Contact High.

La representación del primer hip hop

6 July 2022 Texto: AES Rando. Fotografía: Archivo Contact High. Fotografía de cada autor.

{english below} Contact High es un ejercicio de recuperación de la memoria visual del hip-hop. El libro editado por Vikki Tobak reúne a algunos de los fotógrafos del hip-hop mas importantes, con fotografias de muchos artistas antes de que éstes se convirtieran en un fenómeno global. Es en esta cercanía a lo diario donde está el valor de este libro en el que vemos a futuras estrellas mundiales y a otros que se quedaron en el camino. Una historia polifónica que nos devuelve a los vibrantes orígenes de algunos artistas legendarios del hip-hop.

¿Cómo fue tu contacto con la cultura del hip-hop?

Trabajé en el libro durante, aproximadamente, tres años, entrevistando a cada fotógrafo uno por uno y visitando sus archivos para revisar las imágenes, pero la decisión de escribir el libro se remonta aún más atrás. Creciendo como una niña inmigrante en una ciudad tradicionalmente afroamericana como Detroit, la música se convirtió en parte de mi historia. Mi familia emigró de Kazajstán a Detroit cuando yo tenía 5 años y empecé la escuela sin hablar inglés. Fue la música de las primeras radios de Detroit, Stevie Wonder y Aretha Franklin y la primera música house, lo que me dio la idea de lo que llegué a entender como América; definió mi comprensión de la cultura y el papel que la música jugó en la creación de la historia. Me enamoré del hip-hop cuando era adolescente y me sentía atraída por Nueva York. A principios de los 90, con 19 años, me mudé a Nueva York desde Detroit y conseguí un trabajo en Payday Records/Empire Management. En ese momento, Payday representaba a algunos de los nombres más importantes del hip-hop underground: Jeru the Damaja, Masta Ace, el primer grupo de Mos Def, el primer contrato de singles de Jay-Z… Pero Gang Starr es por lo que el sello era realmente conocido. Trabajé con ellos mientras grababan “Hard To Earn” como directora de publicidad y marketing. Eso significaba responder a las solicitudes de entrevistas y organizar las sesiones de fotos (básicamente asegurándome de que sonaran y se vieran bien en los medios). Los acompañaba en todas sus sesiones, sus entrevistas, y me sumergía en ese mundo. Viajé con ellos, viajé por todo el mundo con ellos, y aprendí lo que era crear imágenes sobre la marcha que tendrían repercusión mundial. Después del sello, me convertí en una periodista de música y cultura. Más tarde, cuando empecé a trabajar como productora para la CNN y la CBS y profundicé en el fotoperiodismo, los puntos empezaron a conectarse. Me interesó mucho la forma en que las organizaciones tratan sus archivos y pensé en las imágenes del hip-hop; cómo todos estos años después tenemos este vasto archivo, pero no las historias de la cultura en ese momento. Este libro fue mi manera de contar una historia más matizada de la cultura a través de la lente del fotógrafo.

