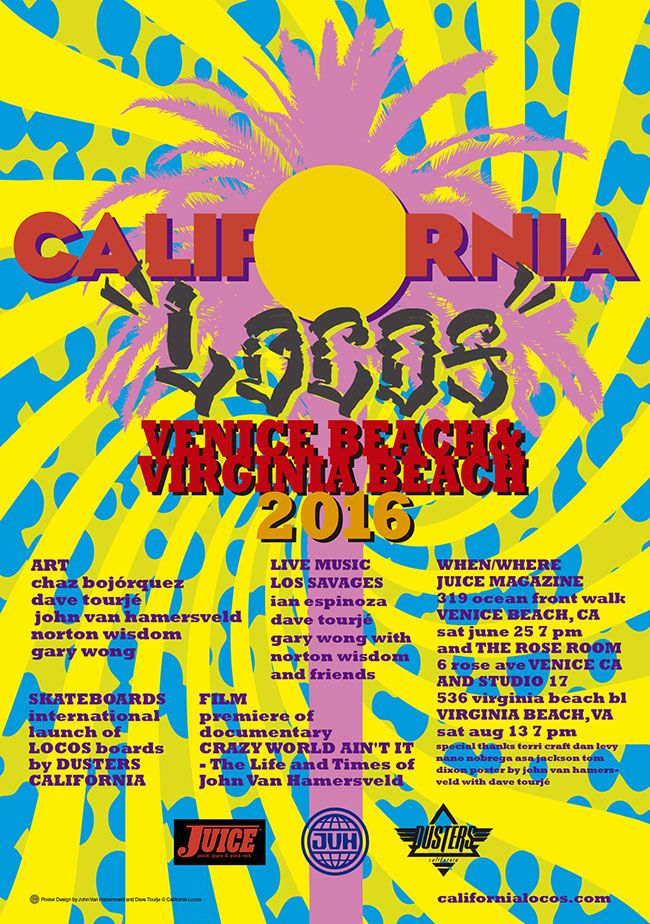

{english below} Hemos entrevistado a CALIFORNIA LOCOS, el influyente colectivo de artistas de Los Ángeles mientras preparan sus exposiciones de verano en ambas costas de Norteamérica. Estos dos eventos están patrocinados por JUICE MAGAZINE y DUSTERS CALIFORNIA, además, también incluyen nuevas obras de cada artista y el lanzamiento de una colección de tablas de skate personalizada por los LOCOS gracias a su colaboración con la marca DUSTERS. Asimismo, se estrenará el documental “CRAZY WORLD AIN’T IT – The Life and Times of John Van Hamersveld” y la música en directo la pondrán Los Savages, un grupo formado por Ian Espinoza, Dave Tourje, Gary Wong and Norton Wisdom.

Toda revolución tiene un inicio, aunque muchas veces los caminos que llevan a ella son indescriptibles. Sin embargo, los orígenes de la cultura alternativa de California están ampliamente documentados y se remontan a la década de los 50 del siglo pasado, cuando los jóvenes rompieron definitivamente con la moral conservadora de sus padres y se dejaron llevar por todos los placeres sensoriales y creativos que había popularizado la escena beat. Fue en aquel ambiente de experimentación autóctono de la Costa Oeste donde Chaz Bojorquez se convirtió en el padrino del grafiti, Norton Wisdom se alzó como pionero de la pintura de performance, Gary Wong se posicionó como leyenda underground en varios frentes (sobre todo el blues), Dave Tourje se consolidó como artista visual arraigado al punk y John Van Hamersveld triunfó en el mundo del diseño aplicado al surf y al rock. Todos ellos cambiaron su entorno gracias a una creatividad desbordante, pero nunca imaginaron que sus obras tendrían una repercusión internacional cuando la escena alternativa dio el salto al mainstream y las grandes marcas se dejaron seducir por la transgresión del los “outsiders”. Como es evidente, las modas avanzan en ciclos y actualmente se ha redefinido el concepto de escena alternativa. Sin embargo, estos cinco personajes siguen al pie del cañón con sus trabajos a contracorriente y han decidido formar un colectivo llamado “California Locos” para reivindicar su estatus, después de tantos años de carrera. Aprovechando que están preparando una espectacular exposición colectiva en Venice Beach para el verano y que han diseñado una colección exclusiva de tablas de skate para la marca Dusters California, hemos tenido la oportunidad de entrevistar conjuntamente a Chaz, Norton, Gary, Dave y John para conocer su apasionante historia y sumergirnos en las entrañas de una escena que cambió el mundo desde la playa y el asfalto. Todo lo demás son anécdotas que se llevan las olas a ritmo de rock n’ roll.

Dave Tourje

Remontémonos a los inicios de vuestra apasionante historia. ¿Cómo empezasteis a trabajar como un colectivo y cuál es la motivación detrás del proyecto “California Locos”?

