{english below} Lo normal cuando sujetas en tus manos un volumen que ronda las mil páginas, es que se trate del Corán o de la Biblia, pero es raro que se trate de un libro que hable acerca del ollie, maniobra que, como cualquier aficionado al monopatín sabrá, marcó un hito en la historia de este deporte. Según Craig B. Snyder cada cultura alberga algún mito en torno a su creación y el ollie sería como la piedra filosofal del patín. Pues lo creáis o no, Ollie tiene casi mil páginas y, en cierto modo, se ha convertido también en un texto sagrado dentro de la cultura a la que va dirigido. Estamos ante la historia del ollie y de los skaters que lo inventaron y que, tomándolo como maniobra básica, fueron estirando las posibilidades del monopatín hasta límites insospechados. El libro va a compañado de fotos tan alucinantes que es difícil evitar, en una primera toma de contacto, no verlo de cabo a rabo para más tarde leerlo y completar la información visual con la que aporta el texto, escrito brillantemente por un Craig B. Snyder inspirado y con vocación de historiador. Ojo, y solamente estamos hablando de un primer volumen centrado en los 70, de manera que invito a los amantes del skate a que vayan comprándose una estantería un poco más grande.

¿Cuál ha sido tu principal motivación para embarcarte en un proyecto de este empaque?

Hubo muchas razones y todas ellas fueron igual de importantes. La primera y más evidente es contar esa parte de la historia del Ollie que jamás había sido contada. Por ser el truco más mítico del skate y por su influencia no solo en el mundo del patín, si no en la cultura popular. La segunda, era más personal, ya que el Ollie fue inventado en Hollywood, en mi ciudad. Así que si no contaba yo la historia ¿Quién iba a hacerlo? Además como “Hollywood Insider” tenía acceso a gente e imágenes que otros no tendrían a mano. En tercer lugar, el hacerle saber a la gente la influencia que Florida ha tenido en la historia del patín. Y es que muchos, incluido patinadores, siguen creyendo que el Ollie fue inventado en California.

La cuarta por la que consideré que el proyecto era importante fue que los 70 como conjunto estaba siendo olvidado. Esa década, más que ninguna otra, definió lo que sería el patín moderno. Y de ella solo se conoce un mínimo gracias a Dogtown y Z-Boys, ¿y qué hay del otro 98%? La revolución de 1970 supuso todo un movimiento en la que un gran grupo de gente trabajó para avanzar en algo. Y no solo ocurría en Cali o Florida, si no en diferentes lugares de una manera simultánea: Nueva Zelanda, Japón y Australia, construían sus primeros skateparks, y en Suecia, se creaba el primer skate camp.

Y la quinta, es mi amor por las “underdog stories”. Hay miles en el mundo del skate y pensé que este libro podría contar historias sobre skaters, fotógrafos, diseñadores de tablas y otros compañeros de la industria que nunca tuvieron el reconocimiento que merecían. Creo que es una parte que debía no ser excluida, al contrario que hacen los medios con historias de este tipo.

Por último, quise crear este libro porque no se trataba de un producto promocional, sino una historia de la que podrían disfrutar tanto patinadores como no patinadores y que podría yacer fácilmente en las estanterías de cualquier biblioteca o colegio. Mostrar la cultura skater de un modo que pudiese ser apreciada por la gente que no patina ha sido una de mis claves para llevar adelante este proyecto.

Melbourne Beach skater Shawn Jackson performing at an Orlando competition prior to the first skateparks, by Al Porterfield

¿Fue complejo el proceso de recopilación de documentos e imágenes?

Mucho. Para la parte escrita, cerrar los capítulos era imposible, ya que constantemente aparecía nueva información, así que cada semana me tocaba dar un paso atrás y revisar o reescribir alguna parte. A pesar de haber estado siete años escribiendo e investigando, siempre había algo que cambiar.

Las fotos eran otra cosa. Comparado con el texto, era todo algo más fácil, aunque de todos modos, era el cuento de nunca acabar. Aún sigo reuniendo imágenes que podrían o deberían haber estado en el Volumen I.

La mayor dificultad era el editarlas y el elegir cuáles estarían en el libro y cuáles no, ya que a pesar de que el libro cuente con unas 1200 imágenes, la cantidad que se ha quedado fuera es más o menos la misma. Mucha gente puede considerar que es un libro fotográfico, pero podría funcionar también como libro de texto sin ninguna ilustración.

Mientras tanto, en Río se celebran los Juegos Olímpicos. ¿Qué piensas sobre que el skate se haya convertido en una nueva modalidad?

Está habiendo un debate muy amplio en cuanto a este tema, sobre todo en el núcleo de la comunidad skater. Muchos creen que arruinará el patinaje pero, en mi opinión creo que no cambiará nada. Las olimpiadas son las olimpiadas, la competición es la competición y el skate es el skate; más allá de intereses económicos y la comercialización del mainstream. Además es algo que ya vimos con el nacimiento de los X Games a finales de los 90. ¿Qué es lo que va a cambiar ahora? Nada. Creo que no va a traer nada negativo. Pero bueno, habrá que esperar. Si hay algo que me gustaría, sería ver cómo los Juegos generan un mayor interés en el patín, sobre todo en sus orígenes y su cultura.