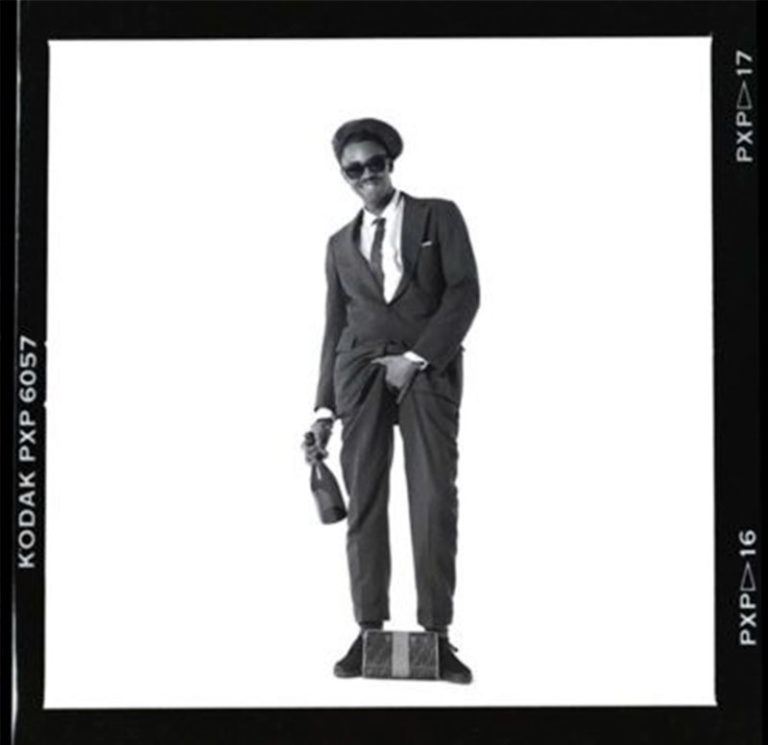

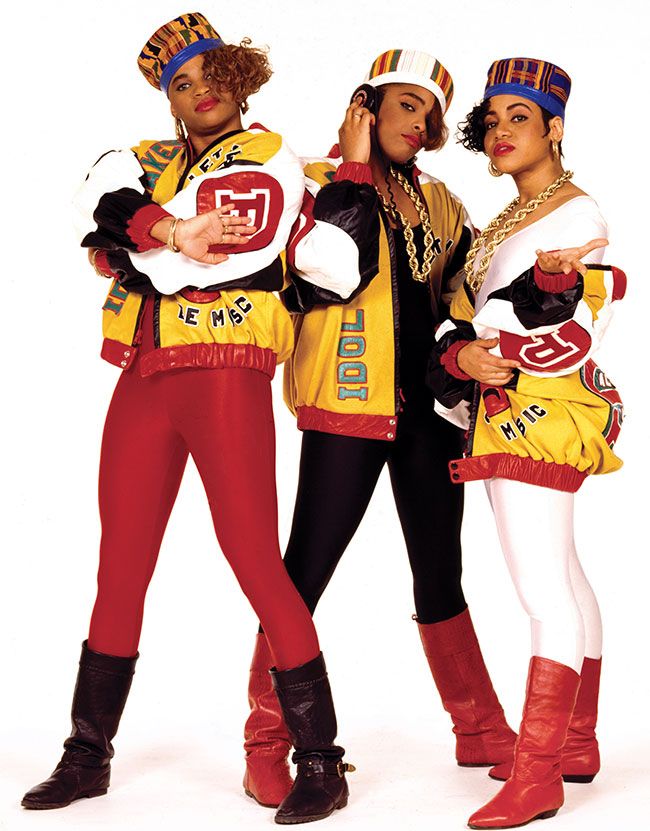

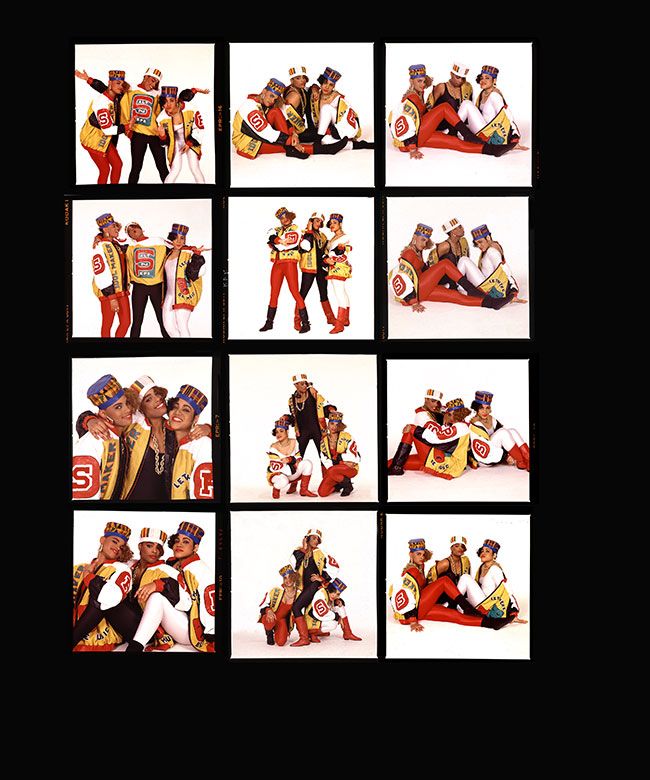

Salt n Pepa por Janette Beckman

¿En qué momento se empezó a gestar el proyecto?

Cuando me propuse hacer este proyecto, quería celebrar el legado visual del hip-hop. El hip-hop es ahora una fuerza global y quería rastrear su identidad visual hasta las raíces. La gente siempre supo cómo sonaba el hip-hop pero, ¿cómo era? ¿Y quién estaba documentando el ascenso de esta cultura? Mirar hacia atrás a ciertos fotógrafos e iconografía y ver este vasto archivo de imágenes cuenta una historia importante y poderosa. Antes de que el hip-hop se hiciera popular en todo el mundo, los fotógrafos de este libro ya hacían fotos y documentaban esta emergente forma de arte. Sentí una gran responsabilidad de hacer lo correcto con la música que cambió mi vida.

¿Cambió la concepción del proyecto durante su elaboración?