(Dave): A lo largo de los años, todos nosotros nos hemos ido cruzando en las escenas contraculturales de Los Ángeles, empezando por el surf y el skate, hasta llegar al punk y al arte. Aunque nada cristalizó hasta el 2011, coincidiendo con mi exposición titulada “L.A. Aboriginal”, que me pidieron que organizara una mesa redonda. Automáticamente invité a estos buenos amigos artistas porque compartimos cierta armonía en temas estéticos, a pesar de ser muy diversos. Fue entonces cuando nacieron los “California Locos” como entidad propia y esto ha seguido funcionando y creciendo sin parar. Pero me gusta pensar que el inicio real viene de más lejos porque cada uno de nosotros comparte unas experiencias y ha vivido un fragmento distinto de la realidad de las subculturas de Los Ángeles. A pesar de que el concepto “multicultural” ha existido y ha gozado de éxito en L.A. durante mucho tiempo, es ahora que se está viviendo a lo grande en todas partes. Tal vez este sea el motivo por el cual “California Locos” tiene una conexión tan amplia. Se trata de “cada uno de nosotros” en lugar de “nosotros”. En este sentido, la mejor manera de explicar esta amalgama de ideas es el logo, porque combina la palabra “California” diseñada por John Van Hamersveld y la palabra “Locos” creada por Chaz. Nuestra idea no es decir que estamos locos como algo negativo, sino que estamos locos por nuestro arte, por la vida y por la creatividad

Una de las primeras cosas en las que pensamos al hablar de California es el surf. ¿Cómo describirías la influencia de la cultura de playa en tu vida y en tu arte?

(John): El condado de L.A. está dividido en 55 ciudades que piensan completamente distinto en referencia a las demás. Yo practiqué surf en South Bay, Huntington Beach, Malibú, La Jolla y Santa Bárbara. Cada una estaba poblada por distintos chavales con ideas opuestas sobre el surf, pero compartíamos ese paisaje del sur de California. Yo me juntaba con ellos para coger olas, pero también esquiaba con el surfer Dewey Webber en las montañas cercanas y también en Mammoth Mountain. En 1961, cuando me fui de Palos Verdes para empezar en la escuela de arte del downtown de L.A, eso fue el fin de la cultura del surf para mí. Aunque el póster de “The Endless Summer” llegó a Nueva York en 1966 y se convirtió en un éxito entre la gente que no practicaba surf. Entonces se agotó en todo el mundo como imagen icónica del sur de California. Irónicamente, ese cartel se convirtió en un símbolo cultural mientras yo trabajaba en Hollywood… que a su vez era un lugar internacional y distinto del resto. El mundo entero está influenciado por lo que sucede en el sur de California, pero Nueva York odia lo que allí sucede y los medios de comunicación nos presentan como unos personajes salidos de una película de animación de Disney que viven una vida muy deportiva. En 1980 me trasladé de Hollywood a Malibú y empecé a practicar otra vez surf. Volví a dejarlo en 1991 por culpa de la masificación de las playas y de la contaminación del océano. El surf se ha transformado en una moda y no en lo que yo conocí.

Norton Wisdom

Actualmente, el grafiti es una disciplina artística que tanto se puede encontrar en calles como en museos. ¿Cómo lo recuerdas en la década de los 70 en Los Ángeles y por qué te apasionaba?

(Chaz): Ten en cuenta que ya había grafitis en Los Ángeles en la década de los 50. La historia de este arte empezó con las revueltas raciales que protagonizaron los jóvenes mexicanos que vivían en Norteamérica contra los marines norteamericanos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. En los barrios latinos, los jóvenes se unieron y, poco a poco, formaron bandas para proteger a su comunidad de los “outsiders”. Gracias a este ambiente social, las bandas desarrollaron su propia manera de hablar y su estilo de vestir. Empezaron a reclamar las calles como suyas mediante pintadas con sus nombres en las paredes, utilizando un bote de pintura y una brocha. En los años 50 se vendió el primer espray de pintura en una tienda y los grafitis se expandieron con letras mucho más trabajadas. En aquella época yo era un crío y vi por primera vez aquel arte. Me encantaba mirarlo. Durante años practiqué en papel y no hice mi primer tag en la calle hasta 1969. Recuerdo que pintaba en el lecho del río de L.A. donde las paredes de cemento se extendían durante millas. Hacer ese tipo de arte y pintar grafitis era lo más excitante que podía hacer cuando era joven. El grafiti siempre fue un viaje personal porque no buscaba fama ni dinero. Era un reto personal que consistía en seguir un camino y dejar que el arte me arrastrara.

Desde 1979 has colaborado con diversos grupos de música para hacer performances de pintura en directo. ¿Existe una conexión evidente entre arte y rock n’ roll?

