{ ENGLISH BELOW }

Los documentales que hablan de los orígenes de la escena del punk y hardcore norteamericano son muy tramposos, puesto que la documentación existente es muy dispersa y, muchas veces, sensacionalista. Sí, los conciertos daban miedo y ser punk significaba ser un outsider social, sin olvidar que la administración de Ronald Reagan era un desastre total. Pero el mundo tampoco parece haber mejorado demasiado en 2015. Puede que las marcas ganen más millones gracias a explotar el punk-rock, aunque todavía no hay nada normal en ir a un club, saltar por todos los rincones, chillar y golpear a desconocidos durante unas cuantas horas, además de pagar por hacerlo.

“A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90)” habla sobre una escena que tenía un ADN totalmente distinto que el resto de lugares que vieron nacer este género musical en los Estados Unidos. Antes de que internet homogeneizara cada zona del país, el ambiente social, las estructuras gubernamentales, el clima y la economía para que los jóvenes punks vistieran, sonaran y actuaran igual que el resto. Los directores del documental (Scott Crawford y Jim Saah) ponen de relieve las únicas circunstancias que hicieron de DC un lugar tan genuino, ecléctico, vital e influyente, además de contar la historia de una década a través de los personajes que lo vivieron desde primera línea de fuego.

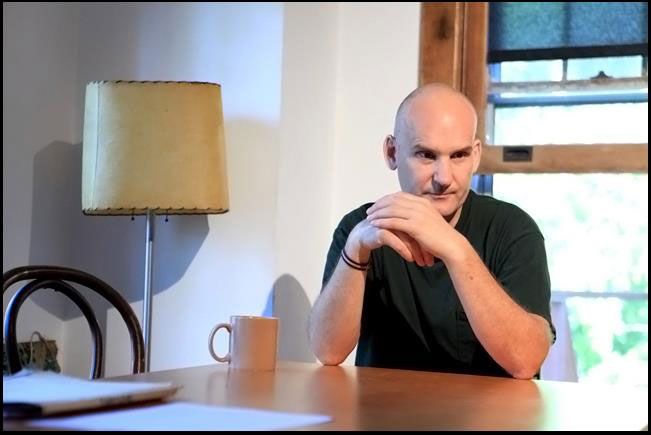

Además, Crawford fue el creador del magazine Metrozine, que se centraba en la escena de DC de principios de los años 80, por este motivo está perfectamente familiarizado con ese movimiento y es capaz de usar las anécdotas de Ian MacKaye, Jenny Toomey, Bobby Sullivan, Dante Ferrando, J. Robbins, John Staab y otras estrellas de aquella ciudad para contextualizar lo que significaron y lo que aún significan actualmente aquellos “salad days”. Hemos tenido la oportunidad de charlar con él para saber cómo logró producir esta película y dar sentido a una historia tan compleja y fascinante.

Fugazi

¿Crees que el hecho de haber crecido en DC tuvo una influencia especial en tu vida y en tu carrera?

Creo que me dio la confianza y el valor para buscar y perseguir las cosas que realmente tenían un significado para mi. Piensa que he pasado más de un tercio de mi vida documentando la música y la cultura independiente.

¿Cuál crees que es el gran malentendido sobre la escena de DC y cómo lo trataste en el documental?

Creo que el mayor malentendido sobre la escena punk del DC de los años 80 fue el mito del “straight age”. No todas las personas seguían ese estilo de vida y nadie los miraba mal por eso.

Jeff Nelson dijo que la escena de DC estaba muy documentada, incluso más que la de Boston, New York y otras ciudades porque la mayoría de chavales se podían permitir cámaras de video o tenían parientes que trabajaban en periódicos. Esto hizo que hubiera una idea de preservar lo que sucedía. ¿Crees que es cierto y, en caso de serlo, podemos decir que favoreció la producción del documental?