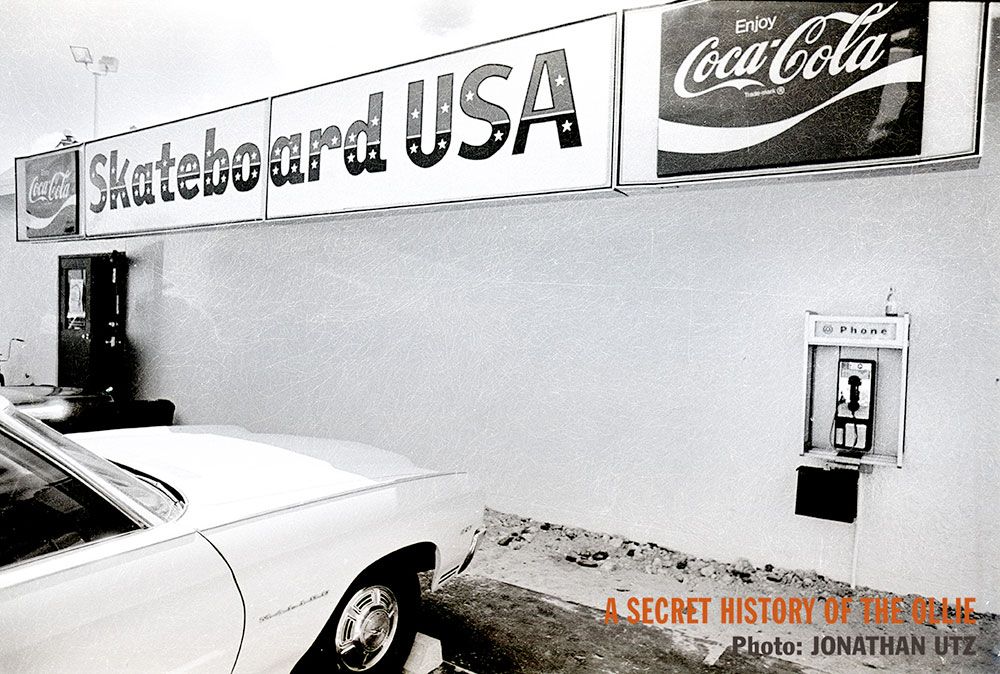

Pro shop at Skateboard USA skatepark, Hollywood, Florida, by Jonathan Utz

Eres escritor, fotógrafo y skater, ¿en qué proyectos estás trabajando en este momento?

Estoy con varias cosas ahora mismo, pero hasta ahora, en lo que he estado más ocupado ha sido en la promoción del libro. Ya sabes, firmas, viajes, charlas, muestra… También tengo varios proyectos sobre nuevos libros en mente e inlcuso, un proyecto sobre una película.

Además, al mismo tiempo que Vol.I, escribimos “Volume Two of A Secret History of the Ollie”, que se centra en los 80. El texto aún necesita revisiones y demás y para ello, necesito encerrarme de nuevo en mi habitación tal y como hice con la primera parte, pero no sé si aún estoy preparado para ello.

¿Cuáles consideras que son los rasgos más característicos del skate como cultura?

El skate es único porque tiene su propia comunidad, lenguaje y formas artísticas, incluyendo, sin duda, el acto de patinar como tal. Aunque también se concibe como deporte ya que implica una habilidad atlética, es por encima de todo, una cultura. Una cultura que, siempre ha tenido como institución el skatepark y que ha cambiado mucho a lo largo de los años. En los 60 y los 70 era mucho más singular y cerrada, pero a día de hoy, es mucho más grande y diversa. Incluso tiene subgrupos con los que antes no contaba.

Para mí, el skate tiene la misión de cambiar el mundo. No entiende de política, raza o religión y si, las nuevas generaciones son introducidas en el skate, seguro que podremos ver un cambio grande en nuestro mundo. Esta puede ser también una de las razones por las que el incluir el skate en los Juegos Olímpicos puede ser muy positivo.