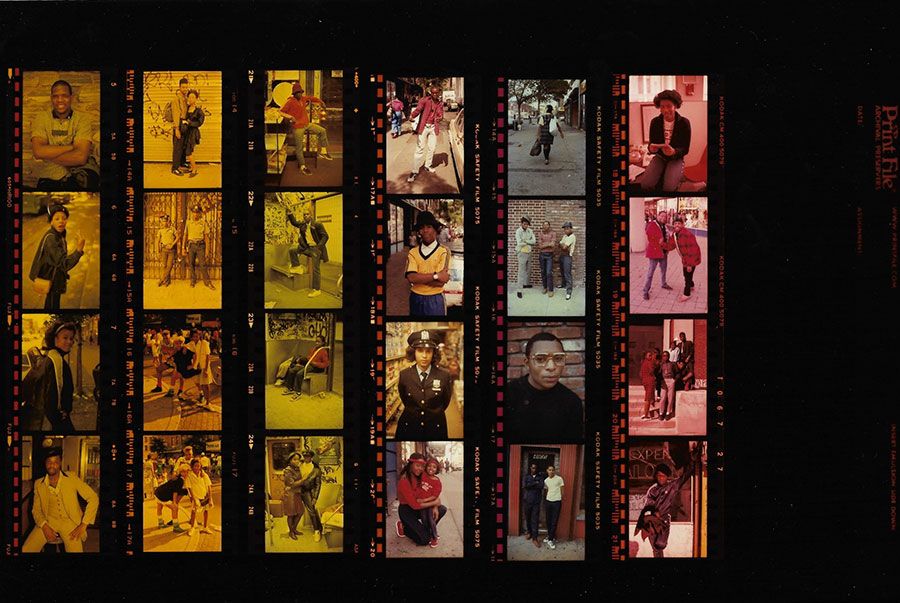

Como responsable, visité docenas de archivos y me sorprendió la cantidad de imágenes que todavía están ahí fuera. Algunos de estos fotógrafos no habían mirado sus hojas de contacto en años y se sorprendieron de lo que vieron mirando las tomas después de tantos años. Estos carretes, muchos almacenados en cajas de zapatos y armarios, guardaban momentos icónicos escondidos aún sin procesar. Las tomas intermedias en las hojas de contacto cuentan una historia más profunda; muestran la íntima relación entre el fotógrafo y el sujeto y cuánto ha evolucionado el hip-hop.

Fotos: Jorge Peniche. Hoja de contactos de Kendrick Lamar

¿Qué imágenes te interesaban para contar esta historia?

Empezó con las imágenes conocidas como Biggie “King of New Yok” pero rápidamente me interesé en las fotos más cándidas que tenían una historia sobre el lugar y el espacio y las verdaderas cosas que informaban sobre la cultura hip-hop, no sólo una llamativa portada de álbum. Hay una foto de Nipsey Hussle en la exposición tomada por el fotógrafo Jorge Peniche que también era amigo de éste, manager de la gira y socio de negocios; es una foto de Nipsey sentado en su coche frente a la oficina del correccional de Los Ángeles el día que lo dejaron en libertad condicional. La hoja de contacto lo muestra más tarde ese día con su hija sentada en su regazo fingiendo que conduce el coche. Llevaba gafas de sol en forma de corazón, y estaba pasándolo muy bien con su padre. Nipsey había compartido con Jorge que eso es algo que les gusta hacer juntos y él capturó ese momento de la paternidad y, Hussle, estaba simplemente siendo humano; esas son las fotos que me interesaron cada vez más, porque contaban una historia más grande.

EAZY E en Venice, 1989. Foto: Ithaka Darin Pappas

Ahora que el hip-hop es conocido en todo el mundo ¿es importante crear un relato de sus inicios y recordar el trabajo de gente que quizás ya no es conocida?

Quería entender cómo se creaban estos momentos clave, quién tomaba las decisiones y cómo querían ser retratados los artistas. Hoy en día hablamos mucho sobre la auto-autoría con imágenes y quién controla la narrativa. Los artistas de hip-hop estaban creando música que cambió el mundo y querían que sus fotografías formaran parte de ese mensaje. Rza escribe en su ensayo para el libro sobre el legado visual de Wu-Tang: “llegaron a la industria de la música queriendo esquivar todas las tendencias”. Les atrajeron las imágenes de las películas de kung-fu por la camaradería y la hermandad de esas primeras películas; todo esto se ve en su colaboración con Danny Hastings para la portada del álbum debut de Wu-Tang. Cuando el artista y el fotógrafo se ponen así, es mágico, dejan un auténtico legado. Muchos de los fotógrafos llegaron junto a los artistas, ambos construían sus carreras al mismo tiempo, lo que es muy distinto en otros géneros. Muchos de estos fotógrafos no estaban formados profesionalmente, sólo tuvieron el instinto de documentar el hip-hop antes de que el mundo les diera luz verde: el colectivo de fotógrafos que documentó esta hermosa cosa que llamamos hip-hop.

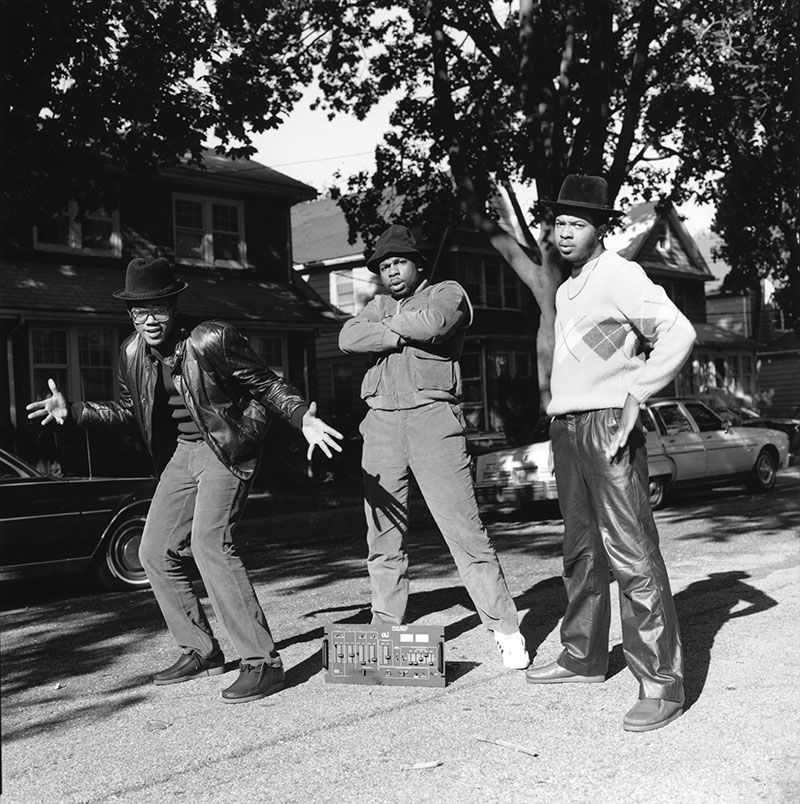

Foto: Janette Beckman. RUN DMC

Con el interés que tienen las grandes instituciones culturales por controlar, en cierta manera, la narración y la forma de presentarlo al público, ¿qué se puede hacer contra esa máquina de producir imaginarios?