(Norton): Las membranas que separan distintas disciplinas, como la pintura y la música, son muy porosas si el artista tiene algo que decir. Por ejemplo, reflejar la belleza y la libertad de la raza humana. Pero si el artista no tiene nada que contar, la pared que separa estos dos mundos es infranqueable y nunca se encuentra el equilibrio. Desde finales de los años 70, no he conocido a ningún músico que no haya considerado mi pintura como una parte intrínseca de su actuación… y todos han pensado que la actuación estaría incompleta sin la aportación de mi arte. Cuando la banda Panic empezó a actuar en los clubes de punk a principios de los años 80, nunca me miraron como un tipo raro. Una banda con un pintor era algo aceptable. Entonces la escena punk evolucionó por los caminos habituales que abre el gran público. Los comisarios de los museos y los promotores de conciertos dejaron de ser relevantes. No eran más que marionetas en manos del mercado y de los políticos. Sin embargo, hoy vuelven a tener el control y tienen sus manos puestas el grifo de la cultura.

John Van Hamersveld

Tengo entendido que, en lugar de nacer en el Delta del Mississippi, creciste en el barrio de South Central de Los Ángeles y en los años 60 te enamoraste de un género tan negro como el blues…

(Gary): El barrio de Eastside tenía mucha vida y era muy rico gracias a su mezcla de culturas y de influencias musicales. Más tarde, mis padres se trasladaron al barrio de Westside, cerca de La Ciénaga Boulevard, y yo empecé a ir a un instituto frecuentado por familias de clase media trabajadora… algo totalmente opuesto a lo que veía en mi anterior barrio. Fue una diferencia que me impactó mucho porque las proporciones de razas habían cambiado. Nunca antes había estado en compañía de tantos blancos y judíos. Me llevó un año acostumbrarme a ese cambio. A finales de los años 50 y principios de los 60, debido a la nueva clase media, el barrio de Westside vio aparecer muchos clubes y bares con música en directo, sobre todo jazz, y los locales más pequeños programaban conciertos de grupos con órgano. Pasé muchas noches de mi época de estudiante en esos antros, viendo a algunos de los gigantes del jazz tocando la música más “hip” del mundo: John Coltrane, Art Blakley and The Jazz Messengers, Charlie Mingus en el The It Club, Cannonball Adderley en The Metro, Miles Davis Quintet en The Adams West, aunque también pude ver a Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, Little Milton, B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, Big Mama Thornton, Lowell Fulson y muchos más de aquella época. Gran parte de mi educación musical fue entender que el jazz, una forma de arte original americana, provenía del blues con sus raíces profundas en la historia de Norteamérica. En 1964 me encerraron en la cárcel después de participar en un acto de desobediencia civil. En aquella época llevaba siempre una Bb Hohner Marine Band en el bolsillo trasero de los pantalones. Por alguna razón seguía teniendo esa armónica a pesar de estar arrestado. Después de moverme por varias cárceles, llegué a una celda al lado de un hombre negro que también tenía una Bb Marine Band. Vaya casualidad. Yo la había guardado durante meses en mi bolsillo y ahora me cruzaba con un completo extraño que tenía una idéntica. No dudé en preguntarle: “¿Dónde está el blues?” Él me miró fijamente y sólo dijo: “Entre los agujeros 1 y 3”. Al día siguiente me mandaron a otra cárcel y nunca más vi a ese tipo, aunque ya había tenido mi primera clase de armónica de blues. Entonces toqué y toqué hasta que encontré la Blue Note. Ése fue el inicio de mi aventura en el mundo del blues, donde todavía me encuentro actualmente y en el que me he ganado cierto respeto por parte de mis compañeros.

Gary Wong

Asimismo, tú creciste en el Northeast de Los Ángeles en los años 70 y te involucraste en la escena punk. ¿Qué recuerdas de aquella época en la que la música tenía una carga política?

(Dave): La escena punk de L.A. de finales de los años 70 y principios de los 80 era extremadamente ecléctica. No se trataba solamente de punk, aunque parecía que todo sucediera bajo ese nombre. Era un movimiento muy vivo e incluso sigue inspirando cosas en la actualidad. Era una escena que tenía en cuenta la multiculturalidad, con bandas como X, Los Plugz, Top Jimmy and The Rhythm Pigs y Black Flag, que tenían muchos puntos en común. Yo trabajé para Bill Mentzer, que fundó los Hully Gully Studios, y lo ayudé a construirlos en 1980, muy cerca de NELA y del L.A. River. Allí ensayaban todas las bandas que tuvieron repercusión en la escena. Fue algo que tuvo éxito y después de varios años se desgastó, aunque nunca hemos podido olvidarlo. The Dissidents nos formamos en 1983 y llevamos la imagen de eclécticos hasta el límite, mezclando punk, funk, metal, jazz vanguardista, reggae… también nos quemamos, sin embargo, dejamos una huella en bandas posteriores.

¿Cómo explicarías la influencia del movimiento por los derechos civiles en los años 60 y 70 desde el punto de vista de un surfer?