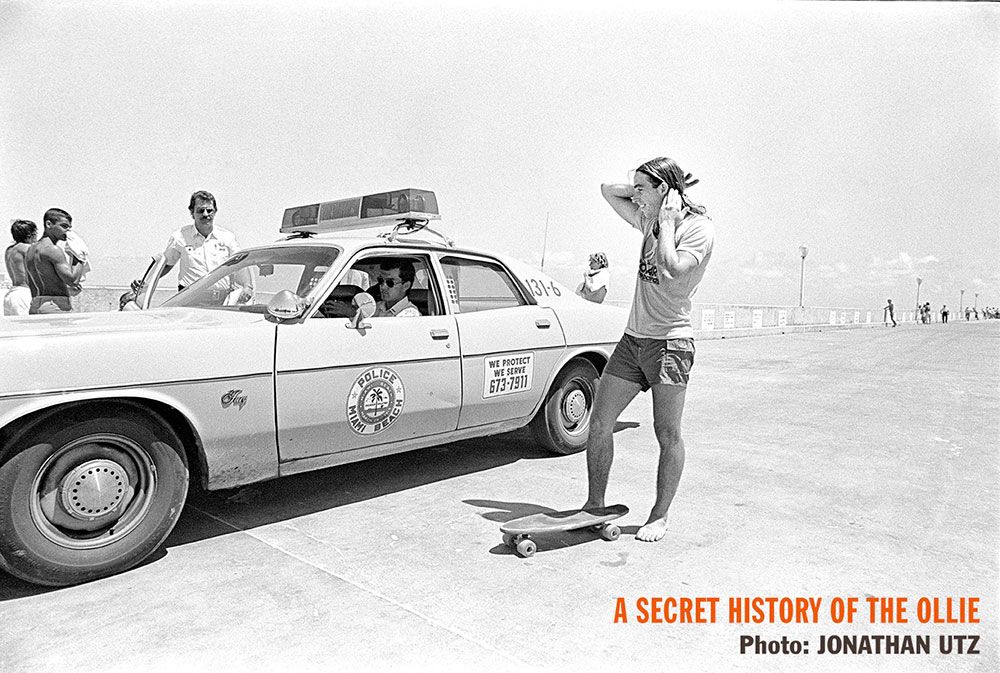

Dave Bentley being questioned by Miami Beach Police on the South Beach pier, Miami Beach, Florida, by Jonathan Utz

Cuando piensas en un truco, raramente se te pasa por la cabeza la tecnología que lo ha hecho posible. ¿Cuál crees que es la pieza clave que hizo posible la invención del Ollie?

Lo primero que se me viene a la cabeza es el kicktail, pero las ruedas de uretano y los rodamientos de precisión también fueron cruciales. ¡Y no nos olvidemos de la lija! Y el skatepark, que fue el laboratorio de creación y experimentación de muchos trucos que ahora conocemos.

Si miras hacia atrás, desde los 70 hasta ahora, puedes ver que la evolución de este deporte ha sido meteórica. ¿Crees que seguirá en el mismo camino?

Es una pregunta compleja. La década más revolucionara sin duda fueron los 70, ya que todo se probaba por primera vez. Cada año era como una década en evolución. En los 80, el patín moderno ya había nacido, tanto tecnológicamente como en cuanto a primera maniobras. El Ollie ya empezaba a pisar fuerte. Los 90, fueron una continuidad de lo que se había quedado sin terminar en los 80.

Mucha gente puede decir que ya está todo inventado, pero lo que se ve es que muchas maniobras que estaban olvidadas se están reinventando y combinando de diferentes maneras. Así que como respuesta a tu pregunta, quizás diría que el skate jamás dejará de evolucionar cada día, no solo en un plano individual, si no en el más personal.

Todd Hanak skating the Dogwood Ramp, the earliest known curved wood ramp, in Melbourne Beach, Florida, by Bruce Walker

Un libro como este solo ha podido nacer por el amor a una cultura. ¿Qué ha aportado el skate a tu vida?

El patín me dio mucho mientras crecía y quería darle algo de vuelta. Para mí es la mejor manera de dar tributo a los pioneros, sobre todo, a esos que no han sido reconocidos como tal y merecen algún lugar en la historia.

A Secret History of the Ollie era, de hecho, un proyecto sobre una pasión y, aunque yo solo lo he percibido como un libro, muchos lo consideran un trabajo artístico. Así que puede ser que sí, que sea arte, o quizá un poema, un poema al skateboarding, una oda al patín y al nacimiento de patín moderno.

Hemos evolucionado de patinar descalzos con tablas muy rudimentarias a patinar en skateparks diseñados por arquitectos. ¿Qué opinas sobre el espectáculo de la Street League?

No tengo ninguna opinión sobre eso porque no la he seguido ni sé demasiado de qué va. Pero me reitero en lo que he dicho antes, lo que es lo que hay: el skate es el skate y la competición es la competición.

Mike Folmer at Clearwater Skateboard Park in Clearwater, Florida, by Bruce Walker

Los skaters tienen su propio estilo e incluso, han cambiado la moda. En tu libro, comentas que la imagen lo era todo en la prensa de los 70. ¿qué quieres decir exactamente?

Me refiero a que en ese contexto la foto más potente era la que aparecería en la revista. Por sus movimientos o su estilo más fuera de lo común era la que más papeletas tendría para saltar a la fama. Planchar los trucos no era lo que vendía en las revistas y es más ahora incluso que antes.

Alan Gelfand fue el hombre que definitivamente inventó el Ollie, el truco que todo lo cambió. ¿Crees que otro skater podría haberlo conseguido?

Ha habido mucho debate sobre quien hizo el primer Ollie. Cuando se empezó a saber sobre el proyecto, muchos se me acercaron para hablarme sobre quién lo había hecho primero, antes de Gelfand o antes de que el Ollie se hiciese conocido. El truco no sucedió de la noche a la mañana, si no que fue un proceso de unos 8 meses entre el primer Ollie Pop en 1977 hasta el primer Ollie Air propiamente dicho en 1978. Fue, además, un proceso colaborativo entre un grupo al que me refiero en el libro como “Holliwood Contingent”. El debate siempre se centra entre tres skaters de Florida: Alan “Ollie” Gelfand, Pat Love, and Jeff Duerr, podréis verlo en el libro. Pero el punto de partida fue el Ollie Pop, y eso fue obra de Alan “Ollie” Gelfand.

