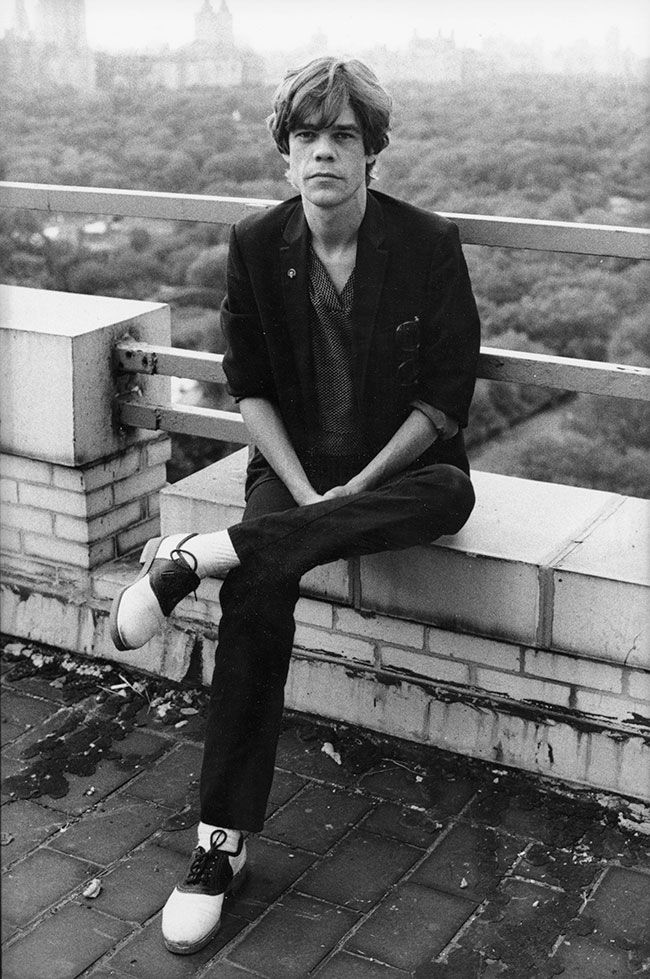

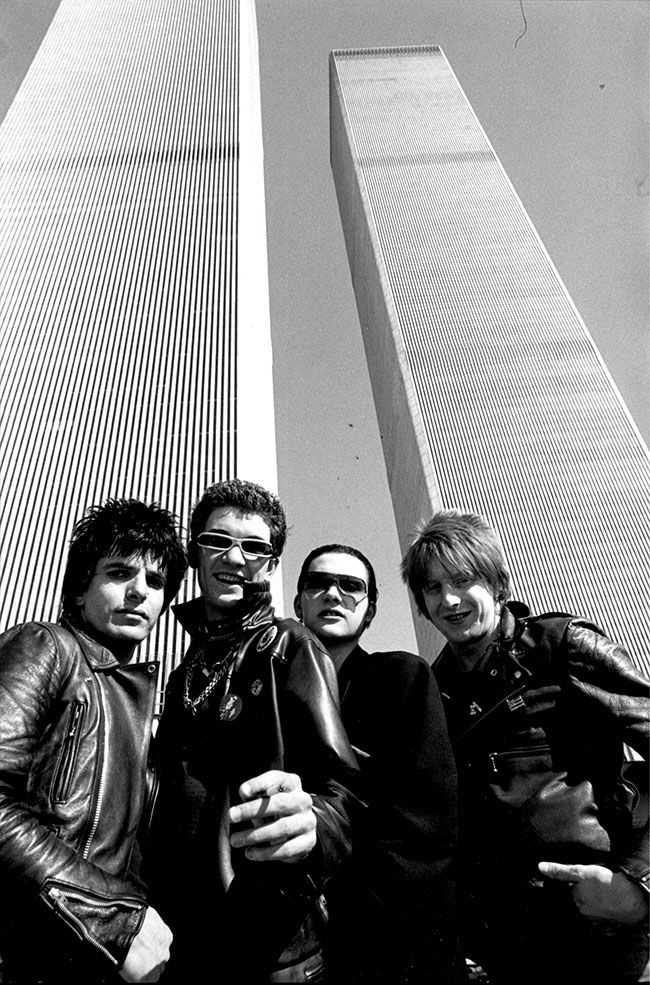

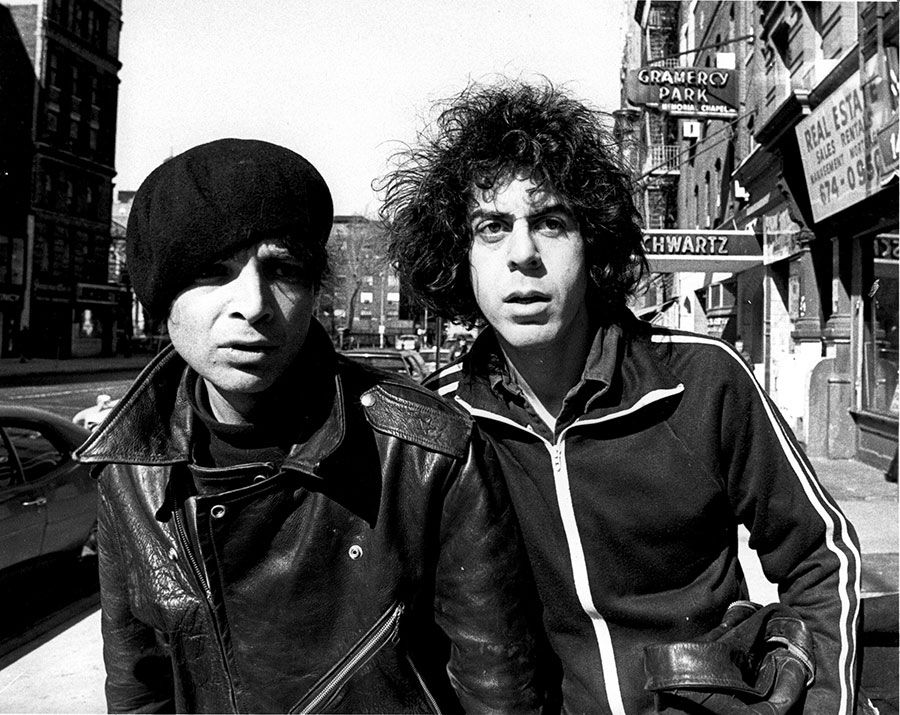

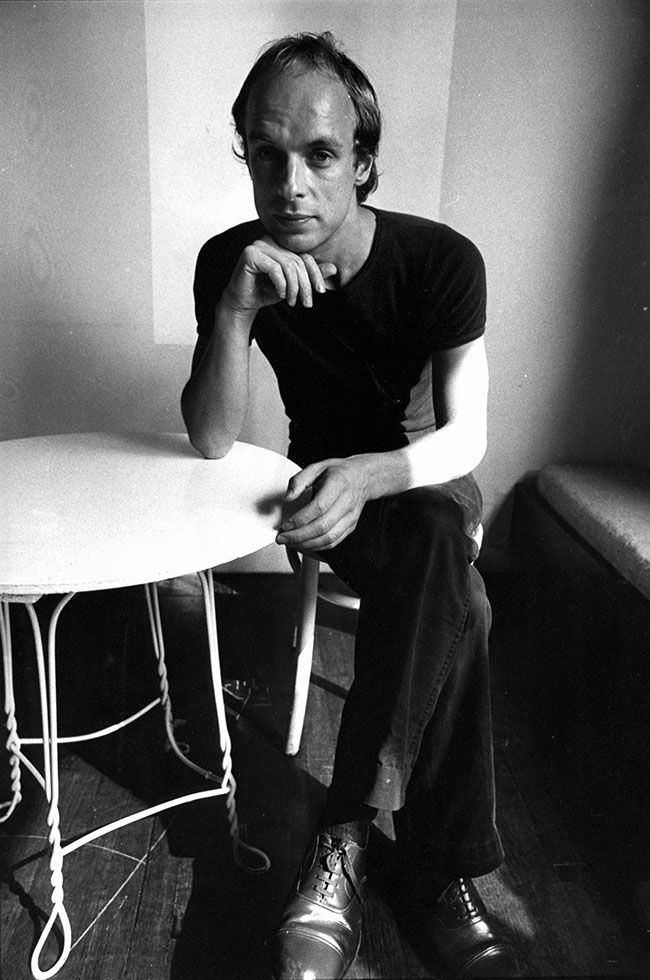

{english below} Bayley ha construido una forma de ver, constituida por una manera muy natural de acercarse a la música. Una naturalidad que viene de la cercanía, de hacer fotos a sus amigos. Fotógrafa de la revista Punk, ha tejido todos los mimbres de la representación fotográfica de la música undergound. Pensemos en la portada del primer LP de Ramones o los The Dammed con las torres de gemelas de fondo o Debbie Harry con Joey Ramone. Todas han pasado a nuestro imaginario y, rápidamente, las identificamos con una época en la que parecía que se podían cambiar las cosas.

El punk es de los pocos géneros musicales históricos que siguen vivos y en permanente mutación ¿En qué piensas que consiste su vitalidad?

El punk nunca fue sólo un género. Especialmente al principio (1974 -1976) todas las bandas principales de Nueva York eran muy diferentes: The Ramones, Blondie, The Heartbreakers, los Voidoids, Talking Heads. Había bandas de blues en el CBGB, bandas de rock artístico, bandas de pop, de todos los géneros. El punk tenía un gran paraguas que