{english below} Stefan Sagmeister tuvo la lucidez de percatarse a tiempo de que, quizá, conviniese buscar distintos enfoques de la realidad y, lo que exige más esfuerzo aún, decidió no conformarse con lo que le contaban los medios sino investigar para forjarse una visión propia y más ajustada a la verdad de los hechos. Lo que nos cuentan condiciona nuestra manera de estar en el mundo, de posicionarnos, nuestra percepción y, por consiguiente, la forma de pensar y actuar.

En el ámbito de la salud alimentaria, hace ya mucho que se popularizó esa máxima según la cual Somos lo que comemos. Pues si la extrapolamos al campo de la información y de las noticias, podría afirmarse que Somos lo que nos cuentan (con todas las implicaciones que acarrea esa frase). Si te pintan un mundo horrible, lo normal es que vivas sumido en un miedo constante y desconfiando del prójimo, encerrándote en ti mismo en lugar de abrirte. Estamos hartos de oír que vivimos la peor época posible y que nos estamos yendo a pique como civilización.

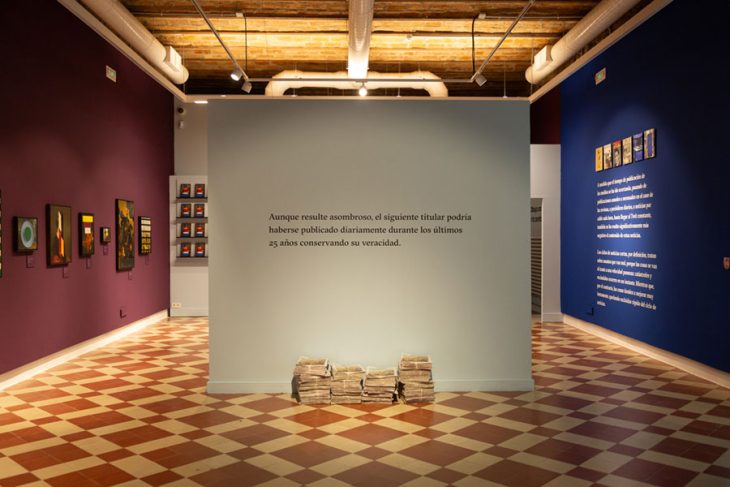

Pues bien, Stefan decidió apoyarse en datos estadísticos irrefutables para desmontar esa falacia. En numerosos aspectos (que tienen que ver con la salud, la educación, el trabajo, etcétera) nunca se ha vivido mejor. Afirmar lo contrario revela una gran desinformación e ignorancia, un sesgo, en gran medida, propiciado por los medios y el interés que suscitan las noticias catastrofistas y morbosas. En la exposición ‘Better’, cuyo comisariado y producción en Europa ha sido llevado a cabo por Juanjo M. Fuentes y que llega a Málaga a La Térmica como un estreno absoluto a nivel de España y practicamente de la mayor parte de Europa, Stefan nos muestra otro ángulo, nos invita a mirar de otra manera, nos cuenta otra historia, y lo hace usando su maestría e ingenio como diseñador combinados con datos estadísticos irrefutables porque, como el mismo nos dice, los números también pueden ser bellos.

Disfruta de esta interesantísima muestra hasta el 2 de marzo en las dos salas principales expositivas del CC La Térmica en Málaga.

A través de datos estadísticos representados en pinturas al óleo intervenidas, carteles, videos y ropa, expones las mejoras logradas en los últimos siglos transmitiendo un mensaje optimista que ofrece una visión a largo plazo. ¿Hubo un momento específico (una especie de punto de inflexión) en el que cambiaste tu forma de ver el mundo? ¿O fue algo más progresivo?