Alan “Ollie” Gelfand in the lower snake run at Skateboard USA, by Jeff Duerr

¿Podrías nombrarnos a tres skaters que, en tu opinión, tengan los mejores ollies? ¿Conoces a Aldrin Garcia?

Bueno, los tres primeros que me vienen a la cabeza son Alan Gelfand, Alan Gelfand y Alan Gelfand. ¿Por qué? Porque tiene un estilo inconfundible, fluido y grácil. Después vendría David Z si hablamos de frontside Ollies. También figuras como Natas Kaupas y Mark Gonzales,de los que hablamos mucho en el Volumen II. Aldrin Garcia es el poseedor del record del Ollie de mayor altura. Tiene talento pero su proeza no juega tanto con el estilo. Estaría genial ver un concurso en el que se premiara más el estilo que la altura. Ahí cambiarían las cosas.

El surf y el skate son inseparables, ¿qué disciplina crees que es más dependiente de la otra?

Como se dicen en los estados civiles de Facebook, es complicado. El surf y el skate fueron inseparables por un periodo de tiempo, desde los 60 hasta los 70, y luego, se separaron de nuevo.

Ambas son muy independientes pero se influyen la una a la otra de muchas maneras. Al principio, era el surf el que dominaba al patín, pero ahora se ve como muchos surfistas pillan olas del mismo modo en que patinan. Ojalá fuesen inseparables, ya que el surf lleva al skate a una dimensión muy distinta. No importa lo que practiques, lo que importa es el estilo. Esa es la única cosa que proviene del surf que se mantiene inamovible.

Kelly Lynn using straps to catch no-handed air before the invention of the Ollie in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, courtesy of Kelly Lynn

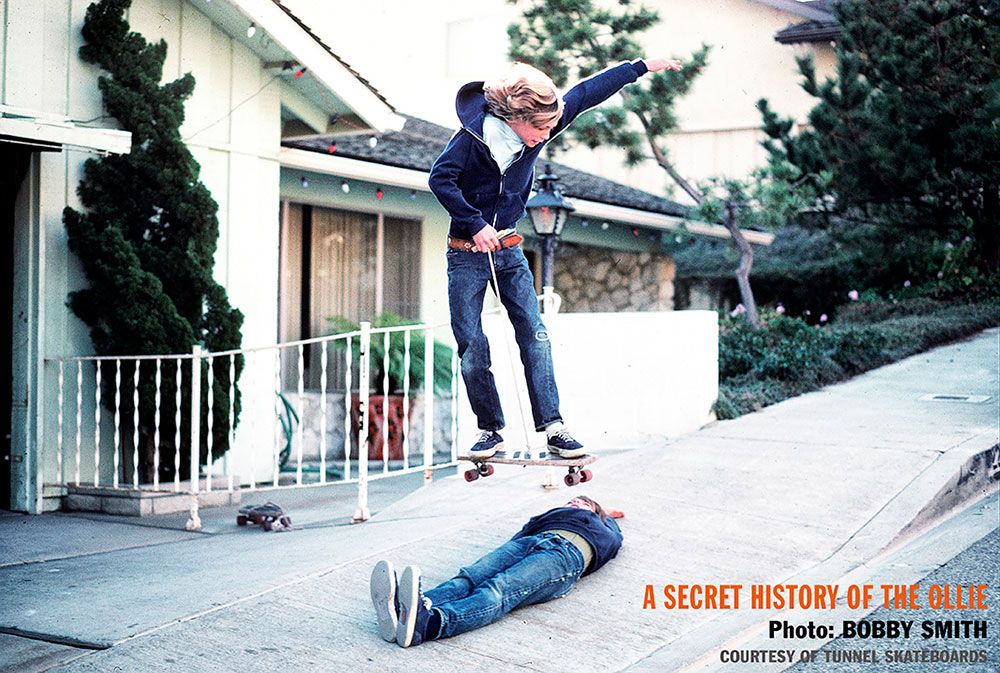

Bill Smith jumps over Dave Bentovoja using a form of early air in San Pedro, California, by Bobby Smith. Photo courtesy of Bobby Smith and Tunnel Skateboards

Clearwater Skateboard Park team at the Surferdrome skatepark in Sarasota, Florida, courtesy of George McClellan

Kim Cespedes at the Escondido reservoir in California, by Jim Goodrich

Unknown skater in the North Bowl at Skateboard USA, Hollywood, Florida, by Craig B. Snyder

Key skateparks and landmarks in California relative to the story in “A Secret History of the Ollie.” Illustration from the book by Craig B. Snyder

Key skateparks and landmarks in Florida relative to the story in “A Secret History of the Ollie.” Illustration from the book by Craig B. Snyder

Chapter 68: “Silver Platter.” Photos: (left) Scott Goodman, courtesy of Scott Goodman, (right) Gregg Weaver at Skateboard World, Torrance, California by Jim Goodrich