(John): Yo crecí en una comunidad predominantemente blanca, donde vivían familias de origen alemán, holandés, judío y británico, pero me consideraba un chaval de los años 50 y que además era surfer en Palos Verdes. El Segundo High School solamente tenía un alumno negro y una chica asiática. Sin embargo, la raza no tenía nada que ver con el color de la piel… de hecho, yo era tan blanco, que mis colegas me llamaban “El Reflector” cuando llegaba el verano. Recuerdo estar en un spot llamado Boomer en La Jolla y había un chico negro que practicaba bodysurf hablando con nosotros, era algo distinto. Con 19 años me matriculé a la escuela de arte y éramos una clase internacional. Después fui al Chouinard Art Institute, que estaba cerca del downtown, y eso era un ambiente multicultural. A finales de los años 60 y principios de los 70, cenaba cada noche en un lugar llamado Little Tokyo. Pero el alquiler de mi estudio en Kingsley también incluía un jardinero japonés. En la década de los 90, conocí a Chris Blackwell, que era jamaicano, fundó Island Records y entró como socio de la cadena Fatburger Restaurant. Sus socios financieros eran afroamericanos y yo me encargué de diseñar la imagen, además de trabajar estrechamente con dos ejecutivos negros durante cinco años en los que aprendí mucho sobre como funciona el mundo. No se trataba únicamente de vender hamburguesas, sino que se trataba de romper prejuicios y vender hamburguesas hechas por afroamericanos a todo el mundo. Hoy, esta cadena tiene restaurantes en 137 ciudades, incluyendo Dubái y Beijing. Trabajando en Hollywood aprendes que todo el mundo mira películas, así que la comunicación actual tiene que ser internacional y, por suerte, tenemos Google en el bolsillo.

Chaz Bojorquez

¿Cómo fue realmente la primera exposición de California Locos en Los Ángeles?

(Chaz): Podríamos decir que el colectivo “California Locos” se ha ido fraguando en los últimos 50 años y algunos de nosotros hemos expuesto conjuntamente con anterioridad. Cada uno representa una mirada distinta del estilo de vida californiano y aporta una gran tradición artística. En nuestra primera exposición en L.A. llevamos esa tradición a la galería de arte y dejamos que los espectadores disfrutaran de cada uno de nosotros. Aunque se dieron cuenta de los puntos de unión de nuestro trabajo. A través del skate, del punk, del surf, de la música, de las performances y del grafiti, nosotros reflejamos una experiencia contemporánea y madura… nuestro éxito viene de nuestros logros pasados y de los hitos que conseguimos. Como embajadores veteranos del arte, afrontamos “California Locos” con un mensaje, una voz y un sentimiento que se aprecian en todos los rincones del mundo. Sin embargo, esto sólo podía surgir en un lugar como el sur de California. Y ha sido un honor.

¿Cuándo crees que la cultura alternativa empezó a dar un giro hacia el mainstream? Puede que fuera a mediados de los años 80 a causa del éxito de la MTV…

(Norton): Una de las plataformas más importantes que sirvió para acercar la energía alternativa del punk al público masivo fue el New Wave Theater. Un programa gratuito de televisión por cable en Los Ángeles que presentaba Peter Ivors. Los mejores profesionales de cámara, luces y sonido de la industria aportaban su talento sin cobrar para producir ese programa sobre la escena underground de mediados de los años 80. Los grandes empresarios que querían recuperar el control del mensaje aplastaron ese programa y la MTV fue su martillo. Invirtieron millones en los videoclips de las grandes bandas, que no tenían nada que decir sobre el mundo real. La MTV filtró el contenido de los mensajes y los hizo políticamente correctos. Esto obligó a los músicos y a los artistas auténticos a volver a una escena alternativa y undergound, que todavía tiene fuerza. A este lado del mercado encuentras a gente que tiene cosas que decir, sin importar el medio de difusión.

Chaz Bojorquez

¿Qué recuerdos tienes de tus años en la Chouinard Art Scool de Los Ángeles?

(Gary): Los mejores estudiantes de arte de los Estados Unidos y del resto del mundo estaban allí, sobre todo en artes aplicadas: animación, diseño, moda, cerámica, fotografía e ilustración. También en bellas artes: pintura, dibujo, grabado y escultura. Fue en este segundo grupo donde, en mi tercer curso, decidí que tenía que centrarme. En ese ambiente, los estudiantes tenían libertad para moverse entre disciplinas y establecer puentes con otra gente. La creatividad era un bien muy apreciado y crear algo de la nada era una necesidad. Todos los profesores en los cursos avanzados eran muy activos en sus respectivas materias y aportaban un diálogo contemporáneo en las clases. El valor del tiempo que pasé en esta escuela es imposible de medir porque ha tenido un efecto enorme en mi carrera. No soy una persona que se implique en política, simplemente me rijo por las cosas que me emocionan y que me incitan a contar una historia visual, combinando imágenes aparentemente dispares para que tengan un resultado interesante. La recompensa por mi esfuerzo es saber cómo los demás interpretan lo que sienten al ver mis obras, ya sea con un significado político o de otra clase. Pero, sobre todo, pinto para mí mismo. Por amor al arte, aunque he aprendido que, como artista, es importante tener en cuenta al público.