Empecé a reflexionar sobre este tema al ser invitado como diseñador residente en la Academia Americana en Roma. Trabajaba en un estudio precioso y participaba en los fabulosos almuerzos y cenas con artistas, escritores, arquitectos y arqueólogos en el patio. Los compañeros de mesa cambiaban en cada comida, y una noche terminé sentado junto a un abogado muy perspicaz, que trabajaba en la corte europea. Empezamos a hablar de política, y me dijo que lo que ahora estamos experimentando en Hungría, Polonia y Turquía, pero también en Brasil y en los EE.UU., es realmente el fin de la democracia. Así que, después de la cena, ¡me puse a investigar! ¿Cuándo comenzó la democracia moderna? ¿Cómo le ha ido en los últimos dos siglos? ¿Dónde estamos ahora? Pues bien, en 1823, se podría decir que solo existía una democracia, los Estados Unidos. En 1923, ya había 18 países democráticos, después de la Primera Guerra Mundial. En 2023, ahora tenemos 96 países democráticos; por primera vez en la historia humana, más de la mitad de la población mundial vive en una democracia, ¡así que NO PODRÍA HABER ESTADO MÁS EQUIVOCADO! No solo no estamos viendo el fin de la democracia, sino que estamos viviendo en la auténtica edad de oro de la democracia. Esto me resultó interesante: una persona inteligente, muy educada, que claramente no tenía una idea real del mundo en el que vive.

Entiendo que las fuentes de información fueron muy importantes para dar credibilidad al mensaje. ¿Fue esencial en este caso ofrecer cifras para convencer a la gente? “Un número vale más que mil palabras…” ¿Podríamos decir algo así?

Lo veo en dos partes: una es la impresión que obtiene el espectador al ver la exposición en su conjunto, y otra si observa una pintura específica con datos particulares incrustados en ella. Y sí, siento que la precisión y la posibilidad de verificar estos datos son muy importantes.

¿Alguien ha criticado este enfoque positivo o basado en datos optimistas como una forma de ignorar o encubrir los verdaderos problemas?

Algunas personas han interpretado que creo que todo está bien y que todos deberíamos relajarnos. Pero eso está lejísimos de lo que realmente pienso: creo que todas las noticias negativas son necesarias para impulsarnos a actuar. Pero también lo es la información sobre desarrollos positivos. Si queremos lograr CAMBIOS, necesitaremos ambas cosas.

¿Cuál suele ser la reacción del público ante los datos?

Me alegra poder decir que las reacciones a nuestras exposiciones y las charlas han sido muy positivas. Especialmente después de las presentaciones tengo la posibilidad de hablar con la gente, ya sea en la sesión oficial de preguntas y respuestas o después, de forma individual. Las reacciones han sido muy buenas. Recientemente di la charla “Now is Better” en Ucrania. Inicialmente, no estaba seguro de si nuestro mensaje central sobre el pensamiento a largo plazo y “Now is Better” sería algo que pudiera ser apreciado en un país que enfrenta dificultades tan reales y significativas. Mis dudas se disiparon cuando quedó claro que nuestro mensaje positivo llegó al corazón y la mente de la gente en Leópolis; de hecho, fue mucho más bienvenido allí que en países y entre personas que viven en situaciones comparativamente pacíficas y seguras

¿Cuáles crees que son las ventajas del diseño frente a sus limitaciones (si las encuentras) al transmitir un mensaje como el que presentas en Better*?

El diseño de comunicación, definido como un lenguaje que combina texto, imágenes y animaciones, es muy versátil para comunicar cualquier mensaje. Aunque la mayoría de los estudios de diseño en el mundo lo usan para vender o promover algo, funciona particularmente bien para transmitir un mensaje no comercial específico.

Involucras tu propia historia familiar, usándola como ejemplo. ¿Fue una forma de transmitir al espectador una sensación de autenticidad? Como decir ‘expongo mi propia historia privada para contar algo en lo que creo firmemente’.

Muchas personas sienten que los datos y las estadísticas son fríos y difíciles de relacionar. Traigo a mi familia para mostrar que esta situación en el siglo XIX fue real, que la gente realmente vivía así.