acomodaba muchos estilos, pero más tarde la definición se hizo más específica y estrecha: rápido, fuerte, agresivo. A medida que el punk se convirtió en hardcore, hubo todo tipo de subconjuntos de música. Lo principal era la actitud – una cierta irreverencia hacia lo tradicional, una sensación de que todo estaba bien.

Muchas de tus fotografías se han convertido en un referente visual, pero, ¿crees que en su momento tu trabajo no fue comprendido?

Creo que mi trabajo es bastante sencillo, ¡no creo que haya nada que “entender”! Es difícil recordar que las peculiaridades del punk se consideraban “chocantes” y eran ofensivas para la gente. Mi estilo es el documental. Mis fotos favoritas son las sinceras, las que muestran la vida como un acontecimiento. Algunas de mis fotos se hicieron icónicas porque el punk también lo hizo. Me complace y me sorprende que la gente siga teniendo tanta curiosidad por los años 70. Estábamos viviendo nuestras vidas. Yo también viví los 60, donde había una verdadera sensación de que todo estaba cambiando a mejor, la paz y el amor. Eso no funcionó. El punk era más sobre las realidades de la vida – pero con el pelo corto! Había más ira, supongo, aunque no recuerdo haber estado enfadada ¡Me estaba divirtiendo demasiado!

Pienso en la famosa fotografía que fue portada del primer LP de Ramones y en su aparente sencillez que hace tener la complicidad con los músicos, algo que es frecuente en el punk. Cuéntanos la intrahistoria de esta fotografía.

¡Debo haber contado esta historia un millón de veces! La compañía discográfica de Ramones (Sire) había contratado a un fotógrafo “profesional” para hacer la sesión de portada, pero a nadie le gustaron las fotos. La revista Punk estaba a punto de poner a Ramones en nuestro tercer número, así que habíamos hecho una sesión de fotos con ellos por esa época. Danny Fields, el manager de Ramones, llamaba a los fotógrafos para ver si tenían fotos recientes, y yo le envié a Sire mis hojas de contactos, y el resto es historia. Me pagaron 125 dólares. Como he dicho muchas veces, el hecho de que conocía a los miembros de la banda, y que nunca fue una portada de un disco, probablemente me quitó presión a mí y al grupo. Fue una sesión de fotos casual, probablemente duró menos de una hora, ¡tuve suerte!

En cierta ocasión comentaste que la actitud DIY fue importante a la hora de hacer fotografías, ¿había un rechazo a la técnica buscando algo más espontáneo?

