y Toby Holmes es la culminación de todo lo que he hecho en el mundo de la música. Son realmente buenos y logramos sacar lo mejor de cada uno de nosotros… sé que ellos sacan lo mejor de mí y me siento afortunado de formar parte de esta banda.

L.A. Aboriginal

English:

DAVE TOURJÉ.

THE ORIGINS OF THE REVOLUTION.

Let’s start this story from the beginning: how was it growing up in northeast L.A. as a teenager in the 70’s? How was life in your neighbourhood?

Northeast L.A. was an extremely fertile place to grow up for many reasons. It was a place where the working-class White and Mexican cultures converged. This caused tension, but also integration of ethos. In my case, my mother was from Mexico City, so I straddled both sides of the line in some ways. In NELA, there was a strong hotrod culture. motocross pioneers lived there like the LeBlanc and Burns families, BMX when they began to cut the 2 Freeway in during the late ‘60s. There were the gang elements – Los Avenues, but also smaller gangs, some white, like the Delevan Boys. There was a strong ski culture, as back then, we always got a lot of snow in the local mountains. Though inland, there was a great surf culture. And finally, skateboarding and snowboarding in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and the punk rock scene. Bands like The Gears, X, Top Jjmmy and The Rhythm Pigs lived around, as well as the Hully Gully studio nearby, where everyone from Los Lobos, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction and all the bands rehearsed. I helped build it with my friend, the owner Bill Mentzer. I was involved in all of the above, one way or another.

One of your early art influences was Diego Rivera. How did you discover his murals and what was the impact on you?

Early in my life, my mom took my sisters and I to live with our grandmother in Mexico City. Every day we would walk to Chapultepec Park or around the city to play or look at art. It was at the central library that I was confronted by the large Rivera mural. I would just stare at that work and I saw the narrative of struggle in it. Strife, pain, and revolution… these were things that became real to me from looking at this work. Because I was alone there, I would use drawing as a way to occupy my time. I connected the two ideas (art and revolution) there and knew I had to at least attempt to become part of the narrative, not just a spectator in the world.

What do you remember about the beginnings of skate in L.A? Did you meet the Dogtown boys? I have read that you went to a spot called “The Bowl”…

I began skateboarding in 1967 as a 7 year old. My dad bought me a “Black Knight” board with clay wheels for my 7th birthday. My aunt and uncle owned a beach house in Newport Beach and everything changed around 1972. I was there at Hanifin Surfboards in Newport when the first Cadillac wheels arrived. Pat Hanifin pulled them out of a box and said: “Kid, get your mom to buy these for you.” So I did. This was before skate mags or advertising. I put them on my board and could not believe the smoothness and speed. Back home, I lived in the hills of N.E.L.A, an area called Highland Park and Mount Washington. Here we had steep, freshly paved streets that now we could learn to shred on. We found a drainage ditch we called “The Bowl” that we eventually learned to ride. Once in a while, some of the Z-Boys would show up. I remember skating there with Stacey Peralta and Shogo Kubo. The Bowl was a local “secret spot”, small but intense and extremely challenging. It all became a daily obsession for years, and when the drought hit and emptied the pools, the revolution was on!!

You were also involved in the early punk scene in L.A. Do you think that movement started as an opposition to previous music / culture scenes? What do you think has been its legacy? And nowadays you are also a huge blues music enthusiast…

The film “The decline of western civilization” by Penelope Spheeris tells the story well. There was so much going on in the scene; it was absolute creative chaos. The L.A punk scene was not just “punk rock”. It was everything: punk rock, country, blues, folk and noise, you name it. There was X, Top Jimmy and The Rhythm Pigs, Black Flag, The Plugz, SST Records and the list goes on and on. In retrospect, it was an American uprising, borrowing from everything. To this day, the scene has had monumental influence and in my mind it has never been repeated anywhere. Personally, I think many of us just had enough of disco and spandex hair bands. It became working class, where a punk-ass auto mechanic could plug in a cheap guitar and basically say “fuck this!!!!!!”

You studied at the Art Center College of Design and also at the University of California. How do you remember those days as a student? Did you learn something useful for your future career?

University “art education” was enormously helpful in learning what I did NOT want. Sitting in Art Center’s Saturday high school class in 1977, I learned I did not want to go into “advertising design” and I learned some figure drawing, which helped me draw my visions. At UCSB, I saw the politics of art education, I hated it and quit artschool to play music in L.A after 2 years of that, in 1980. I was disillusioned by “art education” and never touched a pencil again for 5 years. My art education was so good as a child at home with supportive parents, and in grammar school and high school as a teenager. It was very supportive. I already had the chops before college, and university was detrimental to the creative spirit as I saw it and my way out was to quit and leave my scholarship behind. I think this saved me as an artist and I think I am the only practicing artist from my university experience still making art. Though I have no degree, I got much more out of a sign painting program at the West Valley Occupational Center a couple years later. I think that’s what I do now: make signs, albeit in the ‘fine art” realm.

Your artwork has been praised for “the violence of colors” and also “the culture of symbols.” What is your aim when working on a piece? Do you feel connected to pop art in some way?

I think I’m connected to “pop art” in a way. The postmodern shift that occurred around 1960 was that the existential notion of the “unplanned” gestural impulse gave way to the “planned” phenomenon known as “Pop” art, with the regurgitated use of existing cultural symbols and icons. These were turned inward on the culture in order to critique the culture and the world at large. This is where “modernism” became “postmodernism” and began its continuously fragmenting orbit. Like any lasting art movement, it was in response to heavy social and cultural manifestations, which can not be avoided, like war and the degradation of humanity in various ways. Sort of like the artist noticed that Rome was burning, and was forced to talk about it. In that sense, there is a connection, I guess. But I feel much more connected to more contemporary ideas like punk rock ideals and the attitude of skateboarding. I also have tried to understand wider fine art history, so as to understand how art lineage works. All this postmodernism goes back to Dada. That is the crux of it. I like to understand art movements overlaying social issues and, unfortunately, there you generally find – war.