Creo que es completamente cierto porque DC es una ciudad invadida por los medios de comunicación. Hacer reportajes, documentar lo que sucede y preservar la información es parte de la cultura de aquí. A pesar de todo, me gustaría que hubiera un archivo más grande del que hubiéramos podido sacar imágenes… pero estamos hablando de los años 80, cuando nadie tenía teléfonos móviles.

Por curiosidad, ¿qué partes tuviste que omitir de todo el material de archivo que recopilasteis para el documental?

Hubo muchas partes de entrevistas y algunas bandas que no pude meter en los 100 minutos que dura el documental. No sabría decirte si hay algún fragmento de material rodado que lamente no haber incluido.

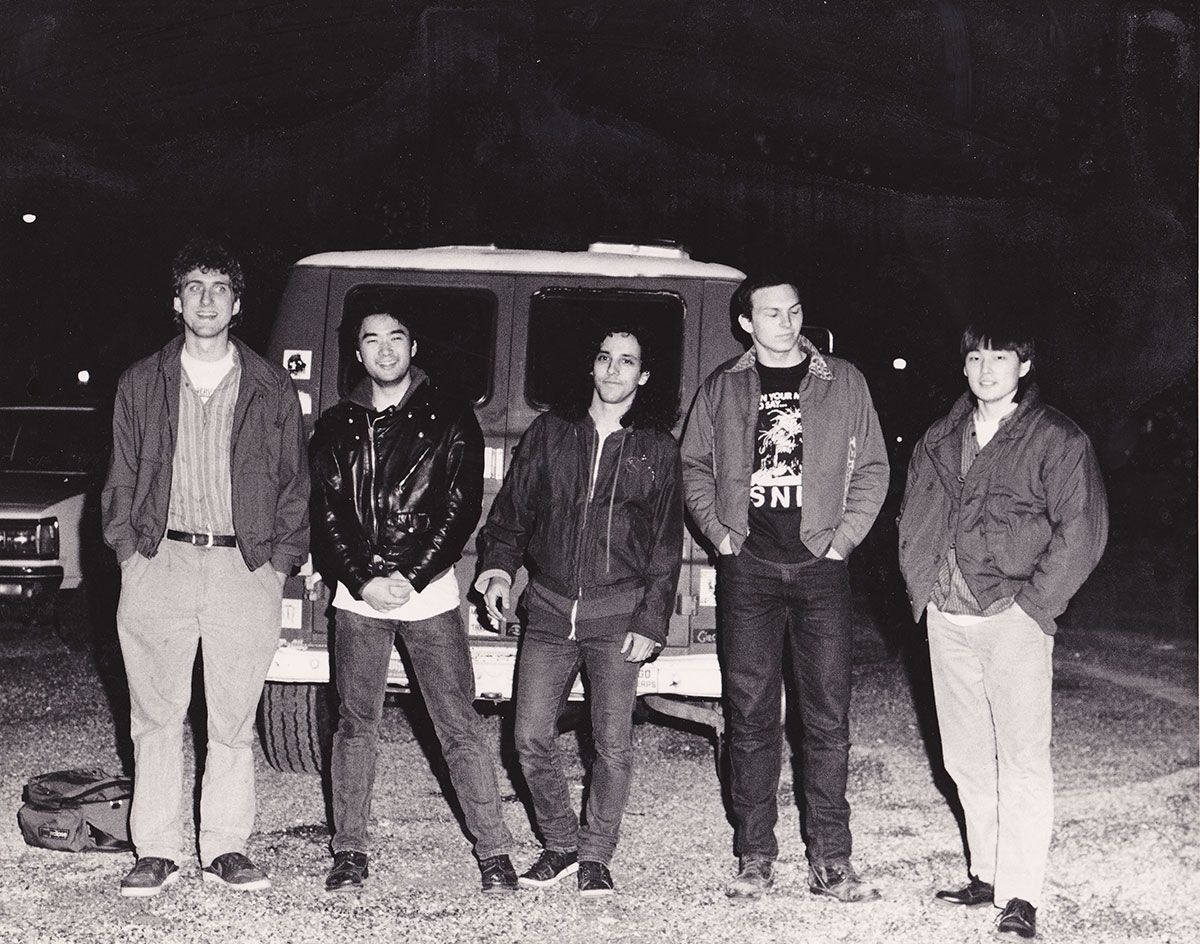

ph: Fred Nye

¿Puedes contarnos por qué elegiste ese estilo narrativo y ese marco temporal para “Salad Days”?