No hubo ningún “rechazo a la técnica”… ¡En realidad no tenía ninguna técnica! Aprendí a revelar mis propio carretes y a imprimir mis propias fotos, pero más allá de eso, sólo era pulsar el obturador. ¡Nunca usé un medidor de luz porque no sabía cómo! Para mí, la fotografía se trata de ver, y supongo que sabía cómo ver.

¿Cuáles eran tus fotógrafos favoritos en aquella época?

Conocía a los fotógrafos contemporáneos que empezaban a ser reconocidos, como Diane Arbus y Roberta Frank, pero no conocía su trabajo en profundidad. Me encantaba la fotografía de moda, y los años 50, 60 y 70 fueron una época dorada: Avedon, David Bailey, William Klein, Jerry Schatzberg… Son demasiados para nombrarlos. Crearon un mundo de fantasía, belleza, glamour y sexo, me quedé muy impresionada con todo eso. Luego, muchos de esos mismos fotógrafos, comenzaron a fotografiar bandas de rock a medida que el género crecía. Es bastante gracioso que el punk fuera considerado “anti-moda” y, sin embargo, la influencia del punk está siempre presente en la moda, sigue volviendo cada pocos años.

Fuera de la fotografía, ¿qué ideas te movían y cómo piensas que se reflejan en tu trabajo?

Me encanta el cine, siempre fui una gran cinéfila, así que estoy segura de que esto me influenció visualmente. Estaba loca por Frank Sinatra y lo vi actuar en 1976. También soy una gran lectora, así que algunas ideas, probablemente, se colaran también por ahí. Fui a muchos museos y galerías. Todo es inconsciente, todo lo que tomas te afecta. Trato de prestar atención, eso es lo principal. La vida está sucediendo a tu alrededor, todo el rato, ¡así que no te olvides de prestar atención!

Muchas de las grandes instituciones culturales se han interesado por el punk en los últimos años, organizando exposiciones, publicando libros… ¿Piensas que es una forma de desactivar el mensaje del punk?

Hmmm… ¡No estoy segura de que puedas desactivar el punk! Hace unos 35 años, en el Museo Whitney hubo una gran exposición sobre los Beats. Estoy segura de que los mismísimos Beats (Ginsburg, Kerouac, Gysisn, Corso, etc.) nunca imaginaron que eso sucedería porque, como el punk, aquello era un movimiento muy antisistema. Pero al igual que los punks, los Beats en general estaban orientados artísticamente, y dejaron atrás un registro literario y fotográfico. El punk sólo añadió música.

Mc Laren es un personaje que para mí es un enigma, por un lado se le presenta como una especie de artista de vanguardia en la línea del situacionismo, Dadá, etc… y por el otro como un manager sin escrúpulos ¿existe un término medio?

Malcolm McLaren era una persona complicada. Lo conocí en 1973 cuando trabajé brevemente en Let It Rock, que luego se convirtió en Seditionaries. Tenía muchas, muchas ideas todo el rato, una mente muy agitada. El escritor británico Paul Gorman tiene una biografía de Malcolm que sale en abril y que se espera que reúna todos estos aspectos de Malcolm. Pensé que era bastante inescrupuloso con respecto a los Sex Pistols, y también más tarde cuando intentó reclamar la propiedad del negocio de moda de Vivienne Westwood después de que él ya no estuviera involucrado.

¿Cuál piensas que fue su rol en la difusión del punk (exceptuando a Sex Pistols, claro)?

Pasó a otras formas de música como Bow Wow Wow, y luego el hip hop, y luego sus cosas de ópera. El punk se había acabado en 1978, y todo el asunto no tuvo mucha fuerza hasta los 90 con Nirvana y Pearl Jam. El movimiento punk original fue breve, y la gente siguió adelante. Los Ramones son más grandes ahora de lo que fueron en su vida. Pero inspiraron a muchos.

Los 70 fueron un momento en el que el capitalismo empezó a imperar en buena parte del mundo con la consiguiente transformación de buena parte del planeta en lo que a consumidores respecta, creando así nuevas y subjetividades formas alienantes de relacionarnos, ¿fue quizás el punk uno de los últimos intentos de resistencia?

