La realidad depende del punto de vista desde el que se miran las cosas que nos rodean. Si damos por sentado aquello que tenemos al alcance de la mano, corremos el riesgo de quedarnos estancados y de dejar escapar oportunidades irrepetibles. No se trata de ser rebelde y oponerse a las normas por el simple hecho de llevar la contraria, sino que el secreto consiste en tener curiosidad y querer descubrir qué se esconde detrás de lo evidente. Muchas veces esta curiosidad no es fingida ni impostada, sino que surge a raíz de los acontecimientos que marcan el pulso de nuestra vida cotidiana y puede convertirse en un estilo de vida fascinante. Seguramente esto es lo que debe pensar John Witzig, porque sin pretenderlo se convirtió en el mayor cronista del auge del surf en Australia a principios de los años 60 y sus fotografías siguen transportándonos a lugares tan remotos y mágicos que parece que sean un sueño. Su historia nos demuestra que las mejores cosas de la vida nunca se planean, puesto que logró unir su pasión por las cámaras y su amor por las olas en un momento en el que la prensa alternativa empezaba a florecer en las Antípodas y el ambiente era especialmente propicio para que jóvenes con talento (y mucha curiosidad no pretendida) pudieran desarrollar una carrera inimaginable a ojos de sus padres. Si a la brecha generacional de aquella época le sumamos el auge de la contracultura, la estética psicodélica, el activismo medioambiental y las ansias de construir uno mismo las cosas que nos apasionan, es evidente que nos encontramos delante de una persona que ha trascendido su faceta profesional para alzarse como uno de los grandes iconos del surf moderno. Hemos tenido la oportunidad de conversar con John Witzig para conocer sus experiencias a lo largo de seis décadas a pie de playa, adentrarnos en sus viajes antes de la comercialización de las olas y descubrir qué esconden sus instantáneas más emblemáticas. Puede que su último libro editado por Rizzoli en Nueva York sea una joya de coleccionista, pero la verdadera esencia de su legado está en sus palabras.

Tengo entendido que naciste en Sídney, pero que te criaste en un pueblo cerca de Palm Beach. ¿Cómo era la vida en Australia en aquellos días y qué recuerdos tienes de la escena del surf de finales de los años 50?

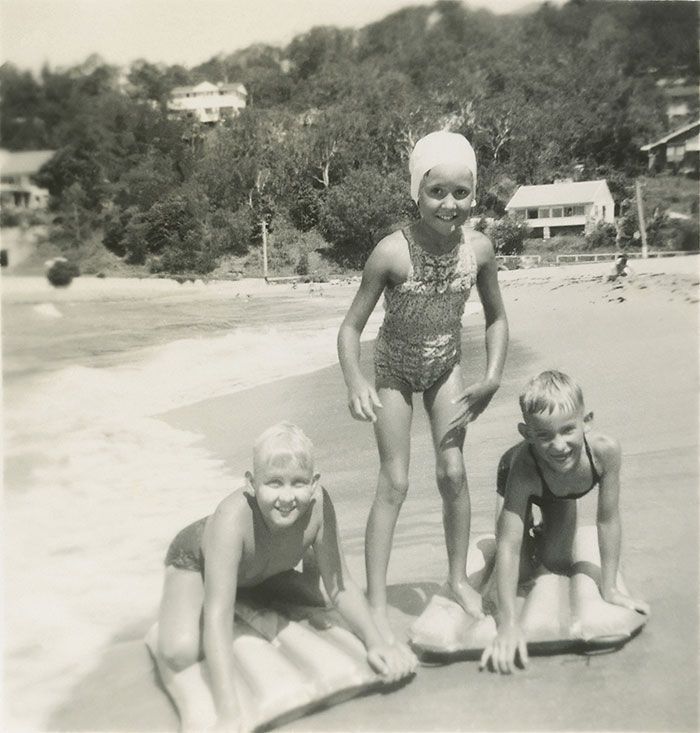

Vivíamos en una zona interior, alejados de las playas del norte de Sídney, pero éramos afortunados porque mis padres tenían una casa cerca de Palm Beach donde fuimos hasta que fui adolescente. Pasamos muchas vacaciones allí y esas experiencias me marcaron para el resto de mi vida porque me encantaba todo lo relacionado con el océano. Hasta finales de los años 50, los australianos practicaban surf con unas tablas de madera contrachapada y eran horribles. Entonces, en 1956, llegaron los socorristas norteamericanos con unas tablas hechas de balsa, con quillas, más pequeñas y ligeras. Sin embargo, pasaron varios años hasta que ese material estuvo disponible en nuestro país. Mis primeras dos tablas fueron réplicas de contrachapado de un modelo llamado Malibú porque los socorristas venían de California… realmente eran horribles.