¿En qué sentido crees que poner el énfasis en lo positivo también puede ayudar a resolver nuestros problemas actuales?

Si observamos la investigación sobre cómo se lograron los cambios sociales en las últimas décadas, por ejemplo, el cambio en nuestro comportamiento sobre el tabaquismo: muchos países lograron reducir el número de fumadores a la mitad. Esto se logró usando incentivos positivos y negativos: existía la promesa de ahorrar dinero y las fotos impactantes en las cajetillas de cigarrillos. Estos resultados sorprendentes se lograron con la zanahoria y el palo. En este momento, los medios nos entregan mucho del palo. Mi objetivo es ofrecer un pequeño bocado de zanahoria.

¿Qué datos específicos te sorprendieron más? Es decir, ¿dónde has visto una mayor discrepancia entre lo que tendemos a pensar y lo que nos dice el dato objetivo?

El valor energético de una dieta típica en Francia hace 200 años era el mismo que el de Etiopía 200 años después, cuando Etiopía era el país más desnutrido del mundo.

¿Fue difícil escoger qué técnicas utilizar en este trabajo para hacer el mensaje más poderoso?

Tenía todo el sentido del mundo visualizar los datos de 200 años en pinturas, que ya existían hace 200 años cuando comenzamos a recolectar esos datos. Y dado que estas pinturas ya han sobrevivido siglos, es muy probable que sigan en el futuro.

¿Por qué crees que las noticias negativas tienen mayor impacto en los medios? ¿Crees que es posible cambiar esta tendencia?

Hay varios factores: Para empezar, la amígdala, una pequeña masa en el cerebro central en forma de almendra, agrava el problema, transmitiendo los mensajes negativos mucho más rápido que los positivos para mantenernos a salvo. El cerebro de nuestros antepasados prehistóricos requería un atajo para las noticias negativas: era extremadamente importante detectar ese león rápidamente, ya que la alternativa era la muerte. El cerebro nunca desarrolló un atajo similar para los mensajes positivos. Si se perdía el plátano, tal vez habría otro más adelante. Hoy vivimos en condiciones mucho más seguras y nuestras vidas estarían mejor informadas si estuviéramos más receptivos a las noticias positivas. No creo que la gente que dirige los medios sea malintencionada; simplemente aprovechan nuestro interés natural por el drama y los mensajes negativos. La minería de sentimientos es un método de investigación que revisa las noticias en busca de palabras frecuentes como “bueno”, “terrible” y “horrible”, para contar cada uso y su contexto. Esta investigación valida mi intuición, confirmando que el aumento de la negatividad de las noticias en las últimas décadas es científicamente comprobable. Además, a todos simplemente nos resulta el drama más fascinante. Trabajando en ‘The Happy Film’, un documental sobre mi propia felicidad, nuestro equipo hizo un gran esfuerzo enviando a todo el equipo de filmación desde Nueva York a Bregenz para entrevistar a mis hermanos. No participé en esas entrevistas, ya que quería que mis hermanos tuvieran la oportunidad de hablar libremente sobre todas las cosas horribles que debo haber hecho mientras crecía. Cuando revisé las grabaciones semanas después, todos habían hablado solo sobre eventos positivos. Y fue muy aburrido. No usamos ni un solo fotograma.

¿Sientes una responsabilidad ética o moral al tener una amplia audiencia receptiva a tu trabajo? ¿Sientes que debes usar esa visibilidad para construir una sociedad mejor?

En realidad no siento obligación de hacer nada. Si quisiera, también podría tirarme en la playa y leer libros. Pero sucede que prefiero estar involucrado en algo que tiene significado para mí.

¿Crees, por tu experiencia, que hay personas con una tendencia natural hacia una percepción catastrofista de la realidad y otras que, por el contrario, tienden a ver el lado positivo de las cosas?