En Nueva York, en los años 70 el capitalismo, básicamente ,había fracasado. En nuestro grupo, pocos teníamos dinero, pero vivir era barato, los alquileres eran bajos y podías vestirte de manera genial por casi nada. No creo que el punk americano tratase de ser anticonsumista: todas las bandas querían ser tan exitosas como fuera posible.

Esa aparición de nuevas subjetividades en un mundo en permanente crisis también es una oportunidad de cambios ¿En qué te cambió el punk?

No creo que el punk me haya cambiado, más de lo que lo hizo el Verano del Amor. Creo que los Beatles fueron el principal catalizador de mi vida, toda la invasión británica. Representó una nueva forma de ser para mí cuando era adolescente. Eran jóvenes, eran geniales, eran alegres y dominaron la cultura brevemente, de manera positiva. Así que creo que los Beatles, precedidos por Elvis Presley, es lo que realmente abrió la puerta a un tipo de cultura juvenil diferente a la que existía antes. No tenías que seguir las reglas. Podías ser “diferente”, no tenías que conformarte. El punk tenía las mismas ideas de rebelión y de ir más allá.

Actualmente, ¿qué discursos fotográficos te interesan?

Aún me encanta la fotografía, imágenes de todo tipo.

www.robertabayley.com

English:

ROBERTA BAYLEY. PHOTOGRAPHER OF THE FIRST PUNK

Bayley has built a way of seeing, constituted by a very natural way of approaching music. A naturalness that comes from being close, from taking pictures of her friends. Photographer of the magazine Punk, she has woven all the strands of the photographic representation of the music undergound. Think about the cover of the first Ramones LP or The Dammed with the twin towers in the background or Debbie Harry with Joey Ramone. They have all passed into our imaginary and we quickly identify them with an era, when it seemed that things could be changed.

Punk is one of the few historical music genres that is still alive and in permanent mutation. What do you think its vitality consists of?

Punk was never just one thing. Especially in the beginning (1974 -1976) all of the main New York bands were very different: The Ramones, Blondie, The Heartbreakers, the Voidoids, Talking Heads. There were blues bands at CBGBs, art rock bands, pop bands, just every genre. Punk had a big umbrella that accomodated many styles, but later the definition got more specific and narrow: fast, loud, aggressive. As punk turned into hardcore, there were all kinds of subsets of music. The main thing was about the attitude a certain irreverence toward the traditional, a sense that anything was okay.

Many of your photographs have become a visual reference, but do you think your work was not understood at the time?

I think my work is pretty straightforward, I don’t think there is anything to “understand”! It’s hard to remember that aspects of punk were considered “shocking” and were offensive to people. My style is documentary. My favorite photos are candid ones, that just show life as its happening. Some of my photos became iconic because punk became iconic. I’m pleased and amazed that people are still so curious about the 70s. We were just living our lives. I also lived through the 60s, where there was a real sense that everything was changing – for the better – peace and love. That didn’t quite work out. Punk was more about the realities of life – but with short hair! There was more anger I guess, though I don’t remember being angry. I was enjoying myself too much!

I think about the famous photograph that was the cover of Ramones’ first LP and its apparent simplicity that makes you feel complicity with the musicians, something that is frequent in punk. Tell us about the intrahistory of this photograph.

I must’ve told this story a million times! The Ramones record company (Sire) had hired a “professional” photographer to do the cover session, but no one liked the pictures. Punk magazine was just about to put the Ramones on our third issue, so we’d done a photo session with them around that time. Danny Fields, the Ramones manager, was calling photographers to see if they had any recent pictures, and I sent Sire my contact sheets, and the rest is history. I was paid $125. AS I have said many times, the fact that I knew the band members, and that it was never meant to be a record cover probably took any pressure off me and the Ramones. It was a casual photo session, probably lasting less than an hour. I got lucky!

You once commented that the DIY attitude was important when taking photographs. Was there a rejection of technique, looking for something more spontaneous?