Fue un período esencial para mi (y para muchos otros) y se trataba de algo de lo que no había escrito desde los años 80. Recuerdo cuando mi hijo cumplió 12 años (la misma edad a la que yo empecé a ir a conciertos de rock) y en seguida supe que necesitaba documentar aquel momento de mi vida para él y también para el resto del mundo.

La parte que se centra en los inicios del “straight edge” explica que es tanto un acto de abstinencia como una manera de organizar conciertos para todas las edades. ¿Crees que ambos factores fueron igual de relevantes?

Creo que la política de organizar conciertos para “todas las edades” que instauró gente como Ian MacKaye realmente iban mano a mano con la filosofía “straight age”. Lo que está claro es que todo giraba siempre alrededor de la música.

Dado que los fundadores de la escena de DC se dejaron llevar por otros intereses, avanzaron hacia otros territorios o dejaron de hacer música, ¿crees que los que vinieron después mantuvieron el mismo espíritu y la tradición?

Claro que sí. Creo que el espíritu original sigue muy vivo actualmente en DC. Aquel estilo musical se ha convertido en algo tan emblemático como la mismísima Casa Blanca.

¿Por qué crees que la música de DC estaba tan preocupada por los temas sociales y la política?

Creo que se trataba del hecho de que la sede del gobierno de los Estados Unidos se encontrara en nuestro patio trasero. Allí se toman cada día decisiones que nos afectan a todos, por este motivo la ciudad es el centro de todas las protestas políticas del país. Es importante recordar que la mayoría de los padres de los miembros de esas bandas de punk eran abogados, oficiales de alto rango o miembros de lobbies. Y para nosotros era normal oponernos a eso y discutir sobre temas políticos.

La escena de DC siempre se ha retratado como un movimiento serio, aunque el documental también está repleto de humor y autoconciencia. ¿Quién crees que eran los artistas más divertidos que entrevistaste?

Éste es uno de los grandes malentendidos sobre esa época, puesto que mucha gente decía que la escena no tenía humor y que se tomaba a si misma demasiado en serio. Puede que hubiera elementos que sí que encajaran en esa definición, pero también había muchos otros que no lo eran y me interesaba mucho mostrar esa otra faceta.

Aunque es un relato fantástico para aquellos que tienen una relación personal con el tema, ¿qué crees que verán los más jóvenes o los que no conocen la escena del DC?

Creo que, a fin de cuentas, es una película sobre el poder de la comunidad y la fuerza que surge de tus convicciones personales. Todo el mundo puede identificarse con ello.

Void, 1983

Scream, 1983

Nation Of Ullyses

Minor Threat, 1983

Marginal Man

Marginal Man

J Mascis

Iron Cross

Ian Mackaye

Fugazi

Faith

Dave Grohl

Black Market Baby

(ENGLISH)

US hardcore punk documentary films that cover the origins of the scene are tricky, as the original documentation is often sparse and sensationalist. Yes, the shows were scary, and being a punk meant that you were an outlier in society. Not to mention that Ronald Reagan’s administration was a hot mess. But the world doesn’t seem much friendlier at all in 2015. Sure, there’s more profit to be made of punk rock, but there’s still nothing normal about going to a club, jumping around, screaming, slamming into strangers for a few hours, and paying for it.