¡Claro que sí! Algunas personas son claramente más optimistas que otras. Sería interesante ver si existe un estudio que determine cuánto de eso es innato o aprendido, genético o cultural. Lo busqué: aunque hay un componente genético significativo para el optimismo/pesimismo (entre un 25 y 35%), factores ambientales como la crianza, el entorno familiar, el nivel socioeconómico y las experiencias de vida juegan un papel importante en la formación de estos rasgos. La naturaleza y la crianza contribuyen sustancialmente, con los factores ambientales probablemente teniendo una influencia algo mayor en general. El desarrollo del optimismo o pesimismo implica una interacción compleja entre predisposiciones genéticas y experiencias ambientales a lo largo de la vida.

¿Qué artistas, ya sean diseñadores, escritores, cineastas, músicos, políticos o filósofos, etc., te han influido o estuvieron en tu mente durante el proceso de Better?

Hubo varias personas que encuentro inspiradoras: Steward Brand, Danny Hillis y Brian Eno de la Sociedad del Long Now, Steven Pinker en Harvard, Max Roser en Oxford y el historiador Yuval Noah Harari. Y, por supuesto, Hannah Richie, también en Oxford.

Las personas a menudo ven los números y las matemáticas en general como algo aburrido y poco poético. Con el adjetivo ‘Hermoso’ les das otro aspecto a los números. ¿Era ésa tu intención?

Sí. Y por supuesto, en esta exposición, me enfoco principalmente en desarrollos positivos.

“Hace cien años, una de cada 100 mujeres moría en el parto. Hoy, 99 de cada 100 mujeres sobreviven al cáncer de mama. Tener un hijo solía ser tan peligroso como el cáncer hoy”. Del mismo modo, destaca que la edad promedio que una persona solía vivir en 1800 era de 29 años, mientras que en 2020 llegó a los 71 años. ¿Puedes compartirnos otro dato que no usaste en Better pero que pruebe la misma teoría?

Responderé con una pregunta para los lectores: ¿Cómo se correlaciona la huella promedio de CO₂ de nuestros abuelos con la nuestra?

1 – ¿El doble que la persona promedio de hoy?

2 – ¿Aproximadamente la misma que hoy?

3 – ¿Una cuarta parte de la actual?

Has declarado que “El mundo es horrible y fantástico”, y que tu visión depende completamente del marco temporal que elijas para verlo. ¿Podría entrenarse o educarse esta forma más constructiva de ver el mundo?

Sí. Necesitamos que la enseñanza de la historia en las escuelas cambie, de enseñar sobre la vida de los reyes y papas a una historia social que muestre cómo vivía la gente, qué comía, cómo trabajaba, cómo moría.

Has empleado estadísticas de la ONU, el Banco Mundial y otras bases de datos nacionales e internacionales para transformarlas en representaciones visuales cautivadoras y accesibles al público. Cuéntanos algo sobre la metodología, sobre este arduo proceso de investigación. ¿Ha sido un proceso acompañado en todo momento del morbo de lo detectivesco o más bien tedioso a veces?

Afortunadamente, ahora hay muy buenas fuentes disponibles, lo que hace que el trabajo de detective sea bastante sencillo: he estado siguiendo a Steven Pinker en Harvard y Max Roser en Oxford. La mayoría de nuestros datos provienen de ellos u otras fuentes confiables.

Los seres humanos tienden a querer mejorar ad infinitum, sin preocuparse tanto de si estaban mejor o peor antes, sino tomando el momento actual como punto de referencia. ¿Podríamos hablar de un inconformismo humano inherente?

Claro que siempre queremos avanzar y mejorar, la evolución incorporó esto en nosotros. Un conocimiento adecuado de dónde estábamos y de dónde venimos puede resultarnos muy útil para decidir hacia dónde vamos.

Para finalizar, cuéntanos algo sobre tu experiencia en Málaga. Sé que no es tu primera vez. Cuéntanos algo sobre tu relación con esta ciudad y tu experiencia con la exposición en La Térmica.