Información sobre las exposiciones:

VENICE BEACH, CA

Juice Magazine (319 Ocean Front Walk, Venice, CA 90291)

The Rose Room (6 Rose Ave, Venice, CA 90291)

Fechas: del sábado 25 de junio (inauguración 19:00h) al sábado 2 de julio.

VIRGINIA BEACH, VA

Studio 17 (536 Virginia Beach Blvd, Virginia Beach, VA 23451)

Fechas: del miércoles 13 de agosto (inauguración 19:00h) al miércoles 20 de agosto.

Para más información:

www.californialocos.com

FACEBOOK

Chaz Bojorquez

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

Norton Wisdom

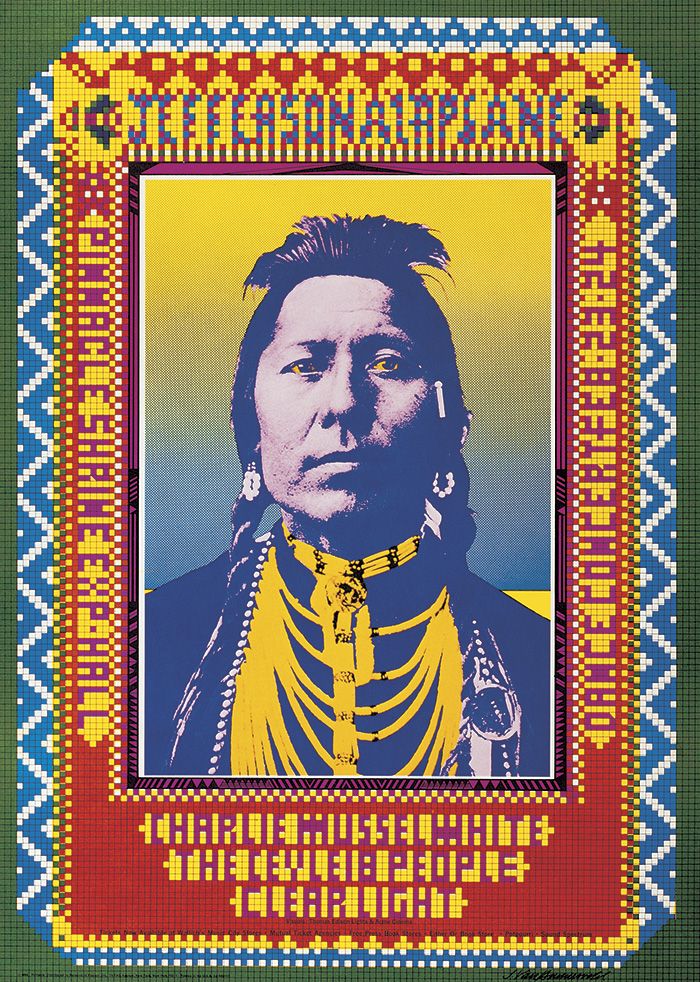

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

John Van Hamersveld

Gary Wong

Gary Wong

Gary Wong

Gary Wong

Gary Wong

Gary Wong

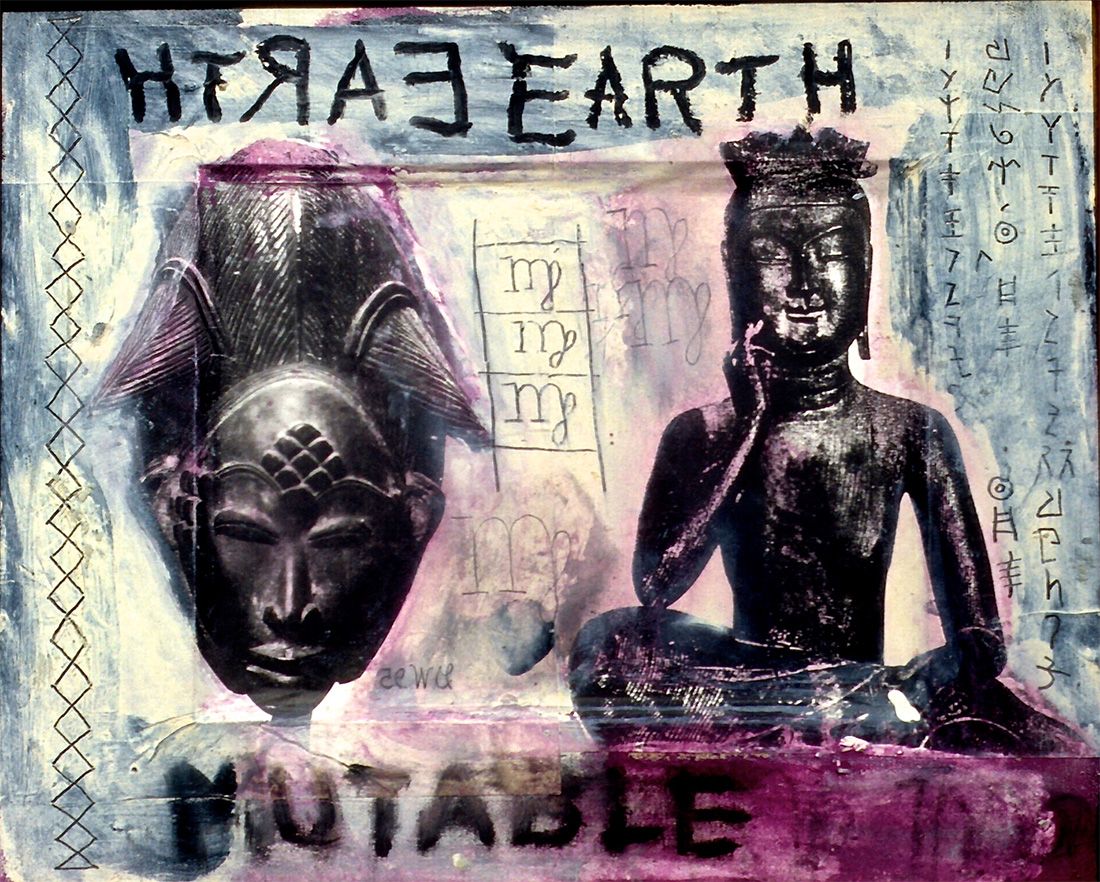

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Dave Tourje

Chaz Bojorquez

Chaz Bojorquez

Chaz Bojorquez

Chaz Bojorquez

Chaz Bojorquez

English:

CALIFORNIA LOCOS.

REVOLUTION PIONEERS

We interviewed the influential Los Angeles art collective CALIFORNIA LOCOS as they prepare for their 2016 bicoastal summer events. These events are sponsored by JUICE MAGAZINE and DUSTERS CALIFORNIA and include new artworks from each artist, the international launch of the LOCOS skateboard line by DUSTERS, a preview screening of the film “CRAZY WORLD AIN’T IT – The Life and Times of John Van Hamersveld,” and live music by Los Savages featuring Ian Espinoza, Dave Tourje, Gary Wong and Norton Wisdom.

Every revolution has a beginning, and the paths that lead to it are often indescribable. However, the origins of the alternative culture in California have been widely documented. They go back to the 50s, when the youngsters broke out of the conservative moral of their parents and were carried along with the sensorial and creative pleasures that became popular with the beat scene. It was in that experimental environment from the West Coast where Chaz Bojorquez became the godfather of graffiti; Norton Wisdom became a pioneer in live paintings; Gary Wong rose as an underground legend in several (specially in blues); Dave Tourje consolidated himself as a visual artist rooted in punk; and John Van Hamersveld succeeded in the design world applied to the surf and rock cultures. They all changed their environment thanks to their boundless creativity, but they never imagined that their works would have international