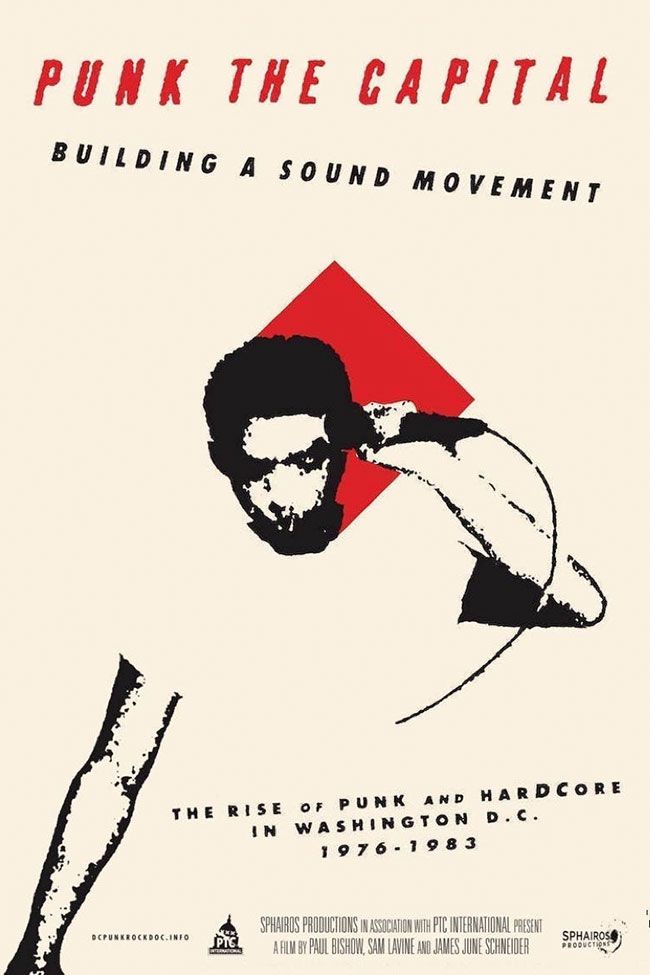

{english below} Documentar requiere de ordenar y preservar, quizás, lo más valioso. Y hablando de un fenómeno tan opaco como es el punk , este trabajo es todavía más importante. No olvidemos que la mayoría de las expresiones del punk suelen pasar desapercibidas y, muchas veces, trazar una clara genealogía del proceso es complicado. Así nos encontramos frecuentemente con historias despojadas de muchas de sus partes, mutilaciones que nos privan de un conocimiento pleno. Por eso es importante este documental , genuino trabajo de arqueología , que nos presenta el punk como una energía polifónica y vital.

Es muy interesante el proyecto de I am eye, un cine fórum de inspiración punk ¿Fue esto en cierta medida el germen de este documental?

James June Schneider: Dejaré que Paul responda a eso ya que él estuvo detrás de la serie de películas I am Eye.

Paul Bishow: I Am Eye se caracteriza por su estética y flujo de trabajo DIY. Queríamos generar un espacio para proyectar y ver películas sin el juicio de comisarios o críticos y sin ánimo de lucro. Si una persona traía una película, la proyectábamos. Muchos cineastas se reunían y discutían entre ellos. A lo largo de los años proyecté muchas de mis propias películas, películas de tipo diario/ensayo con destellos de ficción, pero no eran exactamente ficción. Madams Organ, a la que dediqué una buena cantidad de tiempo, fue, por supuesto, proyectada a menudo.

Durante 9 años estuvo a pleno rendimiento. ¿Cómo fue su funcionamiento?