Sí, he estado en Málaga antes, así que ya conocía la apertura de la gente y el brillo de la luz. Esta vez he centrado casi toda mi visita en la exposición en La Térmica: estaba súper contento con la instalación en sí y la atención al detalle por parte de todo el equipo. Y también tuve ocasión de ver otras exposiciones excelentes, como las de Julian Montague de Moments y la exposición de Joel Meyerowitz en el Museo Picasso.

Respuesta a la pregunta sobre CO₂: La respuesta correcta es A. Este dato sorprendente fue casi increíble para mí: mi abuela nunca tuvo un automóvil, nunca voló en un avión y remendaba todos sus calcetines. ¿Cómo es posible entonces? Esta generación usaba la energía de forma tan ineficiente -principalmente carbón y madera- que la huella de CO₂ per cápita era el doble que hoy.

ENGLISH:

WE ARE WHAT THEY TELL US.

INTERVIEW WITH STEFAN SAGMEISTER.

Stefan Sagmeister had the clarity to realize in time that it might be worth seeking different perspectives on reality. More demanding still, he decided not to settle for the narratives provided by the media, but to investigate and forge his own vision, one more aligned with the truth of the facts. What we are told conditions how we exist in the world, how we position ourselves, our perception, and consequently, our way of thinking and acting.

In the field of nutritional health, the saying “We are what we eat” has long been popular. If we extrapolate this to the realm of information and news, it could be said that “We are what we are told” (with all the implications that phrase carries). If we are presented with a grim view of the world, it is natural to live in constant fear, distrusting others, and closing ourselves off rather than opening up. We are tired of hearing that we are living in the worst possible era and that our civilization is heading toward collapse.

Well, Stefan decided to rely on irrefutable statistical data to dismantle that falsehood. In numerous areas (related to health, education, work, and more), humanity has never lived better. Claiming otherwise reveals significant misinformation and ignorance—a bias largely fueled by the media and the interest generated by catastrophic and morbid news.

In the exhibition ‘Better’, co-curated and produced by Juanjo M. Fuentes (director of the esteemed Staf organization), debuting in Spain and most of Europe (running until March 2 at La Térmica Cultural Center in Málaga), Stefan show us another perspective. He invites us to see things differently, to hear a different story, and he does so by combining his mastery and ingenuity as a designer with irrefutable statistical data. As he himself points out, numbers can also be beautiful.

Through statistical data represented in intervened oil paintings, posters, videos and clothing, you expose the improvements achieved in recent centuries and claim the optimistic message that offers a long-term view. Is there a specific moment (a kind of turning point), when you change the way you look at the world? Or it was something more progressive?

I started to think about this subject when I was invited to be a designer in residence at the American Academy in Rome. I was working out of a gorgeous studio and participated in the fantastic lunches and dinners with artists, writers, architects and archeologists in the courtyard. These were quite salon-like meals with ever-changing pairings of table mates. One evening I wound up next to a very sharp lawyer, who worked at the European court: We got to talk politics and he told me that what we are now experiencing in Hungary, Poland and Turkey, but also in Brazil and the US is really the end of democracy.

So after dinner I looked it up! When did modern democracy start? How did it do over the past two centuries? Where are we now?

Well, in 1823, arguably only a single democracy existed, the United States. In 1923, there were already 18 democratic counties, following the first World War. in 2023 we now have 96 democratic countries, for the first time in human history more than half of the world population lives in a democracy, so he COULD NOT HAVE BEEN MORE WRONG: Not only are we not seeing the end of democracy, we are living in the absolute golden age of democracy. This was interesting to me: A smart, highly educated person who clearly has no clue about the world he lives in.

I understand that the sources of information were very important to give credibility to the message. Was it essential in this case to offer numbers to convince people? ‘A number is worth a thousand words…’ Could we say something like that?

I see this two-folds: There is one impression a viewer gets when looking at the exhibition as a whole, and then another if she checks out a specific painting with particular data embedded into it.

And yes, I feel that the accuracy and the possibility to double-check this data is very important.