Sólo hay que asegurarse de que las personas que tienen sus corazones, mentes y conocimiento de lo real en el lugar correcto sean las que están al mando. Es realmente difícil porque las instituciones, a menudo, sólo quieren celebrar el factor “cool” del hip-hop sin considerar la cultura, la historia y las circunstancias en que nació y eso es peligroso para su historia; así que los escritores y comisarios necesitan retroceder para avanzar hacia algo mejor.

¿Cuál crees que es el pago que ha tenido que hacer el hip hop para hacerse “respetable”?

No sé si “respetable” es la palabra correcta, ¿quizás “mainstream”? Ahora los niños de los suburbios aman el hip-hop obviando aspectos fundamentales de su historia. Personalmente, eso me entristece, pero también es así.

Estoy feliz de que el hip-hop haya alcanzado ese poder, mira a Jay, Diddy y Nas, teniendo poder en campos más allá de lo musical; eso es crecimiento. Pero hay contradicción en todo esto… Por ejemplo, la relación entre el hip-hop y la industria de la moda: cuando marcas como Polo, Hilfiger… No querían que los artistas de hip-hop usaran sus cosas. Pero la verdadera moda hip-hop le dio la vuelta al asunto… ese rechazo dio pie a grandes empresarios de la moda como Karl Kani, Dapper Dan, FUBU, April Walker, incluso tengo que mencionar a los Lo-Life’s aquí ¡Eso es muy poderoso! Y ahora, estas marcas, están rogando a los artistas que se sienten en el front row de sus desfiles y usen su ropa… Es tan irónico. Realmente quería contar esta historia en el libro también, así que en él encontraréis las fotos de Rakim con su chaqueta hecha por Dapper Dan con el símbolo de la bandera Universal Flag #7; Run-DMC posando en su vecindario de Hollis Queens dando poder a Adidas y Kangol; En muchas de estas fotos se ve la evolución del estilo y la moda de la calle, ya que compañías como Phat Farm, Triple Five Soul, Wu-Wear y FUBU (cuyo nombre: For Us, By Us, habla del espíritu del hip-hop que sobrevive hasta hoy) diseñaron ropa que definió aún más la identidad visual del hip-hop. La moda hizo que los diseñadores y estilistas: Dapper Dan, Groovey Lew, Sybil Pennix, Mysa Hilton, June Ambrose… Fueran arquitectos de un legado visual muy específic.

Foto: Janette Beckman. RUN DMC. 1984

El hip hop es la historia de los emigrantes, trabajadores pobres, desposeídos… ¿Qué crees que nos ilumina de la historia reciente de USA?

De hecho, también añadiría que es una historia de mujeres. Estoy orgullosa de cuantas mujeres forman parte de este libro y han hecho importantes contribuciones a la cultura.

¿Hoy día sería posible hacer ese tipo de fotos?

Hoy en día, la forma en que digerimos y creamos imágenes culturales ha cambiado radicalmente. Antes los editores y publicistas solían editar lo que el público veía… Ahora el paisaje visual tiene una forma más “aleatoria”. El hip-hop siempre ha consistido en hacer algo partiendo de poco o nada: dos tocadiscos, un micrófono, un trozo de cartón y una lata de pintura en spray. Pocos sabían que estos simples artículos producirían la mayor innovación cultural americana. Eran rebeldes, artistas que entendían el poder de las palabras e imágenes. También lo hicieron los fotógrafos que capturaron estas instantáneas. Desde retratos creados en el estudio hasta tomas de estilo documental, estas fotos hablan de una intimidad y confianza entre el artista y el fotógrafo. Algunos fotógrafos pudieron obtener su foto instantáneamente mientras que otros se tomaron su tiempo con un rollo completo de 36 disparos para hacerlo bien. A menudo comparado con el cuaderno de bocetos de un artista, una hoja de contacto es un vistazo íntimo al proceso de trabajo. Da la sensación de estar entre bastidores, de caminar junto a los fotógrafos y ver a través de sus ojos. La fotografía individual puede ser nuestra imagen definitoria, pero la hoja de contacto muestra los disparos de éxito o fracaso, las sobre o subexposiciones, la incertidumbre, e incluso la naturalidad de ese momento, así como la disciplina y el rigor de la fotografía analógica. Los fotógrafos normalmente no muestran sus hojas de contacto, es su diario visual y mostrar las fotos que fueron errores o no funcionaron no siempre es fácil para ellos. Ser capaz de mirar más profundamente en las imágenes más reconocidas del hip-hop es algo único. Estas fotos fueron hechas en momentos de confianza y admiración mutua; algunos de los fotógrafos de este libro incluso empezaron como tour mánagers y confidentes; Estevan Oriol con Cypress Hill y Jorge Peniche con Nipsey Hussle. Otros, como Gordon Parks, ya eran leyendas cuando fotografiaron hip-hop. Pero la mayoría de los involucrados dirán, antes que nada, que éramos fanáticos de la música y la cultura; incluso si el resto del mundo aún no había entendido el legado imperecedero y la excelencia de la cultura que se estaba creando.