With my brother Paul (left) and my sister Diana at Palm Beach c. 1950

Muchas veces se comenta que en Australia hubo una gran relación entre los primeros surfers y los clubes de salvamento marítimo…

Muchos australianos que estaban interesados por el surf se hicieron miembros voluntarios de los Clubes de Salvamento porque tenían unas casetas donde podían quedarse y eso era una gran ventaja en una época en la que los coches no eran tan habituales, sobre todo entre los jóvenes. Durante la primera mitad de la década de los 60, los coches fueron más accesibles y las tablas se volvieron más pequeñas y ligeras. Eso hizo que los clubes de surf perdieran popularidad. Sin olvidar que el autoritarismo y la misoginia que imperaba en esos clubes también iba en contra de los aires que se respiraban en aquella época.

¿Podrías contarnos cuándo empezó realmente tu afición por la fotografía? Seguramente fue gracias al apoyo de tus padres…

Al cumplir 10 años, empecé a hacer fotos con una cámara Box Brownie de segunda mano que heredé, aunque no puedo afirmar que las imágenes fueran buenas. Cuando fui adolescente, me interesé en las increíbles fotos en blanco y negro que aparecían en revistas europeas y americanas. En seguida, esas publicaciones y los fotógrafos se convirtieron en uno de mis mayores intereses… y eso, curiosamente, coincidió con la aparición de las primeras revistas de surf australianas.

En aquella época, ¿tuviste la oportunidad de ver los documentales de surf que rodaban directores norteamericanos como Bud Browne, John Severson y Bruce Brown?

Las películas de Bud Browne fueron las primeras que vimos en 1958 porque las proyectaba Bob Evans, el primer emprendedor del surf australiano. También vi mi primera tabla de balsa en la proyección de uno de esos documentales en el Whale Beach Surf Club. Fue una época excitante porque descubrimos el surf que se hacía en ese momento en California y las grandes olas de Hawái… entonces hubo muchos primeros descubrimientos.

¿Qué recuerdos tienes de las proyecciones de aquellos documentales de surf ahora considerados legendarios?

Algunas de aquellas películas estaban narradas en directo. Sin duda, recuerdo a Bruce Brown haciendo ese tipo de proyección un tiempo después, pero ahora no tengo presente si eso sucedía con los documentales de Bud Browne. Vi la mayoría de las primeras películas en Sídney y entonces se reunían los surfers de diversos pueblos. Era un gran acontecimiento.

Empezaste a escribir artículos para la revista Surfing World en 1963. ¿De dónde venía tu interés por el periodismo y qué pretendías con aquellos reportajes?

Siempre me había gustado leer, así que escribir no parecía tener ningún misterio. El primer artículo que publiqué en Surfing World era bastante malo, igual que el resto de lo que sacaban. En mi defensa te diré que me pareció darme cuenta de mis errores y pude mejorar. La década de los 60 fue una época en la que, sencillamente, sentíamos que podíamos hacer cosas… tanto si teníamos la formación adecuada como si no la teníamos. Fue un período genial para los verdaderos amateurs y entonces yo seguía pidiendo cámaras y teleobjetivos para hacer fotos.

Rodney Sumpter at Wategos c. 1962

En tu polémico artículo titulado “We’re Tops Now” de 1967 aclamabas a una nueva generación de surfers australianos que, por primera vez, superaban a los de California…

Tenía dos motivos principales a la hora de escribir ese artículo para Surfer magazine. Primero, que la victoria de Nat Young en el San Diego World Championships de 1966 estuvo totalmente ignorada por parte de las grandes revistas americanas. Siguieron publicando los mismos temas autocomplacientes de siempre. Segundo, yo estaba suficientemente metido en lo que sucedía en la escena del surf australiano para darme cuenta de que “algo” estaba cambiando y que ese “algo” podía ser importante. Más tarde se vería como el inicio de la revolución de las tablas cortas. Bob McTavish, George Greenough y Nat Young, los tres protagonistas principales, eran amigos míos. Reconozco que fui deliberadamente provocativo en ese artículo y exageré las cosas, pero creo que fue necesario. Puede que no convenciera a nadie en los Estados Unidos, pero sí que se hicieron eco del artículo. Y, poco después, fue imposible que ignoraran las imágenes de Honolua Bay tomadas en diciembre de 1967.