repercussion as the alternative scene became mainstream and the big brands got seduced by the transgression of the “outsiders”. It is obvious that fashion trends go in cycles, and currently the concept of alternative scene has been redefined. However, these five characters are still ready for action with works that swim against the current. They have recently founded a collective named “California Locos”, in order to reclaim their status after such long careers. We had the chance to interview Chaz, Norton, Gary, Dave and John together to learn more about their fascinating story and be able to immerse ourselves in the core of a scene that changed everything from the beach and the pavement. The rest are only anecdotes dragged by the waves. The LOCOS present two bicoastal events, one opening in Venice Beach on June 25th, and one in Virginia Beach on August 13th.

How did you all five start working as a collective and what was the aim behind this amazing project called “California Locos”? Did you all know each other before?

(Dave): Over the years, we all crossed paths loosely in the Los Angeles counterculture scenes, beginning with surf and skate, punk rock, art, etc. But it all did not crystallize as a movement until 2011 when, during my show in Beverly Hills called “L.A. Aboriginal”, I was asked to create a panel discussion. I automatically invited these artists/friends of mine due to our harmony of aesthetic realities, diverse as they are. It was here that the “California Locos” was born as a unified communication, which has been going and expanding ever since. The actual birth of it comes long before, because each one of us shares an experience, a different slice of Los Angeles subcultural reality. Though “multi culture” has been alive and well in LA for a long time, it is now, more and more, occurring in this world at large. Perhaps that’s why the “California Locos” has such a broad connection. It is more about “everyone” than it is about “us”. The logo combines the word “California” done by John Van Hamersveld and “Locos” by Chaz, which expresses the amalgam best. Our notion is not that we are “crazy” as insane, but that we are crazy about our art, life and creativity.

One of the first things that everybody thinks when talking about California is surfing. How would you describe the influence of this beach culture in your life and your art?