It is not a secret that you are a huge Hot Rod enthusiast as well. When did you discover this scene? What can you tell about your cars? Is it still a DIY movement connected to rock music?

My dad was an early Hotrodder. He had a ’32 Ford he bumped out. He was a mechanic for a while, good with his hands, and worked as a body and paint man at Earl Scheib. He taught me all of that stuff and my friends and I would rebuild engines, do our own body work, etc. Lowrider culture was also there and we would interact with them as well, with their incredible paint and pinstripe work. As a young artist, I would copy Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s monsters and street rods. My work is all somehow still connected to this: the bright colors and slick finishes. I never got over it. To me, revving up a monster V8 is very similar to playing a loud guitar chord, because it rocks my boat the same way. The sound, energy, vibration, speed and power, these things stir you from the inside and for me provide inspiration somehow. I own an 800 horsepower blown ’62 Nova pro street that would blow your mind.

A few years ago you starred in a documentary called “L.A. Aboriginal” and I really enjoy this title. Do you think your approach to art is aimed to keep a certain local art tradition alive? Do you miss something from the past?

“L.A. Aboriginal” really crystallized things for me as my statement. At the time it was made, the huge Getty-funded Pacific Standard Time was in full swing. I got a show in Beverly Hills and it occurred to me that this big celebration of “L.A. Artists” ended in 1980, and was composed of mainly artists who were not from L.A. I made a stand for being a native (i.e. “aboriginal”) for me and my friends in the same boat – and that’s how the California Locos was born. As a short film winning awards, it took me around the world, from Australia to New York to Ireland and Sweden and beyond. I think we are all influenced by our past, which is expressed in the film. Painting, as an art form, develops slowly I think. The great abstract Dadaist Emerson Woelffer told me that a great painter is 100 years ahead of society. That was pretty sobering to hear, coming from him, a truly great painter. For me, I don’t miss anything from my past, because I still do most of it like making art, playing music and skateboarding. I think I am just finally getting around to understanding my past more and how it affects my art, being fully committed to that incredibly slow, evolving process called “painting”.

In 1998 you helped to form the Chouinard Foundation. What was the magic of that school back in the day? Why did you decide to get involved in that project?

Unknowingly buying the home of Nelbert Chouinard, the great art-education visionary, was a revelation to me. As an art student, the diatribe was always that New York was the only place that important art came from. L.A. was viewed as a hollow, provincial cultural backwater. Discovering Chouinard proved otherwise in a huge way. In fact, most of the “New York” ideals began with Chouinard, one way or another. David Alfaro Siqueiros and Hans Hoffman taught there in the ‘30s. Stanton MacDonald Wright invented “Synchromism” while teaching there in the ‘30s as well. Frederick Hammersley launched the “Hard Edge” movement while teaching there in the ‘50s. In the ‘60s, Emerson Woelffer became the great teacher of the likes of Mary Corse, Llyn Foulkes, Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell and many others who went there. Robert Irwin was a student and teacher there. The entirety of the Ferus Gallery was composed of Chouinard artists. Andy Warhol showed his soup cans there before taking his movement back to New York. Picasso showed “Guernica” first at the Stendahl Gallery in L.A and don’t forget the great “NY” artist Jackson Pollock was actually an “L.A.” artist because he grew up here and went to Manual Arts high school!! Lastly, the “godfather” of graffiti Chaz Bojorquez went there and helped launch the global graffiti movement.

This month you have created the cover art for Staf Magazine’s new issue. What can you tell us about this piece? Are there any “secrets” hidden in it?

I spent a lot of time thinking about what to do. I settled on the idea of creating a very “West Coast” statement tied to my roots. It has many buried references to my heroes and associates. First, it is rendered in black as a reference to the ink drawings I grew up copying from Ed Roth, Rick Griffin, Mad Magazine, Heckle and Jeckle, etc. I borrowed from my California Locos associates Chaz Bojórquez and the poster style of John Van Hamersveld, as well as Shepard Fairey. I made hundreds of drawings over several months in order to distill all this influence into one communication that I feel is my own style, within that context, and I am happy I think I succeeded. In the end, I even made the background a cream color in reference to a Rick Griffin poster I bought called “El Chingadero” he did for his friend, another Chouinard artist named Boyd Elder for his show in 1972. In the end, Adam Cude vectorized all my drawings and helped pull it all together as a digital work.

In order to finish the interview, what are your future projects as an artist and as a musician? Any plans to record with the savages?

Wow, so many projects!! The California Locos is an important project for me and my guys: Chaz Bojórquez, John Van Hamersveld, Norton Wisdom and Gary Wong. Our collaboration with the “house of Rodney Mullen”, Dwindle Distribution and Nano Nobrega’s Dusters California for the Locos line of skateboards is super exciting, and bringing us international opportunities from Europe and Asia. We just wrapped up our bicoastal California Locos 2016 that took us from Venice Beach to Virginia Beach. In addition, I always have my own shows and opportunities as an independent artist, which are always cooking as well. For my band, Los Savages, we have many things happening. We hope to continue growing our unusual sound. We contemplate making a record with the great Llyn Foulkes, and intend to keep pushing the limits and possibly tour in 2017. To play with these musicians – Ian Espinoza, Bryan Head, Jim Grinta and Toby Holmes and Dave Ryan, is a culmination of all I have done in music. They are so great at what they do, and I think we bring out the best in each other – I know they bring out the best in me and I am just lucky to be part of this great band.

www.californialocos.com

www.davetourje.com