Chapter 67: “Standards.” Photo of Alan “Ollie” Gelfand at Solid Surf skatepark in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, by Jim Goodrich

Chapter 52: “A Turning Point.” Photo of the Turningpoint Ramp in Cocoa Beach, Florida, by Craig B. Snyder

Chapter 49: “Spring Fever.” Photo of Chuck Lagana at Rainbow Wave skatepark in Tampa, Florida, by Craig B. Snyder

Chapter 46: “Arrival.” Photo of Alan “Ollie” Gelfand at Sensation Basin skatepark in Gainesville, Florida by Craig B. Snyder

Chapter 21: “Four Wheels Out.” Photo of Kelly Lynn at Skateboard City in Port Orange, Florida, by Al Porterfield

Ad for Donel Distributors, November 1977. Photographer unknown

Chapter 17: “Beware of Imitations.” Photo of David Paul, Lee Jespersen, Murray Estes, and Henry Ward at the Kona Bowl swimming pool, Escondido, California, by Lance Smith

English:

A SECRET STORY OF THE OLLIE VOL 1: THE 1970s.

THE SACRED TEXT OF THE SKATE

When you hold in your hands a volume of around one thousand pages, the first think may come to mind it is the Koran or the Bible, but the rarest is that book just talks about the Ollie, the milestone of the maneuvres as any skate lover knows. According to Craig B. Snyder each culture holds some myth about its creation and the Ollie would be like the skate Philosopher´s. Believe it or not, the Ollie has nearly a thousand pages and, in some ways, it has also become a sacred text within the culture to which it is intended.

Here we have history of the Ollie and the skateboarders who invented it and stretched the skateboard possibilities to the limit from this basic. The book is accompanied by such amazing pictures that it is difficult to avoid, in a first contact, not see it from the beginning to end for later reading it and complete the visual information that provides the text, brilliantly written by Craig B. Snyder. Wait! We are only talking about a first volume focused in the 70´s so we recommend you, skate lover, to start by buying a slightly larger shelf.

What was the main motivation that led you start such a huge project?

There wasn’t a single reason, but many, and I would have to say all of them were equally important. The first and most obvious is that the story of the Ollie had never been told before. The Ollie is skateboarding’s most magical move, and considering the Ollie’s place in skating today, as well as its influence on not just skateboarding but popular culture, it was a story long overdue. Second, it was personal because the Ollie was invented in my hometown of Hollywood, Florida, and ultimately, if I didn’t tell the story, no one else would. As one of the “Hollywood Insiders,” I also had exclusive access to people, images, and other things that no one else had.

Third, it was important that people understood the influence that Florida had on skateboarding. Many people, skaters included, are under the impression that the Ollie was invented in California. Interestingly enough, when two film producers recently flew out from Los Angeles to meet with me about making my book into a film, we discussed that very misconception. On the second day, they showed up at my office telling me they had been stopping skaters on the street and pulling their rental car over to the side of the road just to ask people if they knew where the Ollie was invented. Of course, you can guess these answers. What I like to ask people is, “Where would skateboarding be today without Alan ‘Ollie’ Gelfand, Mike ‘McTwist’ McGill, and Rodney Mullen?” All three of these guys came out of Florida, and all three changed skateboarding in significant ways. As Florida’s Skateboard Hall of Fame founder Steve Marinak once put it, “All of modern skating has these three factors in them: Ollies; anything from Rodney; and McTwisting-type tricks.” In addition, the modern vert ramp also has its roots in Florida. The Hollywood Ramp, built in Hollywood, Florida in 1978, was essentially the first halfpipe with flatbottom, and it was a game-changer. It was the archetype for today’s vert ramp. During the 1980s, “Hollywoodramp” became a generic term that was used in Holland, Germany, Sweden, and other countries to mean a flatbottom style of halfpipe.

The fourth reason I thought the project was important was that the 1970s as a whole were being forgotten. That decade, more than any other, really defined skateboarding. Every piece of technology and every move that skating needed was created during this period, setting the foundation for skating as we know it today. It was the decade that gave birth to modern skating. The little history that many people do know about the 1970s, they know about three people and one place in time. It’s great that Tony Alva, Jay Adams, and Stacy Peralta got the credit they were due through Stacy’s movie (Dogtown and Z-Boys, 2001), but what about the other 98%? The revolution that occurred in the 1970s was a movement. A movement can be described as a group of people working together to advance something. Skateboarding has been and will always be about the contributions of the many. In some cases, invention was happening simultaneously in different places. And it wasn’t all happening in California or Florida; it was global. New Zealand, Japan, and Australia built the first skateparks. Sweden created the first skate camp. During the 1980s after the skateparks died, the Eurocana camp became the site of new moves like the McTwist, Stalefish, and 720. Eurocana also laid the ground for today’s skate camps like Camp Woodward.

The fifth reason for the book was I love the underdog and I love underdog stories. There are plenty of those in skateboarding, and I thought this book would provide the opportunity to tell some of those long-overdue stories. You can find them throughout the book, on different levels, and in every place the book travels. There are skaters who never got the recognition they were due. There were also photographers, board designers, equipment makers, and industry folks. I believe history should be inclusive, not exclusive, contrary to the way the media and others like to present things.