Headless McTavish 1966

Tu hermano Paul se convirtió en un icono del cine de las olas gracias al documental “Evolution” que rodó en 1969. ¿Qué recuerdos tienes de aquel rodaje y de la gente que participó?

La influencia de las películas de mi hermano empezó un poco antes que el estreno de “Evolution”. La secuencia final de su previo documental, “The Hot Generation“ ya mostraba las imágenes básicas de Nat Young y Bob McTavish con sus tablas V-bottom en Honolua. En su enciclopedia del surf, Matt Warshaw dice que ese título “contribuyó a presentar al mundo entero las enormes posibilidades de las tablas cortas”. Por lo que se refiere a “Evolution”, solamente tienes que fijarte en los protagonistas: Nat, Ted Spencer y el extraordinario Wayne Lynch, que sólo tenía 16 años. Wayne cambió el mundo del surf de una manera más profunda que cualquier otra persona que haya visto. “Evolution” mostró todas esas cosas al mundo y tuvo mucha repercusión.

Wayne Lynch at Whale Beach 1968

La escena del surf de finales de los años 60 estaba estrechamente relacionada con la contracultura y la psicodelia ¿Crees que los surfers, los artistas o los fotógrafos tienen que mostrarse como rebeldes para ganar notoriedad??

Bueno, puede que todo lo que sucedía a finales de los 60 y durante los 70 estuviera influido, en cierta medida, por la contracultura… incluso si se trataba, simplemente, de rechazarla. En la versión de Australia que yo experimenté, estaba estrechamente relacionada con el surf. En aquella época, el país se involucró en la Guerra de Vietnam y la desconfianza hacia el gobierno no se limitaba únicamente a los jóvenes. Tengo la impresión de que muchos surfers son espontáneamente antiautoritarios puesto que el escepticismo es una cualidad muy útil que debes tener siempre presente.

Que Australia mandara tropas a la Guerra de Vietnam es un hecho poco conocido en otros países. ¿Participaste en las manifestaciones o en las marchas antibelicistas?

Yo estudiaba en la Universidad de Sídney cuando las protestas contra la Guerra de Vietnam llegaron a su punto álgido en 1971. Recuerdo que las clases cambiaron de horario para que pudiéramos ir a las marchas. Ten en cuenta que en Australia nunca se habían visto protestas de esta magnitud. Logramos cerrar los centros de las mayores ciudades y ningún otro tema logró radicalizarme del modo que éste lo hizo. Sinceramente, no pensaba que los gobiernos nos pudieran mentir de esa manera.

¿Podrías explicarnos cómo surgió Tracks magazine? He leído que la fundaste en 1970 junto a Alby Falzon y David Elfick…

Yo había trabajado de editor en una revista llamada Surf International y me despidieron. Albe trabajaba para Bob Evans en Surfing World y tenía pensado rodar una película. David trabajaba en un periódico pop y tenía una amplia experiencia en el mundo impreso, cosa que tanto Albe como yo no teníamos. Yo necesitaba un trabajo, Albe quería un medio para promocionar su documental y David tenía suficiente entusiasmo para organizar dos proyectos al mismo tiempo. El resultado fue un tabloide llamado Tracks, que era radicalmente distinto de las revistas de colores brillantes de la época. Además, el contenido editorial también se fijaba en temas sociales y medioambientales, además de tener el surf como eje central. Éramos vulgares y rudos, pero fue un éxito inmediato.

Gracias a tu trabajo como fotógrafo y periodista tuviste la oportunidad de recorrer el mundo entero. ¿Qué recuerdos tienes de tu visita a Portugal en 1976? Seguramente encontrasteis buenas olas y poca gente en las playas…

Pasé 8 meses en Europa en 1976 junto a un amigo australiano llamado Mark Allon y visitamos por primera vez Portugal. No teníamos coche, así que andamos hacia el norte de Ericeira para encontrar un break del que habíamos oído hablar mucho. Llegamos a un sitio que creímos que era Dos Coxos, pero había poco oleaje. Esto me recuerda que las aventuras de surf no solamente tratan de encontrar olas. Volví a Europa en 1979, esta vez con un pequeño Citroën y con la esperanza de encontrar buenas playas. Salí de Guetaria, en la costa francesa, sin que hubiera ninguna ola. Entonces seguí mi ruta por el norte de España. Había visto fotos de Mundaka que me habían cautivado, pero estaba completamente plano cuando llegué. En Portugal volví a Dos Coxos y, finalmente, había buen oleaje… y, posiblemente, esas fueron las mejores olas que cogí en Europa.