(John): The cities of LA County are divided up into 55 cities that all think differently about each other. I surfed the South Bay, Huntington Beach, Malibu, La Jolla, and Santa Barbara. Each had different kids with different ideas about surfing in the Southern California landscape. I’d surf with them, but I also skied with Dewey Webber the surfer in the local mountains and Mammoth Mountain. When I left Palos Verdes at 19 years old in 1961 for Art School in downtown LA, that was the end of surf culture for me, though the “Endless Summer” poster went to NYC in 1966 and it was a hit to non-surfer and sold out all over the world as the image of Southern California. So the poster became a cultural sign ironically, while I was working in Hollywood, which was international and different from Southern California. The whole world is influenced by Southern California, but NYC hates California and the media make us out to be a Disney like cartoon of ourselves in a stupid sporting life. In 1980 I returned from Hollywood to Malibu and started surfing again. Out of that return of the ocean society I designed a surf lifestyle image of Malibu as place in surf culture made a campaign for Jimmy’Z, and restarted the Endless Summer image with Bruce Brown. I dropped out again in 1991, ending surfing because of the crowds and polluted ocean. Surfing had become a fashion statement, not surfing.

Nowadays graffiti is a very popular art form that we can find in museums and galleries. How was it back in the 70’s in LA and what did you enjoy the most about it in order to devote your life to it?

(Chaz): There was graffiti in Los Angeles since the 50’s. Our graffiti history started with the race riots between the Mexican-American youth and the Anglo U.S. Navy sailors during WWII. Inside the Latino neighbourhoods, the young men united and slowly formed the gangs to protect the community from outsiders. Out of this social environment the gangs developed their own forms of speech and dress styles. They started to claim the streets as their own by painting their names on the walls with a bucket of paint and a brush. In the 1950’s the first spray can was sold to the public and the graffiti on the walls got bigger and more stylized letters. That was the time as a child I first saw graffiti and loved looking at it. I practiced on paper for years and painted my first street tag in 1969. I would paint in the L.A. riverbed where the concrete walls would go for miles. Creating art and painting graffiti was the most exciting art form I could do as a young man. Graffiti was always a personal journey, I was not looking for fame or chasing the dollar, it was my own challenge to follow the path and let graffiti art/life take me.

Norton, you have been collaborating with musical ensembles for live art painting performances since 1979. How would you describe the connection between music and art?

(Norton): The membranes between different disciplines like painting and music is very porous if the artist has something to say, like the beauty and freedom of the human race. But if the artist has nothing to say, the wall separating these different disciplines is solid and harmony is never obtained. Since the late 70’s, I have never meet a musician of any stature who has not considered my painting an intricate part of the performance, and that the performance would be incomplete with out it. When Panic started performing in the punk clubs in the early 80’s it was never considered an oddity. A band with a painter was just noted as right. The punk scene went around the normal avenues of public exposure. The gatekeepers like museum curators and music promoters became irrelevant. They are no more than puppets for the market and political forces. Nowadays they are back in control and have their hand on the faucet again.

Gary, even though you grew up in South Central LA and not in Mississippi, can you explain how you became involved in the blues music scene and how was it back then?

(Gary): The Eastside neighbourhood was alive and rich with its mix of cultural and musical influences. Upon entering high school, my upwardly mobile parents had moved us to “The Westside”, which stretched to La Cienega Boulevard on the western border. Mostly middle class working families inhabited this diametric opposite from “The Eastside”, but there was a big difference, a shocking difference. The racial divide had shifted; I had never been in the company of so many White and Jewish people, I had to learn the difference, it took a year. In the late 50’s to the early 60’s, and catering to a new middle class, The Westside saw a burgeoning of clubs and bars that presented live music, mostly jazz, the smaller clubs had organ combos. Many a high school night was spent in these venues witnessing some of the giants of jazz playing the hippest music in the world. John Coltrane, Art Blakley and The Jazz Messengers, Charlie Mingus played The It Club, Cannonball Adderley at The Metro, Miles Davis Quintet at The Adams West with Ike and Tina Turner Review, James Brown, Little Milton, B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, Big Mama Thornton, Lowell Fulson to name a few that were there back in the day. A big part of that education was understanding that Jazz, an original American art form, came from the Blues with its roots deep in American history. In ’64 I found myself in jail after being involved in a civil disobedience. At that time I carried a Bb Hohner Marine Band in my back pocket. For some reason I kept that harp even through arrestand booking. After being shuffled around from joint to joint, I landed in a dormatory next to a Black Man who also had a Bb Marine Band, What are the odds? Having carried that harp in my back pocket for months, and blown away by the fact that here was a complete stranger with the same harp, I had to ask, “Where is the Blues?”, He looked at me and simply said, “Between the 2nd and the 3rd holes”. WHAT!? 2nd. and 3rd. hole? The next day I was shipped out to another facility and never saw that Cat again, but I did get my 1st. blues harp lesson. I played and played until I found it, The Blue Note. This was the kick start to my adventure into the Blues World, one that I’m still involved in and have commanded a modicum of respect amongst my peers.