Finally, I wanted to create a book that wasn’t a product endorsement, but a genuine history that non-skaters would love as much as skaters, and that could easily sit on the shelves of every public and school library. Showing skate culture so it could be appreciated by non-skaters was one of the key objectives for this project.

Was the documentation and image compilation processes difficult?

It was extremely difficult. For the text, the largest struggle was completing any one section of the book. New information or stories were constantly appearing or being dug up, and every week I had to go back and rewrite or revise something. Even up to press time, after more than seven years of research and writing, I was still making changes to the book. My editors Gary Lee Miller and Jonathan Harms will tell you that, and they were a critical part of this process as well making the book the success that it is.

Besides any difficulties, the project was also a lot of fun. The best moments were the writing days, and, dare I say, the rewrites. On the days I had to scan images, use Photoshop, or do organizational or administrative tasks, I hated it and tried to avoid it. I felt like I was wasting my time. I wanted to be back inside the text, not outside of it. If I went for even one day without writing something, I went into withdrawal and I felt a sense of guilt.

The images were a different story. Compared to the text the process was a little easier, but it was also a never-ending process. I am still coming across images today that could have or should have been in Volume One, but they aren’t. The biggest difficulty with the images was the editing process and deciding which images were going to go into the book and which ones were not. Even though the book already has over 1200 images, there are probably an equal number of images that didn’t make it into the book. This was due to space restrictions, and also because too many images could weaken the chapters and dilute the text. Many people see the book as a photo book, or appreciate it on that level, but it can stand on its own as a text book. It could have easily been published without any illustrations, but as a history book, the images were critical in telling the story, because skateboarding and its history are also visual.

We are talking while the Olympic Games are taking place in Río: What do you think about skateboarding has become an Olympic sport?

There has been lot of debate about skateboarding being in the Olympics, and in particular within the core skate community. A number of skaters feel that the Olympics will ruin skateboarding, or that it doesn’t even belong there. My feeling is it won’t change anything; the Olympics are the Olympics, skateboarding is skateboarding, and competition is competition, whether it is the 2016 VANS Park Series World Championships in Malmö, Sweden, or the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. As far as outside corporate interests and mainstream commercialization goes, skateboarding already saw that back in the late 1990s with the birth of the X Games. What is going to be so different about it this time? Nothing. I don’t think there’s anything negative about skateboarding being in the Olympics. It is what it is, and I remain neutral. If anything, it could bring something positive to skating—although what that might be, I have no idea. We’ll just have to wait and see. If there were one thing I’d like to see with the Olympics, it’s that they would generate a greater public interest in skateboard culture, especially its origins and history.

You are a writer, a photographer and a skater. In which projects are you working at now?

I have a variety of things going on right now. I have mostly been preoccupied with promotion of the current book—you know, book signings, travel, talks, and exhibitions. At the same time I’ve been in discussion with another skater about us writing a new type of skate history book together. I have several other book projects that are also in the draft stage. In addition, there are some potential film projects on the table. Then there is Volume Two of A Secret History of the Ollie, which was written at the same time as Volume One. Volume Two focuses on the 1980s. The text needs some minor rewrites and additional research, especially on the New York street scene, and then the manuscript needs to go through the same extensive editing process that Volume One went through. To do this, I need to lock myself in a room again as I did for Volume One, but I’m not quite ready to do that yet.

I am also involved with the Skateboarding Heritage Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation of skateboarding’s history and culture. SHF is a volunteer-based organization, and I am one of its co-founders. SHF’s focus up to now has been on skatepark preservation, namely the last remaining 1970s-era skateparks. The Bro Bowl in Tampa was our first victory; in October 2013 we got it listed on the National Register of Historic Places, largely due to the efforts of Shannon Bruffett. This listing was historic in and of itself because the Bro Bowl became the first structure related to skateboarding and skate culture to ever get recognized by a U.S. government agency. What we did with the Bro Bowl opened up doors for more preservation. A year later Rom skatepark in London was listed in the UK as a historic property. More recently, the Albany Snake Run in Western Australia was listed. I was involved with writing letters of recommendation and support for Albany’s nomination, and A Secret History of the Ollie became an important resource for the preservation authorities in Australia. Besides preservation, we have also been curating and designing site-specific exhibitions on skateboarding and skate culture. There is so much more we’d like to do, including opening up some national and international museums and gallery spaces, but funding is always the issue.

What do you consider to be the most defining characteristics of skateboarding as a culture?

Skateboarding is unique because it has its own community, language, and forms of art—including, of course, the act of skateboarding. Although skateboarding is sometimes referred to as a sport—and that is OK because it involves athletic ability—it is first and foremost a culture. Every culture has a social institution, and for skateboarding one of those located very close to its center has been and continues to be the skatepark. The role the first parks played during the 1970s in creating and developing this culture was crucial, a fact that is discussed in detail in A Secret History of the Ollie. What’s interesting about the community aspect of skateboarding is how it has changed over the years. In the 1960s and 1970s when skateboarding was just finding itself, the community was much more singular and more closely bonded. But today the community is significantly larger, and as a result it has become more diverse. Skateboarding now has subgroups that never existed before. Skateboarding has also unknowingly taken on the mission of changing the world. Because skateboarding by default transcends politics, race, religion, and language, it could be the very thing that will end terrorism and world wars. If new generations across the world are introduced to skating, we might see some real change in the world. This could also be a reason why perhaps skateboarding in the Olympics could be a really good thing.