Mark Allon at Dos Coxos 1976

Dos Coxos 1979

¿Te impresionó alguna cosa de tu ruta por el norte de España?

Recuerdo principalmente el paisaje… las interminables colinas con olivos, como si se tratara de una enorme pintura abstracta. También recuerdo que unos amigos me llevaron a comer tapas en San Sebastián. En Portugal, recuerdo sobre todo el olor persistente de la gente cocinando sardinas en Ericeira y también el vinho verde. Me encantaron las siempre cambiantes platos típicos y los vinos de Europa. Era un lugar maravilloso para practicar surf.

A lo largo de los años has fotografiado a legendarios surfers australianos y muchos se han convertido en amigos cercanos. ¿Qué puedes contarnos de Bob McTavish?

No puedo negar que creo que Bob fue una figura muy influyente en el desarrollo de las tablas cortas. Entonces yo no estaba interesado en el diseño de tablas y hoy todavía lo estoy menos. Pero la mayoría de mis amigos no dejaban de hablar de ese tema. El entusiasmo que mostraba Bob era contagioso y no solamente en ese tema en concreto.

Bob McTavish with the first Plastic Machine 1967

¿Qué destacarías de tu amistad con Nat Young?

En 1961 hice mis primeras fotos de surf con una cámara y unas ópticas prestadas y ya aparecía Nat con 14 años en su break habitual de Collaroy. Con el paso del tiempo hicimos muchos viajes juntos y es uno de mis grandes amigos. Nat se podría definir como un libertario natural porque cree que debería poder hacer cualquier cosa que le apeteciera. Siempre le ha gustado asumir riesgos y eso no ha cambiado.

Nat at Honolua Bay, Maui 1967

Nat at Collaroy 1961

Uno de mis cineastas de surf favoritos es George Greenough. ¿Cuándo tuviste la oportunidad de conocerlo?

Creo que conocía a George a principios de 1966. Lo que sí sé es que escribí un breve artículo sobre él en el número sobre “New Era” que publiqué en Surfing World y que me encargó Bob Evans en julio / agosto de ese año. George es un personaje fascinante y un surfista que me ha inspirado mucho. Bob McTavish ha comentado que la motivación para la revolución de las tablas cortas se basaba en la idea de fabricar tablas en las que pudiésemos ponernos de pie y con las que cogiésemos olas del mismo modo que George hacía con sus pequeñas tablas. Yo llevaba trabajando mucho tiempo en revistas de surf y veía habitualmente a George. La única vez que viajamos juntos fue a Hawái a finales de 1967 y le vi hacer los trucos más radicales que he presenciado.

Tengo entendido que una de las fotos de las que más orgulloso estás no tiene nada que ver con las olas, sino que se trata de un grupo de amigos en el porche de una casa. ¿Por qué crees que el estilo de vida de los surfers se ha vuelto tan icónico?

Las imágenes que reflejan el mundo que rodea al surf son las que más me interesan actualmente. Son fruto de mi afición natural para documentar el mundo en el que vivía y, por suerte, acostumbraba a llevar siempre la cámara encima. La foto que comentas se titula “A House at Torquay” y forma parte del pequeño conjunto de mis favoritas. El surf era completamente auténtico en aquellos años porque no había ningún motivo que lo corrompiera. Evidentemente, eso cambió y los anunciantes tomaron prestada esa autenticidad para dar credibilidad a los productos que vendían. Yo trabajaba en revistas que jugaron un papel destacado en ese proceso, así que sería hipócrita por mi parte quejarme de todo eso. Con la perspectiva del tiempo, es imposible no pensar que éramos muy ingenuos. No creo que se pueda crear una iconografía, sin embargo, observábamos y capturábamos lo que sucedía a nuestro alrededor. Parece que se necesitan varias décadas para decir si todo eso que capturamos en imágenes estaba bien o mal.

A house at Torquay above, and Arcadia below.

and this is Country soul.