James: Empezamos a recopilar material alrededor del cambio de siglo e íbamos disparando cuando podíamos, pero sólo cuando me mudé de vuelta a Francia en 2013, realmente empezamos a trabajar en la película con intensidad; eso incluía la campaña de Kickstarter. Nuestro objetivo con este proyecto no era sólo hacer la película, sino también conservar archivos y, de alguna manera, documentar las contribuciones de la gente en la escena musical, así que filmamos muchas más entrevistas de las que necesitábamos para la película, alrededor de 100, cada una de ellas con una duración aproximada de entre 2 y 4 horas. Cosas así no formaban parte de la producción de la película en sí y terminaban, inevitablemente, alargando el proceso. Para este tipo de película tiene muchas ventajas el dedicarles más tiempo. En general, diría que deberíamos hacer menos películas y que éstas fueran mejores. Puedo afirmar que nos tomamos el tiempo que pensamos que necesitábamos. La gran mayoría de películas han sido concebidas bajo una percepción capitalista del tiempo.

¿Crecisteis con la escena de Washington DC?

James: Había, principalmente, tres personas trabajando en la película: Paul Bishow, Sam Lavine y yo. Sam y yo crecimos en DC y ambos hemos tocado en varias bandas. Mi visión del mundo ha sido moldeada por la escena de este panorama. Paul se mudó a DC en 1979 y cayó justo en la zona cero de la escena punk de allí, ¡así que la vio crecer!

Paul: Tenía 27 años cuando llegué a DC.

I’m a eye tiene una fuerte impronta política ¿Cómo fue vuestro proceso de toma de conciencia idiológica?

Paul: Yo era miembro de la Liga de los Trabajadores, un partido trotskista de la 4ª Internacional o algo así. Solía vender un periódico en mítines y protestas (The Bulletin).

El documental aborda los inicios del punk y del HC en Washington del 76 al 83 ¿Por qué esos años en concreto?