When you think of a trick, you rarely think about the technology that made it possible. What was the technological key that allowed the invention of the Ollie?

The first thing that comes to my mind is the kicktail, but also critical were the urethane wheel and the precision bearing. And let’s not forget about grip tape! In addition, there was the skatepark, which, during the 1970s, became the crucial laboratory for experimentation and for the development of modern skating. Skateparks were where the Ollie and so many other moves were created, and most it happened during this Golden Era.

If you look back, from the ’70s till now, you see that the evolution of this sport has been meteoric. Do you think it will continue to evolve at the same pace?

That’s a difficult question. The most evolutionary or meteoric decade was without a doubt the 1970s. It was explosive. You have to remember that everything was being done for the very first time during this era, and every piece of equipment we use today was also being invented then. Change was happening at such a rapid pace in the 1970s that every year, in evolutionary terms, was like a decade. An impossible move one month was being done the very next month. By the 1980s modern skating had been born, and with it, all the technology and basic maneuvers that were needed. In the 1980s skateboarding saw more progression, with the Ollie beginning to play a heavier role during that decade. That move, of and by itself, completely evolved skating. The 1980s were explosive mostly because the terrain that skaters rode was being redefined. The 1990s continued where the ’80s left off. Some people might say that today everything that could be done on a skateboard has been done—at least from a foundational perspective—and that what we’re seeing now and have been seeing for some time has been the repurposing of moves and the creation of new combinations and variations. New skaters are bringing back moves that people have forgotten about—or reinventing something that has been invented before, because they never saw it before but imagined it and then decided to do it. So perhaps the answer to your question is that skating continues to evolve every day and will never stop evolving, if only on an individual, personal level.

A book like this one is born out of the love for a culture. What has skateboarding brought to your life?

Skateboarding gave a lot to me when I was growing up, and I wanted to give something back. For me, the best way to do that was to honor the pioneers, especially those who until now have been largely unknown or unrecognized. As I said before, skateboarding was a movement. It was a collaborative effort, and there are many who deserve some kind of place in history.

A Secret History of the Ollie was indeed a passion project, but I have only ever thought of it as a book; however, some people have been calling it a work of art. The first time I heard this was on my first tour when I was in Newport, Rhode Island for a book signing at Water Brothers. The first words out of the mouths of Sid Abbruzzi and his lovely wife Danielle were that A Secret History of the Ollie was art. That stopped me in my tracks. Sid is like the Don of the Northeastern surf and skate scene, so anything that comes out of his mouth is like the word of God. I would have never considered it as art, but perhaps the passion I put into it is very transparent. So maybe it is art, or maybe it is a poem, a poem to skateboarding; an ode to skateboarding and the birth of modern skating.

We’ve evolved from skating barefoot with rudimentary boards to skate in skateparks designed by architects. What do you think of the Street League spectacle?

I don’t have any opinion on the Street League because I haven’t been following it and I don’t know much about it. But to echo what I said earlier, things are what they are; skateboarding is skateboarding, and competition is competition.

Could you tell us a few words about the reception of your book by the audience?

The reception for A Secret History of the Ollie has been nothing short of amazing. I have been staggered by the praise it has gotten from everyone who has picked it up, including readers who knew almost nothing about skateboarding and skate culture in the first place. Some people have even referred to the book as the bible of skateboarding.

For some, the book has even been an emotional experience. During one signing I had one guy walk away from me in the middle of a conversation because he was on the verge of tears. He was not an old-school dude but a younger guy whose father had skated during the 1970s. He had heard some stories, but had no idea of the history or any of the geography. The book gave him access to all that in a complete way and a historically reverent way. It transformed his way of thinking of who he was and where he came from. He now felt in some way he was part of that history or heritage, if only by association, and he felt blessed. I know that sounds corny, but that really happened. Then there was the book signing in Philadelphia where one guy decided to pull out a ring and make a wedding proposal. But not to me!

All the praise for the book was a surprise, though, because I had no idea what people were going to think of it by the time it got into print. After more than seven years of working on the project, I had certainly lost some perspective toward the end, even though I had been guiding it very carefully every step of the way. When I received the first copy off the press, my heart dropped. I kind of thought I overdid it and maybe I’d completely missed the mark. But since its release, it seems to have hit the mark on every level intended from the very beginning when it was just a concept in my head.

Besides the great public reception, the book has won five book awards, including three gold medals and one award for being one of the best photo books of the year, even though it really driven by the text and the story it tells.

Skateboarding is more than a sport, it´s a culture. Skaters have their own look and they even have changed fashion itself. In your book you write that in the skate press of the late ’70s, image was everything. What do you mean exactly?