En los últimos años has publicado varios libros con tus mejores instantáneas. ¿Has descubierto detalles que no recordaras o que te pasaran desapercibidos en su momento?

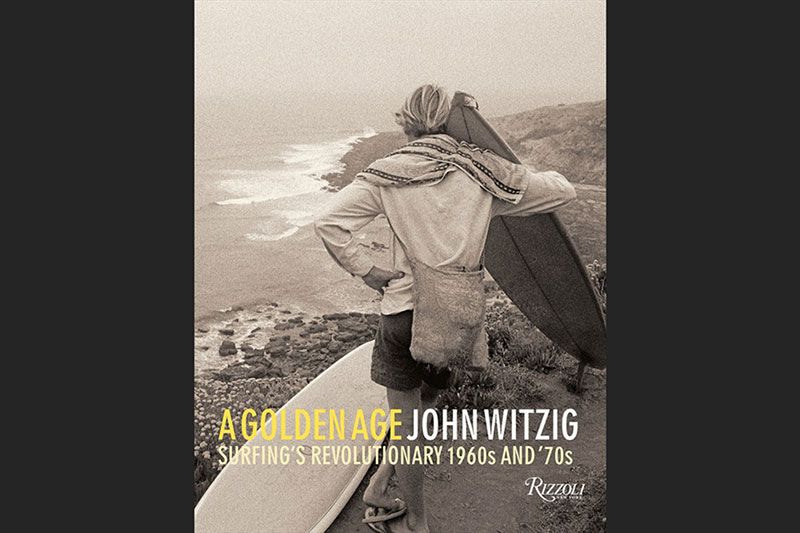

He hecho tres publicaciones, dos de las cuales son libros y aparecieron en un período de 6 años. La primera fue una publicación muy pequeña que financió una galería con la que colaboro en Sídney. Trabajé en el diseño y en la producción de libros ilustrados durante 20 años, así que lo hice todo por mi cuenta. En 2013, la editorial Rizzoli en Nueva York sacó un libro con mis fotos. Hicieron un trabajo precioso y me siento honrado con el resultado porque es lo más cerca que hay de tener una colección definitiva de mis fotos. La verdad es que no he descubierto nada nuevo, sin embargo, el libro de Rizzoli fue muy interesante porque fue producto de una intensa colaboración e hicieron cosas con mis imágenes que yo nunca habría logrado por mi cuenta. Eso me dio nuevas perspectivas y fue una gran experiencia.

Actualmente, mucha gente decide vivir de una manera más sencilla para ser consecuentes con los cambios sociales y el medio ambiente. ¿Consideras que lo que hicisteis en los años 60 y 70 os posicionó como pioneros del activismo?

Esa época influyó en mi vida de una manera muy significativa. Yo no aparezco en esas fotos, pero lo que estaba documentando realmente era mi vida. En el período que va de 1969 a 1970 me gustaba evangelizar a la gente, pero ahora me contento con hacer lo que hago y vivir como vivo. Y si eso influencia a alguien, me parece bien. Y si no sucede, me parece bien igualmente. En noviembre de 1972 empecé a construirme mi primera casa en Angourie con la idea de vivir en un marco natural con la menor interferencia posible con el medio. Hace 10 años terminé la casa en la que vivo ahora y los principios de su construcción fueron exactamente los mismos.

¿Sigues vinculado de algún modo a la cultura del surf?

En absoluto. La mayoría de mis amigos de aquella época siguen siendo buenos amigos y algunos siguen vinculados al surf. Yo simplemente observo desde un lateral.

Para terminar la entrevista, ¿podrías contarnos qué cosas te apasionan actualmente y si la fotografía y los viajes siguen siendo una fuente de inspiración?

Vendo copias de mis fotos a través de mi web y las peticiones para revistas y libros nunca paran. Parece que el interés por la década de los 60 es inagotable. Viajé por Asia durante varios años, aprovechando que iba a Singapur a revisar las pruebas de impresión de los libros en los que trabajaba. Eso me permitió el lujo de visitar algunos lugares maravillosos e hice muchas fotos en esos trayectos. Sin embargo, mis años de viajero se han terminado. Pero no me preocupa porque he visto rincones fabulosos del mundo.

Mark Richards at Haleiwa

Nigel in Western Australia

Freckles at Spooky

Buzzy Kerbox at Haleiwa

Wayne Lynch at Bells Beach

Guethary

Fresh mullet

Nat and the girls

Sunset Beach

Midget Farrelly at Palm Beach 1964

Michael Peterson mid-1970s

English:

JOHN WITZIG.