Has anyone criticized this positive or optimistic data-driven approach as a way of turning away from or masking problems?

Some people have interpreted it that I believe that everything is fine and we should all relax. This could not be further from my actual thinking: I do believe that all the negative news are necessary to kick us into action. But so is information about positive developments. If we want to achieve CHANGE, we will need both.

What is the public reaction to data usually?

I can say that reactions to our exhibitions and my talks have been very positive. Specially after presentations I have the possibility to talk to people, be it in the official Q&A session or afterwards individually. There the reactions have been great. I have given the ‘Now is Better’ talk recently in the Ukraine. Initially, I was unsure if our core message about long-term thinking and “Now is Better” would be something that can be appreciated in a country facing such real and significant hardship.

My anxiety evaporated when it became clear that our positive message landed in the hearts and minds of the people in Lviv, – it was actually welcomed much more then among countries and people who live in comparably peaceful and secure situations.

What do you think are the advantages of design versus the limitations (if you appreciate them) when transmitting a message like the one you present in Better?

Communication design, defined as a language that combines text, images and animations, is very well versed in communicating any message. While most design studios around the world use it to sell or promote something, it works specifically well to make a specific non-commercial point.

You involve your own familiar history, using it as an example. Was it a way to convey to the viewer a feeling of authenticity? Like to say, I expose my own private story to tell something I firmly believe in.

Many people feel data and statistics are cold and difficult to relate to. I bring my family in to show that this situation in the 19th century was real, that people really lived that way.

In what sense do you think that putting emphasis on the good can also help to solve our present problems?

If I look at research on how social change was achieved in the past couple of decades, say the incredibly effective change in our behavior about smoking: Many countries could cut the number of smokers in half.

This was accomplished by using positive and negative and incentives: There was the promise of saved money, and the shocking photos on the cigarette packs. The incredible results were created by the carrot and the stick. Right now the media is delivering plenty of the stick. My goal is to offer a small bite of the carrot.

What specific data surprised you the most? That is, where have you seen a greater mismatch between what we tend to think and what objective data tells us?

The energy value of a typical diet in France 200 years agao was the same as the one in Ethopia 200 years later, when Ethopia was the most malnourished country in the world.

Was it difficult to decide which techniques to use in this work to make the message more powerful?

It made a whole lot of sense to visualize 200-years-spanning data on paintings, that have already been around 200 years ago, when we started to collect that data. And as these paintings already survived centuries, chances that they will also be around in the future are very good.

What do you think makes negative news have a greater impact in the media? Do you think it is feasible to turn this trend around?

There are a number of factors: For one, the amygdala — a small, almond-shaped mass in the central brain — compounds the problem, transporting negative messages much faster than positive ones in order to keep us safe. The brains of our prehistoric ancestors required a shortcut for negative news—it was extremely important to detect that lion quickly, as the alternative was death. The brain never developed a similar timesaver for positive messages. If the banana was missed, there might be another one around the corner. Today, we’re all living much safer lives, and our lives would be better informed if we were more receptive to positive news.

I don’t believe the people running our media outlets to be evil; they simply leverage our naturally heightened interest in drama and negative messaging. Most attempts to create a positive news site have failed immediately. Sentiment mining is a research method in which you review the news for frequently used words like “good,” “terrible,” and “horrific,” tallying each use and its context. This research validates my gut feeling, confirming that the increasing negativity of the news over the past few decades is scientifically provable.

And also, we all simply find drama more fascinating. While working on The Happy Film, a documentary about my own happiness, our team went through the considerable trouble of sending the entire film team from New York to Bregenz to interview my siblings. I purposefully did not take part in these interviews, as I wanted my brothers and sisters to have a chance to speak freely about all of the awful things I must have done growing up. When I checked the footage weeks later, they had all talked only about positive events. This was incredibly boring. We wound up using not a single frame.

Do you feel an ethical or moral responsibility having a wide audience receptive to your work? Do you feel that you have to use that visibility to build a better society?