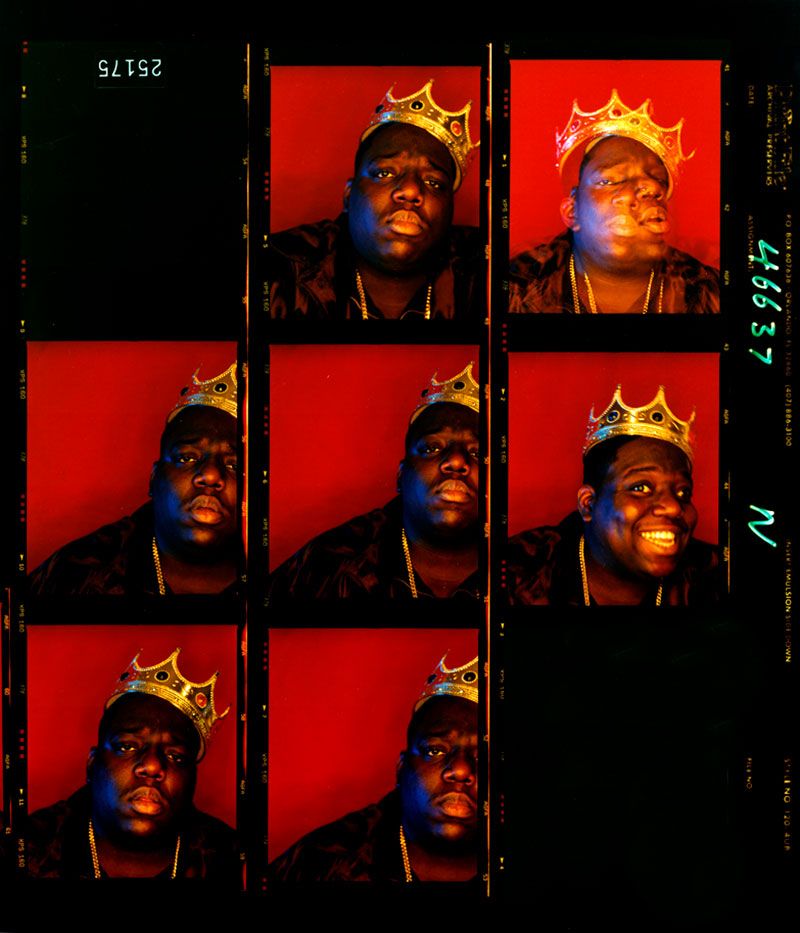

Foto: Barron Claiborne. Biggie

¿Cómo crees que ha cambiado la forma de representar a los artistas en estas últimas décadas?

Me di cuenta de lo importante que eran las historias orales del fotógrafo en la narración general. Los fotógrafos tienen algunas de las mejores historias y estaban allí, los momentos más íntimos entre bastidores. Ellos ven a los artistas frustrados, trabajando, cometiendo errores… Todos esos momentos clave. El público sólo suele ver el producto terminado, la toma perfecta, la canción perfecta… Yo quería las partes desordenadas, las dificultades y la superación; es una historia universal tanto para los artistas como para los fotógrafos. Los fotógrafos entienden que sus fotos son parte de una conversación más amplia sobre la identidad, la cultura, la raza y todo lo que el hip hop ha manifestado como parte de un documento cultural más amplio, así que me pregunté: ¿Qué decisiones se estaban tomando a lo largo del camino sobre las imágenes que darían forma al hip-hop? Al acceder a estas hojas de contacto originales e inéditas, podemos ver cómo los fotógrafos pensaron en la secuenciación, cuándo hacer clic en el obturador y cómo tomaron fotos desde diferentes perspectivas… Dejan que el espectador observe todas las tomas realizadas durante esos momentos legendarios o lo que el icónico fotógrafo callejero Henri Cartier-Bresson acuñó “El momento decisivo”. Las hojas de contacto son como si se les dejara entrar en un secreto, ir entre bastidores, profundizar en la historia