IN THE ANTIPODES OF SURFING.

Reality depends on the perspective we look the things around us. If we assume all that we have at hand, we take the risk of staying stagnant and missing unrepeatable opportunities. It is not about to be a rebel against the rules just for the sake of being contrary, it is about to be curious for discovering what lies behind the obvious.

Often this is curiosity is not fake or unfeigned and raises from the events that mark the pulse of lives. Surely this are the thoughts of John Witzig, because he became, in an unwittingly way in the greatest chronicler during the rise of surfing in Australia in the early 60s and still his photographs transport us to places as remote and magic that seems to be a unreal. His story shows that the best things in life are never planned, as he achieved to mix his passion for cameras and his love for the waves in a time when the alternative press began to flourish in the Antipodes and the atmosphere was especially friendly for talented young people (and many unintended curious) that could develop an unimaginable career in the eyes of their parents.

If to the generation gap we add the rise of the counterculture, psychedelic aesthetic, environmental activism and desire of buildind things that fascinate us, it is clear that we are faced a person who has transcended his professional role to stand as one of the greatest icons of modern surfing. We have had the opportunity to talk with John Witzig to share their experiences over six decades on the beach, get into his trips before the wave marketing and to discover what hides his most emblematic snapshots. Maybe his last book published by Rizzoli in New York is a gem, but the true essence of his legacy is in his words.

You were born in Sydney and grew up near Palm Beach. How was it living in Australia in those days and how do you remember the surfing scene in the late 50s?

We lived inland from Sydney’s northern beaches, but were fortunate enough to have a holiday house near Palm Beach until my younger teenage years. We spent a lot of holidays there, and that experience marked me for the rest of my life. I loved everything about the ocean. Until the late 1950s, Australians surfed plywood paddleboards… they were horrible things. US lifeguards bought smaller, lighter boards made from balsa with fins to Australia in 1956, but it took a few years for balsa to become available. My first two boards were hollow ply copies of what we called ‘Malibu’ boards because the lifeguards came from California. They were pretty awful too really…

I have read there was a big connection between the first surfers and Surf Life Saving Clubs in those days…

Many Australians who were interested in the surf became members of the volunteer Surf Life Saving Clubs. They had clubhouses where you could stay which was a great attraction at a time when cars were way less common… amongst younger people especially. In the first half of the 1960s, a combination of smaller lighter boards and cars becoming more available made the surf clubs less attractive as an option. The authoritarianism and misogyny of the clubs was also increasingly at odds with the spirit of the times.

When did you passion for photography start? Maybe that was thanks to your parents…

I took some pictures with a pass-me-down Box Brownie when I was maybe around 10-years-old, but I can’t say that I ever took a good picture. As a teenager I became interested in the great black and white pictures that I saw in European and US magazines. Quite quickly magazines and photographs became a serious interest… and that coincided with the launch of the first Australian surfing magazines.

Did young surfers in Australia get to see the surf documentaries coming from the USA by Bud Browne, John Severson and Bruce Brown? How were those screenings?

Bud Browne’s films were the first that I saw in maybe 1958… they were toured by Bob Evans who was the first Australian surfing entrepreneur. I also saw my first balsa board at a showing of one of those films at the Whale Beach Surf Club. Those were exciting times as we were exposed to contemporary Californian surfing and the big waves of Hawaii… a lot of firsts.

How were the surfing documentary screenings in the late 50s? People usually say they were crazy, narrated live and that they were a gathering of surfers from many towns…

Some of the films were narrated live. I certainly remember Bruce Brown doing that a little later, but whether the Bud Browne films were, I can’t remember. I saw most of the early films in Sydney, and there would be gatherings of surfers from quite a wide area. It was a big deal.

You started writing articles for Surfing World magazine in 1963. Where did your interest for journalism come from? What was your aim with those articles?

The first story of mine that was published in Surfing World in 1963 was quite as bad as the general standard. In my defence I do seem to have realised that, and I got better at it. I’d always read a lot, so writing didn’t seem mysterious. The 1960s was definitely a time when we felt that we could simply do things… trained or not. It was a great period for the true amateur… and I was still borrowing cameras and telephoto lenses in the very early years.

Your ‘We’re Tops Now’ article from 1967 has become legendary because it celebrated the new generation of Australian surfers beating the Californians. What was your perception of Australian surfing as opposed to American surfing in those days?