Dave, you were raised in Northeast L.A. during the 70’s and got involved in the punk scene. What do you remember about those days when music had a stronger meaning?

(Dave): The LA Punk Scene of the late ’70s and early ’80s was extremely eclectic. It was not just “Punk Rock”, though it all seemed to be under that heading. That scene was so alive and to this day, propels and inspires so much. It included the “multi cultural” idea, with bands like X, Los Plugz, Top Jimmy and the Rhythm Pigs, Black Flag, etc., all meeting on common ground. I worked for Bill Mentzer, who started Hully Gully Studios, and I helped build the studios around 1980, near NELA and the LA River. This studio had all the bands rehearsing there of consequence in the scene. Like the scene itself, it burned hot, then flamed out after several years, but it could never be forgotten. The Dissidents formed around ’83, and we pushed the eclectic envelope as far as we could, fusing Punk, Funk, Metal, Avant-Garde Jazz, Reggae, etc. We also flamed out, but left an imprint on later bands.

John, how would you describe the civil rights movement influence in the 60’s and 70’s from a surfer’s point of view?

(John): I grew up in a predominately living in a white community with my German, Dutch, Jewish, English family, but I was a white boys in the 50’s as the surfer from Palos Verdes. El Segundo High School had one black boy and one Asian girl. Race had nothing to do with color, in fact I was so white that my buddies would call me the reflector in the summer light of the day. I remember being at Boomer’s surf spot in La Jolla and there was one Black Bodysurfers talking with us, it was different. At 19 I moved to art school in the city and in the classroom were international students. Last when I enrolled a Chouinard Art Institute I was nearer to the downtown area that was very multinational. During the later 60’s and 70’s, I ate in Little Tokyo mostly ever night. But on the other hand I rented my Kingsley Studio that came with a Japanese gardener. In the 90’s I met Chris Blackwell from Jamaica of Island Record who bought into the Fatburger Restaurant Chain. He had set up a black Entrepreneur relation with fund, I would design the Fatburger look and work closely with two black executive for five years of which I learned a lot from as to how the world work if you were black. So all was not just about hamburgers, it was about selling hamburgers to everyone made by blacks. The chain today has store in Dubai, Beijing, South Africa, to name 137 of them. Working in Hollywood you learned that everyone watches films, so communication today is the worldwide and we have Google in our pocket.

Chaz, can you explain us how was the awesome California Locos first exhibit in LA and what kind of works you showed there? Are there any plans to travel outside the US?

(Chaz): The California Locos group has been in the making for the last 50 years and some of us have exhibited together for 35 years. We each represent an expression of the living California lifestyle and bring a rich art history. At our first L.A. show we brought that long history to exhibit. We let the viewer experience each one of us, but they become aware of the cross breeding and deep expression of our devotion. Through skate, punk, surf, music, performance and graffiti we exhibit a contemporary and mature experience, our success story comes from our past accomplishments and milestones. As elder ambassadors of our art we have taken leadership for the California Locos movement with a message and voice and feel that it has a universal appreciation throughout the world. But could only have been invented in Southern California, a unique privilege.

Norton, as an artist involved in the music scene, when do you think “alternative culture” became mainstream? Maybe it was in the mid 80’s with the sudden success of MTV?

(Norton): One of the great avenues for getting the punk alternative energy out to the public was the New Wave Theater. New Wave Theater was a crazy “free for all” cable show in los Angeles with Peter Ivors as host. The best camera, lighting, and sound people in the industry devoted their skills free to producing the program about the underground creative scene in the mid 80’s. The big money power brokers who wanted to regain control of the message crushed this and MTV was the hammer. They put millions into video of the big bands who had nothing to do or say about real world. MTV redirected the message into a more politically controlled managed message. Leaving musicians and artist to again move underground into the alternative world, which is still strong and alive and free from the market place. Here you have people who have something to say, no mater what the median is or how its combined will be heard…

Gary, how do you remember you experience at the Chouinard Art Scool in Los Angeles?

(Gary): All the best art students from all over the U.S. and the world were there, most in the applied arts: animation, design, fashion, ceramics, photography and illustration. Fine art: painting, drawing, printmaking and sculpture, was where in my 3rd. year I decided to focus my concentration. There, students could move freely between disciplines and open dialogues were encouraged. Creativity was a highly prized commodity, making something out of nothing a necessity. All the instructors in the advanced studios were active in their discipline lending a contemporary dialogue to the study. The value on my time at this school is immeasurable, as it has had a lasting effect. I do not practice politics. I deal with things that move me and things that compel me to tell a visual story by combining seemingly disparate images of these things and making them interesting visually. The payoff for my endeavour is how others interpret and express what they experience, politically or otherwise. By and large I paint for myself, Art for Art’s sake but I’ve learned that as an Artist an audience is a necessary adjunct.