I think you are referring to the beginning of Chapter 33, “Media Magnet.” In that context, it means the hottest photograph was the photo that was going to make it into the magazines. For photographers and skaters alike—unless they had some personal connections—this was the only chance they had to get themselves into print and into the bible of skateboarding at that time, which was SkateBoarder magazine. The more outrageous the move, or the more outrageous the photograph, the better the chances were for some so-called fame and fortune. In some cases, that radical move may have been something the skater didn’t even land, but in the 1970s all of that was fair game. It was as much about possibility as actual fact. Landing the moves wasn’t what was selling the magazines, images are what sold the magazines, and that is even truer today than it was back then. But today, skaters have to land the trick. Out of context, that statement could be taken as a controversial perspective of skateboarding’s shift to commercialization, whether from the industry side of things or the editorial decisions made by the magazines.

Alan Gelfand was the man who finally invented the Ollie, the trick that changed everything. Do you think any other skater could have done it instead of him? Can you tell us some anecdote about this charismatic skater?

There has been a lot of debate about who did the first Ollie. When people first heard about my project, I was approached numerous times by others who told me they were the first, before Gelfand, or before the Ollie became famous. Some of these moves were no-handed airs, not Ollies, and there is a difference; an Ollie is a no-handed air, but not all no-handed airs are Ollies, so I spent some time in the book making that distinction very clear as the story unravels. Also, the Ollie did not happen instantly, as some people think. It was a process that took approximately eight months from the birth of the Ollie Pop in 1977 to the full-fledged Ollie Air in 1978—and it was a collaborative process involving not just one person but several, a group I refer to in the book as the “Hollywood contingent.” The debate about who did the first Ollie usually centers on three South Florida skaters: Alan “Ollie” Gelfand, Pat Love, and Jeff Duerr, and that is in the book. But the beginning point for everything that happened was the Ollie Pop, and that was Alan “Ollie” Gelfand.

There are too many stories about Alan Gelfand that could be told. A number of them are in the book, and many of them involve some sort of mischief. He loved pranks and good jokes. People remember him for that kind of activity as much as the Ollie. The one thing that stands out about Gelfand is that after he became famous he never forgot his roots. When he traveled he always looked for an up-and-coming skater who had nothing and then gave them some equipment or tried to help them with their skating. If someone was really good but showed too much of an ego, he wasn’t interested in them. Gelfand came from an underdog background, and that was exactly the type of skater he tried to lift up when he became famous and was given that opportunity.

Could you name two or three skaters that in your opinion have the best ollie? Do you know Aldrin Garcia?

Well, the first three that come to mind would have to be Alan Gelfand, Alan Gelfand, and Alan Gelfand. Why? Because when it came to Ollies he had an unmatched style and did them so fluidly with remarkable grace and ease. Then there is David Z, who followed after Gelfand. But this is if we are strictly talking about Ollies on vert, or Frontside Ollies. If we broaden this to include flatground and street, then fingers seem to be pointing in the direction of popular figures like Natas Kaupas and Mark Gonzales, both of whom are a significant part of Volume Two. Aldrin Garcia is a world record holder for the highest Ollie, and not to demean this talented skater or his skill, but what he did was more of a stunt than a style move. The so-called best Ollies should possess style in addition to technical ability. What would be nice to see is a contest for the most stylish Ollie instead of the highest one or longest one. That would be something different.

Iain Borden, author of “Skateboarding, Space and the City”, said about your book: It is amazing detective work and a great value. Did you felt like a detective during the writing process?

Absolutely. From establishing dates of photographs to finding missing persons, and from creating a timeline that hadn’t existed before to establishing some critical historic dates, I certainly had to be a detective. It was also one of the things that made this project so fun. I think I also have a certain knack for detective work, too. Alan Gelfand will occasionally send me a photo of himself from back in the day and ask me when it was taken. I look at the equipment he is riding, what he is wearing, what kind of helmet he has on and its color, and usually can tell him within several months when the image was taken. That ability and knowledge were critical to piecing together the history that I had to for this book. I began the book without any reference points other than a few contests that had been published in the magazines. I had to build this story and timeline from the ground up, beginning with almost nothing, and this is why the project took so unbelievably long. Volume One covers approximately seven years of history and took over seven years to complete. That’s like writing the book in real time.

Surf and skate are inseparable. Which discipline do you think is more beholden to the other?

As it is said for some relationship statuses on Facebook, it’s complicated. Surf and skate were really only inseparable for a brief period, from the 1960s to the 1970s, then they separated again. Prior to the 1960s, skating was an urban street activity developed on roller skate wheels in larger American cities and surfing was an ancient art form that emerged from Polynesia. Their coming together, though, was fortuitous and a marriage made in heaven. In what perhaps might be a really bad analogy, they are lovers who share a house, but who maintain separate bedrooms. They are each very independent of each other, but influenced by one another in many ways. Initially, it was surfing that influenced or dominated skating, but now that has completely shifted around to where skating has influenced how some surfers approach waves and ride their boards. I wish they were inseparable, because surfing really does add an important dimension to skating that is lost upon the street skating crowd of today. Nonetheless, there are still surfers who skate, and skaters who surf, or those who do both equally well. No matter what you do, or what you prefer, style is everything. That is the one thing that has come from surfing that remains inseparable.

www.olliebook.com