The impetus for the “Were Tops Now” story for Surfer magazine were two. First was that Australian Nat Young’s win in the 1966 San Diego World Championships had been totally ignored by the major US magazines. They just continued to run the same old self-congratulatory stuff. Second, I was close enough to what was happening in surfing in Australia to realise that something was happening, and that that ‘something’ might be important. It would later be seen to be the start of the shortboard revolution. Bob McTavish, George Greenough and Nat Young, the pivotal individuals involved, were all friends of mine. I was deliberately provocative in that story for Surfer… I exaggerated shamelessly, but I’d argue that it was necessary. I may not have convinced one single person in the US, but they did notice the story, and not much later, footage from Honolua Bay in December 1967 would be impossible to ignore.

Your brother Paul became an icon of surf filmmaking thanks to Evolution in 1969. What do you remember about its shooting and the people involved? Why do you think it has become a milestone?

The influence of my brother’s films began earlier than Evolution. The finale of his previous film, The Hot Generation was the pivotal footage of Nat Young and Bob McTavish on their V-bottom boards at Honolua. In his Encyclopedia of Surfing, Matt Warshaw says that it “helped introduce the surfing world to the high-performance possibilities of the short board”. But as for Evolution, look at the cast: Nat, Ted Spencer and the extraordinary 16-year-old Wayne Lynch. Wayne changed surfing more than any other individual I ever saw. Evolution showed that to the world and was extraordinarily important in that respect.

Surfing in the late 60s and early 70s was connected to counterculture and psychedelic music. Do you think surfers, photographers or artists have to be rebels in order to be successful or get a wider exposure?

Well, everything in the late 1960s and 70s was influenced by the counterculture to some degree… even if it was simply in the rejection of it. In the Australia of my experience, there was a natural fit with surfing. These were the years of Australia’s involvement in the war in Vietnam, and distrust of government wasn’t restricted to the young. It seems to me that many surfers are intuitively anti-authoritarian… scepticism is a useful quality to have in your armoury.

Like you say, Australia got involved in the Vietnam War, but people in other countries do not seem to remember this fact. Were there demonstrations in the streets? Did you attend any of them?

I was at university in Sydney in 1971 when the anti-Vietnam War protests were at their peak. Lectures were rescheduled so that we could attend the marches. Australia had never seen protests on this scale before. We closed down the centres of the major cities… and nothing radicalised me in the way that this issue did. I honestly hadn’t thought that governments would lie to us in the way that they did.

What is the story behind Tracks magazine? I have read that you founded it in 1970 together with Alby Falzon and David Elfick…

I’d been editing a magazine called Surf International and I got sacked. Albe was working for Bob Evans at Surfing World and had a film of his own in mind. David Elfick worked for a pop newspaper and had wider publishing experience that Albe or I did. I needed a job, Albe wanted a vehicle to promote a film, and David had more than enough enthusiasm to manage a couple of projects at one time… the result was the tabloid Tracks. It was radically different to the glossy colour magazines of the time, and the editorial content added social and environmental issues to the primary interest of surfing. We were vulgar and rude and an almost immediate success.

Thanks to your work, you had the chance to travel all over the world. What do you remember about your trip to Portugal in 1976? Did you also visit Spain? I am sure you found great waves…

I spent eight months in Europe in 1976, including a first visit to Portugal. An Australian friend Mark Allon and I had no car, so we walked north from the town of Ericeira trying to find a break that I’d heard about. We found what we thought was Dos Coxos, but there was little swell. It reminds me that surfing adventures aren’t just about finding waves. I was back in Europe in 1979… this time with a little Citroen, and this time hopeful of finding more surf. I left Guethary in SW France without a ripple disturbing the Atlantic Ocean, and it stayed that way right across the top of Spain. I’d seen pictures of Mundaka that enticed me, but it was a beautiful pond when I saw it. In Portugal, at Dos Coxos, finally, there was swell… and those were possibly the finest waves I’d surfed In Europe.

Regarding your trips to Spain and Portugal… what do you remember most about those countries? Met any people there?

In Spain I remember the landscape most of all… the endless hills dotted with olive trees like a giant abstract painting. And being taken by friends to eat tapas in San Sebastián. In Portugal, it was the all-pervading smell of sardines cooking in Ericeira… and the vinho verde of course. I loved the ever-changing local foods and wines of Europe. It was a wonderful place to go surfing.