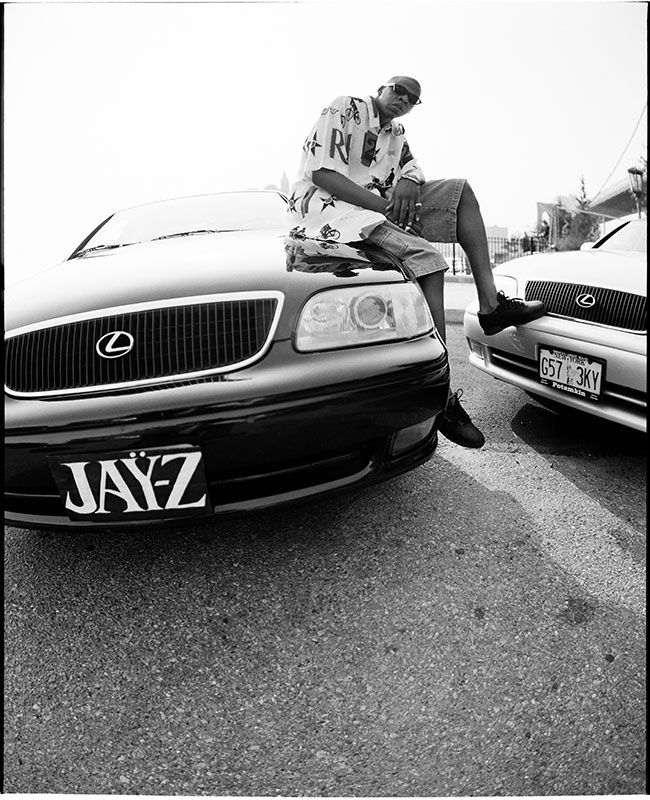

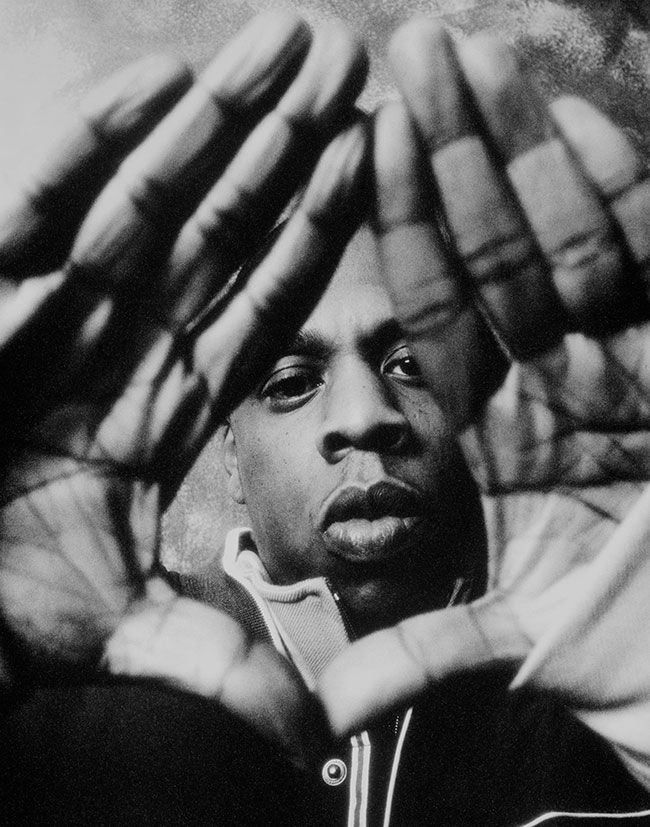

Jay Z. Foto: Jamil GS

En el libro encontramos muchas fotos icónicas, pero pienso que la de Notorius Big con la corona se ha convertido en una imagen que representa la popularización de la cultura del rap ¿qué es lo que convierte a una imagen en un símbolo?

La imagen de Biggie es un símbolo de realeza y dignidad. El fotógrafo Barron Claiborne, que también era un joven cuando se tomó esta foto, quiso retratar a Big como un rey de África occidental en contraposición a la forma en que se veía a los jóvenes negros retratados en los medios de la época (finales de los 90).

El libro también se ha convertido en una exposición ¿Comisarías tú las exposiciones?

Sí, comisarié la exposición que ahora está en el Centro Internacional de Fotografía (ICP) de Nueva York y que viajará a otras ciudades del mundo.

Jay Z. Foto: Jamil GS

Jay Z. Foto: Jamil GS

Salt & Pepa. Foto: Janette Beckman

Jay Z. Foto: Armen Djerrahian

Tyler The Creator. Foto: Jorge Peniche

Fab Five Dreddy. Foto: Sophie Bramly

Queen Latifah. Foto: Al Pereira

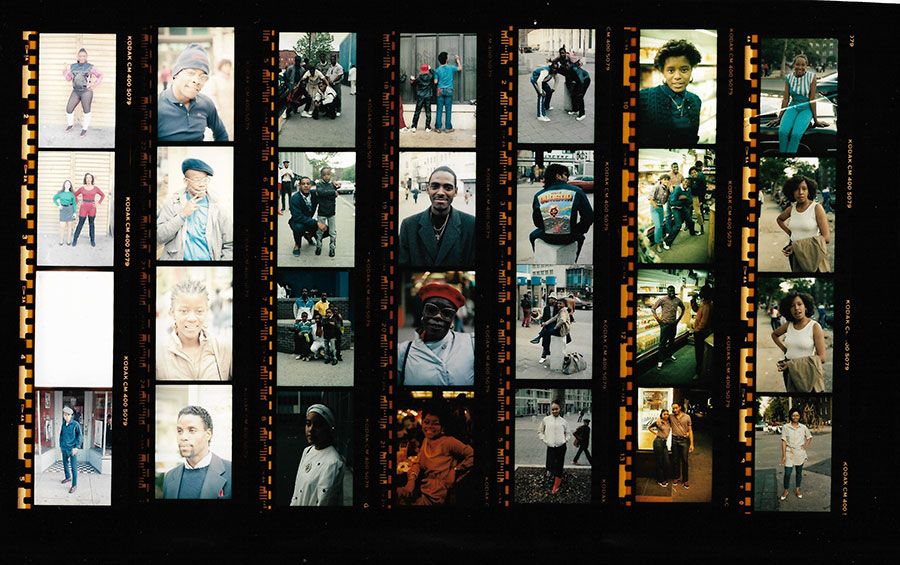

Fotos de: Jamel Shabazz

Fotos de: Jamel Shabazz

Foto de: Janette Beckman

Lauryn Hill. Foto: Jayson Keeling

Foto: Joe Conzo

Tyler The Creator. Foto: Jorge Peniche

Slick Rick. Foto: Janette Beckman

English:

CONTACT HIGH: EARLY HIP-HOP REPRESENTATION

Contact High is a visual memory recovery exercise for some legendary hip-hop artists. The book edited by Vikki Tobak brings together some of the best photographers of hip-hop culture, before it became a global phenomenon. And it is in this close proximity to the newspaper that the value of this book lies, in which we see future world stars, others who fell by the wayside or were left half way through. A polyphonic story that takes us back to the vibrant origins of some of these great hip hop artists.