I actually don’t feel an obligation to do anything. If I would like it, I could also lay on the beach and read books. But it so happens that I much rather would be involved in something that carries meaning for me.

Do you believe from your experience that there are people with a natural tendency towards a catastrophic perception of reality and others who, on the contrary, tend to see the good side of things?

Yes, of course! Some people are clearly more optimistic than others. It would be interesting to see if there is a study out there that determines how much of that is nature or nurture, genetic or cultural.

I just looked it up: While there is a significant genetic component to optimism/pessimism (around 25-35%), environmental factors like parenting, family environment, socioeconomic status, and life experiences play a major role in shaping these traits. Both nature and nurture contribute substantially, with environmental factors likely having a somewhat larger influence overall. The development of optimism or pessimism involves a complex interaction between genetic predispositions and environmental experiences throughout life.

Which artists, be they designers, writers, filmmakers, musicians, politicians or philosophers, etc., have influenced you or were in your mind during the process of Better?

There were a number of people I find inspiring: Steward Brand, Danny Hillis and Brian Eno from the Society of the Long Now, Steven Pinker at Harvard, Max Roser at Oxford and the historian Yuval Noah Harari. And of course, Hannah Richie, also at Oxford.

People often see numbers and mathematics in general as something boring and unpoetic. With the adjective ‘Beautiful’ you give to the numbers another aspect. Was that the intention of the title?

Yes. And of course they in this exhibit, I mostly look at positive developments.

“One hundred years ago, one in every 100 women died in childbirth. Today, 99 out of every 100 women survive breast cancer. Having a child used to be as dangerous as cancer today.” Likewise, it highlights that the average age that a person used to live in 1800 was 29 years, while in 2020 it reached 71 years. Can you share with us another data that you didn’t use in Better but prove the same theory?

I’ll answer with a question for your readers: How does the average CO2 footprint of our grandparents compare to ours?

1 – Twice the size of the average person today?

2 – About the same as today?

3 – A quarter of the size as it is today?

You have stated that The World is Horrible and Fantastic, both statements are true and my view depends entirely on the time frame I choose to watch it. Could this more constructive way of seeing the world be trained or educated?

Yes. We need the teaching of history in the schools change from teaching the lives of the kings and popes to a social history, and shows how people lived, what they ate, how they worked, how they died.

You have used statistics from the UN, the World Bank and other national and international databases to transform them into captivating visual representations accessible to the public. Tell us something about the methodology, about this arduous research process. Has there been something detective about it or has it even been tedious at times?

Luckily, there are now very good sources available, that keeps the detective work rather simple: I have been following Steven Pinker at Harvard and Max Roser at Oxford. Most of our data comes from them or other reliable sources.

Human beings tend to want to improve ad infinitum, not caring so much about whether they were better or worse before, but rather taking the current moment and situations as a reference point to want to move forward. I remember Maslow’s famous pyramid, for example. Can you connect this idea in some way with ‘the idea’ behind Better? Do you think could we talk about an inherent human nonconformity?

Of course we always want to move forward and better ourselves, evolution built this into us. A proper knowledge of where we were and where we come from is extremely helpful in deciding where we are going.

To finish, tell us something about your experience in Malaga. I know is not your first time. Tell us something about your relationship with this city and your experience with the expo in La Térmica.

Yes, I’ve been to Malaga before so I already knew about the openness of the people and the brightness of the light. This time my time my time circled around the exhibit at La Termica: I was super happy with the installation itself and the attention to detail paid by the whole team. And I also had a chance to see some excellnet other shows, notably the ones by Juilan Montague in Moments as well as the Joel Meyerowitz exhibit at the Museo Picasso.

Answer to the CO2 question: Correct is A. This surprising data point was almost unbelievable to me: My grandmother never owned a car, never flew in a plane and mended all her socks. How is this possible? This generation used energuy so inefficiently, – mostly coal and wood – that the per person footprint was double as it is today.