“A Decade of Punk in Washington, DC (1980-90)” covers a scene that had a completely different DNA than most of the flashpoints in the United States, just before the Internet homogenized each region in the country, the social climate, governmental structure, weather and economy factored into just what these young punks were going to look, sound and act like. Filmmakers Scott Crawford and Jim Saah’s documentary highlights the unique circumstances that made DC so genuine, eclectic, vital, and influential; and tells the story of a decade through many of the personalities who were in the driver’s seat.

Crawford himself started a zine called “Metrozine” that covers DC in the early ‘80s, so he’s steeped in the narrative and able to use the anecdotes of Ian MacKaye, Jenny Toomey, Bobby Sullivan, Dante Ferrando, J. Robbins, John Staab, and other DC luminaries, in order to contextualize what those salad days really meant and still mean to this day.

So were all the DC kids really affluent and entitled, or even “nerds” as Brian Baker calls them in the documentary? Here’s what Crawford said about the film and the process of creating it.

How did growing up in the DC scene impact you later in life and your path?

I think it gave me the confidence and the permission to pursue the things that meant the most to me. I’ve spent more than a third of my life documenting independent music and culture.

What did you see as the biggest misconception about the DC scene and how did you reflected it on the documentary

I think the biggest misconception about the DC punk scene in the 80s was the straight edge myth. Not everyone here was straight edge, and conversely, those people that weren’t straight edge were not ostracized.

Jeff Nelson once said that DC’s scene was heavily documented–much more so than Boston, New York, etc–because many of the kids could afford to do so and/or had parents who were working for newspapers, etc, so there was an appreciation for preserving it. Did you find this to be true and if so, did it make it easier for you to put together Salad Days in any sense?

I think it’s absolutely true. DC is a media town. Reporting, documenting and preserving information is a part of the culture here. Having said that, I wish there was a bigger archive that we could’ve pulled from—but we’re talking about the 1980s. Nobody had cellphones back then.

What were the hardest parts to omit of all the footage you amassed?

There were so many great quotes and bands that I couldn’t fit into 100 minutes. I’m not sure if there’s any ONE bit of footage that I regret not putting into the film though.

Can you explain why did you choose that narrative and timeframe for Salad Days?

It was a pivotal time for me (and countless others) and something I’d never written about since the 80s. I remember when my son turned 12 (the age I was when I started going to punk rock shows) I knew that I needed to document that period of time in my life for him—and the rest of the world.

The section in the film that talks about the origins of the “straight edge” philosophy implies that this is as much about abstinence as it was a kind of loophole to throw “all ages” shows. Do you feel both factors were important? Why?

I think the “all ages” policy that folks like Ian MacKaye were able to lobby to put in place certainly went hand in hand with the “straight edge” philosophy. It was always about the MUSIC.

As the founders of the DC scene pursued other interests, moved, or ceased to play music, did you feel that those who picked up kept that spirit and tradition?

Sure. I think that original spirit is still very much alive even today in DC. It’s become just as much of the musical aesthetic as the White House.

Why do you think that music in DC was so attached to global issues and politics?

I think it was the fact that the seat of government was in our backyard. Decisions that affect everyone were being made daily —we’re the center of protest and political discourse here. It’s important to remember that many of the band members’ parents were lobbyists, lawyers, and high ranking officials. Discussing social and political issues were a part of their daily routine.

DC’s been portrayed as serious, but there’s plenty of humor and self awareness in “Salad Days”. Who do you think was the funniest artist from the personalities you interviewed?

That’s one of the many misconceptions about that period—that the scene was humorless and took itself too seriously. I think there elements of the scene that may have been both of those things, but there were certainly plenty of others that weren’t and it was important for me to show that.

While it’s a fantastic capsule for those who have a personal attachment to the subject, what do you hope those who aren’t aware of the history of DC’s scene or young viewers will take away from Salad Days?

I think ultimately it’s a film about the power of a community and the strength that comes from your personal convictions and sticking to your guns. Anyone can relate to that.

www.saladdaysdc.com