How was your contact with the hip-hop culture?

I worked on the book for approximately three years interviewing each photographer one by one and visiting their archives to go through imagery. But my coming to write the book goes back even further. Growing up an immigrant kid in a traditionally African-American city like Detroit, music became a part of my story. My family emigrated from Kazakhstan to Detroit when I was 5 years old and I started school not speaking English. It was the music on early Detroit radio, Stevie Wonder and Aretha Franklin and early house music, that gave me a window into what I came to understand as America. It defined my understanding of culture and the role music played in creating narratives and history. I fell in love with hip-hop as a teenager and was drawn to New York,. In the early 90’s at 19 years old, I moved to New York from Detroit and got a job at Payday Records/Empire Management. At that time, Payday represented some of the most important names in underground hip-hop: Jeru the Damaja, Masta Ace, Mos Def’s first group, Jay-Z’s first singles deal — but Gang Starr is what the label was really known for. I worked with them as they were recording Hard To Earn as the director of publicity and marketing. That meant fielding interview requests and arranging photo shots, basically making sure they sounded and looked right in the media. I would accompany them on all their shoots, their interviews, and I got immersed in that world. I toured with them, I traveled the world with them, and learned what it was like to see the images being created along the way be put out into the world. After the label, I became a music and culture journalist. Later on, when I started working as a producer for CNN and CBS and went deeper into photojournalism, the dots started to connect. I became really interested in the way organizations treat their archives, and thought about hip-hop imagery — how all these years later we have this vast archive, but, we don’t have the stories behind what was happening within the culture at that time. This book was my way of telling a more nuanced story of the culture through the photographer’s lens.

When did the project start?

When I set out to do this project, I wanted to celebrate hip-hop’s visual legacy. Hip-hop is now a global force and I wanted to trace the visual identity back to the roots. People always knew what hip-hop sounded like “but what did it look like”? And who was documenting the culture’s rise from the star? To look back on certain photographers and iconography and see this vast archive of imagery tells an important, powerful story. Before hip-hop became popular worldwide, the photographers in this book were taking pictures and documenting the nascent art form. I felt a huge responsibility to do right by the music that changed my life.

Did the conception of the project change during its development?

As responsibility to the images, I visited dozens of archives and was surprised at just how many images are still out there. Some of these photographers hadn’t looked at their contact sheets in years and were surprised at what they saw looking at the outtakes after so many years. These rolls of film, many stored away in shoeboxes and closets were holding iconic moments tucked away, still unprocessed. The in-between shots on the contact sheets tell a deeper story; they show the intimacy between the photographer and the subject. And they show just how much hip-hop has evolved.

What images were you interested in to tell this story?

It started out with the well known images like the Biggie ‘King of New Yok’ but quickly I became more interested in the more candid photos that had a story about place and space and the true things that informed hip-hop culture. Not just a flashy album cover. There’s a photo of Nipsey Hussle in the exhibition taken by photographer Jorge Peniche who was also Nipsey’s friend, tour manager and business associate. It’s a photo of Nipsey sitting in his car in front of the LA corrections office the day he was let off probation. The contact sheet shows him later that day with his young daughter sitting on his lap pretending to drive his car. She’s wearing heart-shaped sunglasses just having a great time with her dad. Nipsey had shared with Jorge that that’s something they like to do together and he captured that moment of fatherhood and Nipsey just being human being. Those are the photos I became more and more interested in because they told a larger story.

Now that hip-hop is known all over the world, is it important to create an account of its beginnings and to remember the work of people who may no longer be known?

I wanted to understand how these touchstone moment were being created, who was making the decisions and how the artists wanted to be portrayed. These days we talk a lot about self-authorship with imagery and who controls the narrative. Hip-hop artists were creating a music that changed the world and they wanted their photographs to be part of that message. Rza writes in his essay for the book about Wu-Tang’s visual legacy: they came into the music industry wanting to buck all trends. He was drawn to the visuals of kung-fu movies for the camaraderie and brotherhood of the early kung-fu flicks. You see all of this play out with his collaboration with Danny Hastings for the cover of Wu-Tang’s debut album. When the artist and photographer get eachother like that, it’s magic. It’s legacy building. Many of the photographers came up alongside the artists. Both were building their careers at the same time, which is different from other genres. Many of these photographers weren’t professionally trained. They just had the gut instinct to document hip-hop before the world gave them permission. the collective of shooters who documented this beautiful thing we call hip-hop.

With the interest that large cultural institutions have in controlling the narrative and the way it is presented to the public, what can be done against this machine of producing imaginaries?