You took many photos of legendary Australian surfers and many of them became good friends of yours, so I would like to ask you about them. What about Bob McTavish and his influence as a shaper?

It’s undeniable I think that Bob was hugely influential during the development of the shortboard. I wasn’t interested in surfboard design then, and I’m less interested now. Most of my friends never stopped talking about it. Bob’s enthusiasm was infectious… just not on that subject for me.

How was your connection with Nat Young? What was he like in those days?

I took my first surfing photographs with a borrowed camera and lens of Nat at his home break of Collaroy in 1961 when he was 14. We went on many surfing trips over the years, and he’s one of my oldest friends. Nat’s a natural libertarian… he thinks that he should be able to do anything he wants to. He’s always been a risk-taker… that’s never changed.

One of my favourite surf filmmakers is George Greenough. When did you meet him? Did you travel together in those days?

I’m guessing that I first met George in early 1966. I certainly ran a short piece on him in the ‘New Era’ issue of Surfing World that I produced for Bob Evans in July/August of that year. George is a fascinating character, and an inspirational surfer. Bob McTavish has said that the motivation for the shortboard revolution was to build stand-up boards that they could surf in the way George did on his kneeboard. I was working for surfing magazines for a decade from the mid-1960s and saw George fairly regularly. The only time we travelled together was the trip to Hawaii in late 1967. The transparency for this shot got lost, so this is a ‘rescue’ scan from a book. It’s the most radical bottom turn that I’ve ever seen… George Greenough at Honolua Bay in 1967.

One of your favourite photos is not a surfing image, but a photo of a group of surfers hanging out in front of a house. Why do you think surfers’ lifestyle became that iconic? Did you feel that you and your friends were creating a new trend along the way?

Pictures of the world around surfing are the ones that interest me most these days. It was my natural inclination to document the world I was a part of, and I was clearly carrying a camera a lot. The picture that you refer to is called A house at Torquay, and it’s in a small handful of my favourite pictures. Surfing was totally authentic during these years because there was no reason for it to be otherwise. Eventually that changed, and the authenticity was ‘borrowed’ by advertisers to lend credibility to their products. I was working for magazines that played a part in that process, so it’d be hypocritical of me to complain about it now. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s impossible not to think that we were very naïve. I don’t think that you can create iconography… but we were observing and recording what we saw around us. Mostly it seems to take decades to be able to tell when you got it right and when you didn’t.

Recently you have published some photo books with your surfing images. What was the aim behind these projects? Did you discover something that you didn’t remember?

There have been three publications, but only two books, and they’ve been spread over six years. The first was a modest publication that was financed by the gallery I’ve shown with in Sydney. I’ve worked in the design and production of illustrated books for over 20 years, so I could do everything else. In 2013 Rizzoli in New York published a book of my pictures. They did a beautiful job and I’m honoured by it. It’s as close to the definitive collection of my photographs as will ever happen. No ‘discoveries’ in any real sense, but the Rizzoli book was interesting because it was intensely collaborative, and things were done with my pictures that I would never have done myself. That did open my eyes to some extent, and was a great experience.

Nowadays, many people are coming back to a basic way of life in order to be more socially / ecologically responsible. The things you did and learnt in those days, have been useful as you grew older? Do you consider yourself an activist in some way?

That period influenced my life significantly. I’m not in those pictures, but really it’s my life I’m documenting. I was somewhat evangelistic at that time (1969–70), but am now content to just do what I do, live as I live, and if that influences anyone, that’s fine. And if it doesn’t? That’s fine too. I started building my first house at Angourie in November 1972. The basic idea was to drop a building into the natural landscape with the least disruption. Ten years ago I finished the house that I live in now… and the basic design principles were exactly the same.

Are you still connected in some way to the surf industry and its scene?

No, not at all. Most of my friends from those times are still my friends, and some of them are still involved. I watch from the side lines.

What are you up to nowadays? Are you still taking pictures and travelling?

I sell prints from my website – johnwitzig.com.au – and there are continuing enquiries from magazines and books. It seems that interest in the 1960s is inexhaustible. I travelled through Asia for some years as I used to do press checks when the books I was working on were being printed in Singapore. That gave me the luxury of visiting some wonderfully exotic places. I took a lot of pictures on those trips, but my travelling years are mostly over now. That’s okay… I saw some great parts of the world.

www.johnwitzig.com.au