There was no “rejection of technique”- I actually had no technique! I did learn how to develop my own film and print my own photos, but beyond that, I just pushed the shutter. I never used a light meter because I didn’t know how! To me photgraphy is about seeing, and I guess I knew how to see.

Who were your favorite photographers at that time?

I was aware of contemporary photographers who were beginning to be recognized, like Diane Arbus and Roberta Frank, but I didn’t know their work in depth. I loved fashion photography, and the 50s, 60s and 70s was a golden era – Avedon, David Bailey, William Klein, Jerry Schatzberg, there are really too many to name. They created a fantasy world of beauty, glamour and sex, I was very taken with all that. Then many of those same photographers began to shoot rock bands, as rock got bigger. It’s quite funny that punk was considered “anti-fashion” and yet the punk influence is ever present in fashion, it keeps coming back every few years.

Outside of photography, what ideas moved you and how do you think they are reflected in your work?I love the movies, I was always a big filmgoer, so I’m sure film visually influenced me. I was crazy about Frank Sinatra and saw him perform in 1976. I’m also a big reader, so ideas probably snuck in that way. I went to lots of museums and galleries. It’s all unconscious, everything you take in affects you. I try to pay attention, that’s the main thing. Life is happening all around you, all the time, so don’t forget to pay attention!

Many of the great cultural institutions have taken an interest in punk in recent years, organizing exhibitions, publishing books… Do you think it’s a way of deactivating the message of punk?

Hmmm…I’m not sure you can deactivate punk! About 35 years ago, the Whitney Museum had a big exhibition on The Beats. I’m sure the Beats themselves (Ginsburg, Kerouac, Gysisn, Corso, etc.) never imagined that would happen, because like punk that was a very anti-establishment movement. But like the punks, the Beats in general were artistically oriented, and left behind a literary and photographic record. Punk just added music.

McLaren is a character that for me is an enigma; on the one hand he is presented as a kind of avant-garde artist in the line of situationism, Dada, etc…and on the other as an unscrupulous manager. Is there a middle ground?

Malcolm McLaren was a complicated person. I met him in 1973 when I briefly worked at Let It Rock, which later became Seditionaries. He had lots and lots of ideas all the time, a really churning mind. The British writer Paul Gorman has a biography of Malcolm coming out in April that one hopes will bring all these aspects of Malcolm together. I thought he was rather unscrupulous in regards to the Sex Pistols, and also later when he tried to claim ownership of Vivienne Westwood’s fashion business after he was no longer involved.

What do you think was his role in the diffusion of punk (except for the Sex Pistols, of course)?

He moved on to to other music forms like Bow Wow Wow, and then hip hop, and then his opera stuff. Punk was really over by 1978, the whole thing didn’t really get traction until the 90s with Nirvana and Pearl Jam. The originl punk movement was brief, and people moved on. The Ramones are bigger now than they were in their lifetime. But they inspired so many

The 70s were a time when capitalism began to be triumphant in a good part of the world, with the consequent transformation of a good part of the planet into consumers. Creating new subjectivities and alienating forms of relationship, was punk perhaps one of the last attempts at resistance?

In New York in the 70s, capitalism had basically failed! In our crowd, few of us had any money, but living was cheap, rents were low and you could dress in a cool way for pretty much nothing. I don’t think American punk wasn’t about being anti-consumer – all the bands wanted to be as successful as possible.

This emergence of new subjectivities, in a world in permanent crisis, is also an opportunity for change. How did punk change you?

I don’t think punk changed me, anymore than the Summer of Love did. I think the Beatles were the main catalyst in my life, the whole British Invasion. It represented a whole new way of being to me as a teenager. They were young, they were cool, they were joyous and they dominated the culture briefly, in a positive way. So I think the Beatles, preceded by Elvis Presley, is what really opened the door for a different kind of youth culture than existed before. You didn’t have to follow the rules. You could be “different”, you didn’t have to conform. Punk had the same ideas of rebellion and pushing the envelope.

What photographic discourses interest you today?

I still love photography, images of all kinds.