Just making sure the people who have their hearts and minds and understanding of the real culture in the right place are in the driver’s seat. It’s really difficult because institutions often just want to celebrate the “cool” factor of hip-hop without considering the culture, history and circumstances it was born out of. And that’s dangerous to history. So writers and curators really need to push back and push through to something better.

What do you think hip-hop has had to pay to become “respectable”?

I don’t know that ‘respectable’ is the right word. Maybe ‘mainstream’? Now it’s safe for suburban kids to love hip-hop without being all in on all the aspects (good, bad and ugly) of the history. Personably, that makes me sad but it’s also just the way it is.

I’m happy that hip-hop has stepped into its power – look at Jay and Diddy and Nas all having power in realms beyond just the music aspect. That’s growth. But there is an irony to it all. For example — I kept coming back to this great irony with hip-hop and the fashion industry. When brands like Polo, Hilfiger, none of them wanted hip-hop artists wearing their stuff. But in true hip-hop fashion they turned the whole thing on it’s head..that rejection gave birth to great fashion entrepreneurs like Karl Kani, Dapper Dan, FUBU, April Walker, I even have to mention the Lo-Life’s here. That is so powerful! And now these brands are begging for artists to sit in their front row and wear the clothes. It’s so ironic. I really wanted to tell that story in the book as well so you’ll notice photos Rakim rockin his Dapper Dan made jacket with the #7 Universal Flag crescent Five Percenter symbol; Run-DMC posing in their neighborhood of Hollis Queens giving power to Adidas and Kangol; In alot of these photos, you see the evolution of street style and fashion as companies such as Phat Farm, Triple Five Soul, Wu-Wear, and FUBU (whose very name—For Us, By Us—speaks to a spirit in hip-hop that lives to this day) designed clothing that further defined brought hip-hop’s visual identity. Fashion, making designers and stylists — Dapper Dan, Groovey Lew, Sybil Pennix, Mysa Hilton, June Ambrose — architects of a very specific visual legacy.

Hip-hop is the story of immigrants, the working poor, the dispossessed. What do you think illuminates the recent history of the United States?

Indeed and I would also add that it’s a story of women – I’m proud of how many women are part of this book and made important contributions to the culture.

Would it be possible to take that kind of pictures today?

Today, the way we digest and create cultural imagery has radically changed. Where once editors and publicists used to edit down what the public saw, .today’s visual landscape is haphazardly shaped from every direction. Hip-hop has always been about making something out of little or nothing: two turntables, a microphone, a piece of cardboard, and a can of spray paint. Few knew that these simple items would produce the greatest American cultural innovation. They were rebels, artists who understood the power of words and the power of imagery. And so did the photographers who captured these images. From portraits created in the studio to documentary style shots, theses photos speak to an intimacy and trust between artist and photographer. see the full range of images. Photographers, editors and artists used them to decide on the “money shot.” Some photographers were able to get their shot instantaneously while others took their time with a full roll of 36 photos to get it right. Often compared to an artist’s sketchbook, a contact sheet is an intimate glimpse into the working process. It gives a behind-the-scenes sense of walking alongside photographers and seeing through their eyes. The single photograph may be our defining image, but the contact sheet shows the hit-or-miss shots, the over or underexposures, the uncertainty, and even the naturalness of that moment, as well as the discipline and rigor of analog photography. Photographers typically don’t show their contact sheets. It’s their visual diary and showing shots that were mistakes or didn’t work isn’t always easy for photographers. To be able to look deeper into the most recognized images of the hip-hop, is special. These are images that were made in moments of trust and mutual admiration. Some of the photographers in this book even started as tour managers and confidants; Estevan Oriol with Cypress Hill and Jorge Peniche with Nipsey Hussle. Some like Gordon Parks were already legends by the time they shot hip-hop. But most of those involved will say, first and foremost, we were fans of the music and the culture. Even if the rest of the world had yet to understand the lasting legacy and excellence of the culture that was being created.

How do you think the way of representing artists has changed in these last decades?

I realized how important the photographer’s oral histories were in the overall narrative- photographers have some of the best stories and they were there at the most intimate behind-the-scenes moments. They see artists being frustrated, working it out, making mistakes..all these key moments. The public often only sees the finished product, the perfect shot, the perfect song. I wanted to hear about the messy parts, teh hardship and the overcoming. That’s a universal story for both the artists and the photographers. Photographers understand that their photos are part of a larger conversation about identity, culture, race and all that hip hop has manifested as part of the broader cultural document. So I wondered, what decisions were being made along the way about the imagery that would shape hip-hop? In getting access to these original and unedited contact sheets, we can see how photographers thought about sequencing, when to click the shutter and how they took photos from different perspectives. They let the viewer observe all of the other shots taken during these legendary moments or what legendary street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson coined “The Decisive Moment. Contact sheets are like being let in on a secret, going backstage, going deeper into the story.

In the book we find many iconic photos, but I think the one of Notorius Big with the crown has become an image that represents the popularization of rap culture. What makes an image a symbol?

The biggie image is a symbol of royalty and dignity – the photographer Barron Claiborne, a young black man himself when this photo was taken, wanted to portray Big as a west African king as a contrasts to how he was seeing young black men portrayed in the mainstream media at the time (late 90’s).

The book has also become an exhibition. Would you also curate the exhibitions?

Yes I curated the exhibition which is now at The International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York and will travel to other cities around the world.