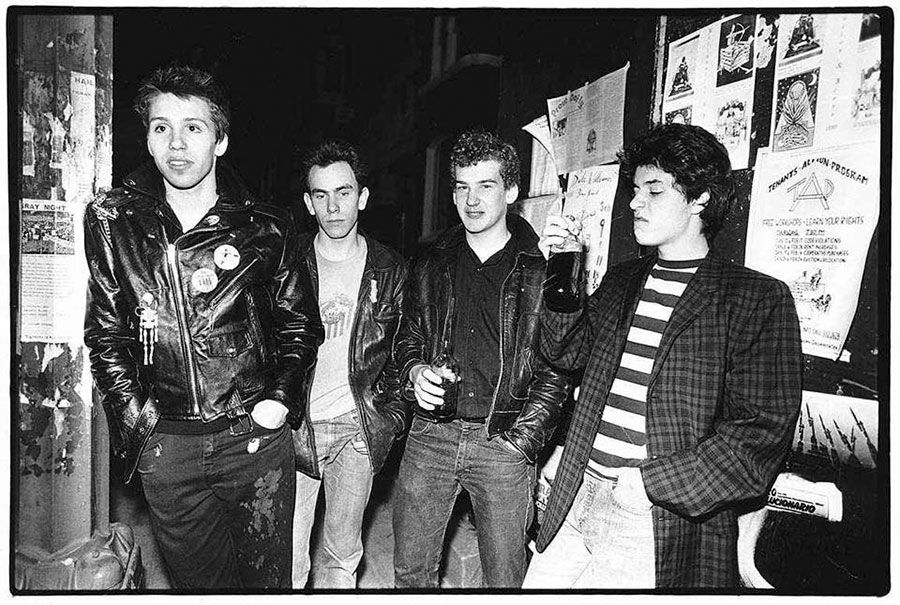

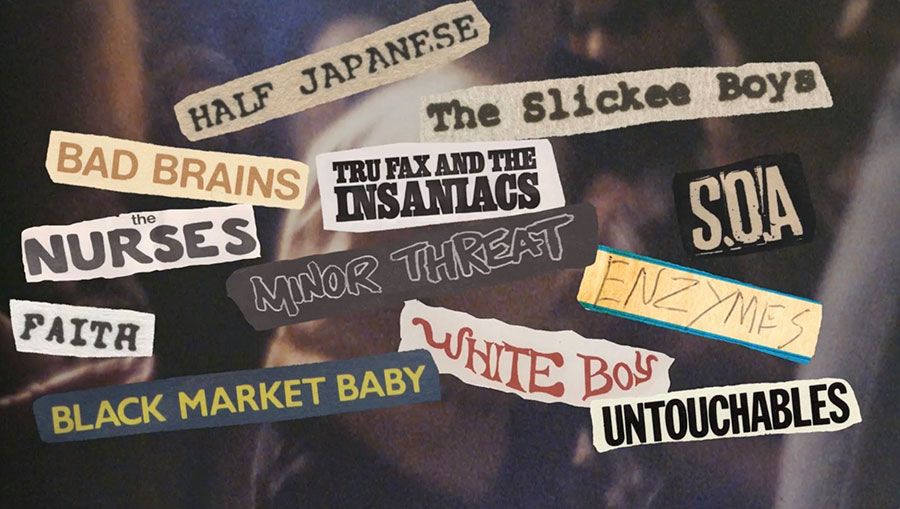

James: Estoy intrigado por cómo arraigan los movimientos, cómo se forman las comunidades en cualquier momento en el que se estén impulsado. La escena punk de DC comenzó alrededor de 1975-1976 al mismo tiempo que en otros lugares y fue, básicamente, un crecimiento constante y rápido hasta alrededor de 1983, cuando HarDCore implosionó aquí. Así que seguimos a algunos de los grupos principales hasta aquel momento: Slickee Boys, Bad Brains y Minor Threat, mientras que, al mismo tiempo, tocábamos a un montón de otros grupos a lo largo del camino. No queríamos hacer una película banda por banda. Más bien la película cuenta una historia y ésta llega a un buen punto y final en 1983/1984.

¿Qué es lo que tenía de especial Washington DC para que surgiese de ella una escena tan dinámica?

James: DC todavía tiene una especie de telón de fondo de potencial, han prosperado movimientos underground pero no ha habido una historia cultural dominante o imponente. Hay muchas casualidades en estas historias, pero en el caso de DC también fue una confluencia de peculiaridades. Para empezar, hubo un grupo de personas increíblemente claras de mente a mediados de los 70 que construyeron una base sólida y querían ver algo suceder, gente como Kim Kane (Slickee Boys), Skip Groff (Yesterday and Today Records) y Howard Wuelfing (The Nurses y varios fanzines); hubo grandes bandas que surgieron alrededor de 1977-1979 y luego llegaron los Bad Brains y pusieron el listón muy alto. Por encima de todo esto, por supuesto, estuvo la fundación de Dischord Records, que incorporó la ética y el enfoque DIY que ya estaban algo presentes en el tejido del panorama; eso le dio patas a la escena y ,el resto, ¡es historia!

Paul: No fue algo exclusivo de DC, creo que todo el mundo del rock estaba preparado. Desde sus inicios, el rock tenía una sensibilidad muy fuerte. A finales de los setenta, el elemento corporativo se había convertido en demasiado para muchos, era el momento de empezar de nuevo en todas partes.

Muchas de las grandes instituciones culturales se están interesando por el punk y su historia, sobre todo por lo que tiene que ver con el legado estético ¿Hasta qué punto crees que hemos asimilado el punk?, ¿se ha convertido en una pieza de museo?

James: El punk de DC se ha convertido en un objeto de estudio y, tal vez, parte de la música es ahora canónica, pero está lejos de estar muerta. Todavía hay muchas nuevas bandas nuevas, ideas y material punk no musical que sale de la gran escena de DC. Ya no es algo que se quede en DC tampoco, está infundido en la cultura popular, la alta cultura, la política (piensa en el candidato presidencial Beto O’Rourke), lo que sea.

Paul: Solía pensar que una vez que algo llega a un museo, su historia se acababa, pero después de 16 años trabajando con los museos del Smithsonian, lo veo distinto. Me gusta la dinámica de la historia como algo vivo (orgánico).

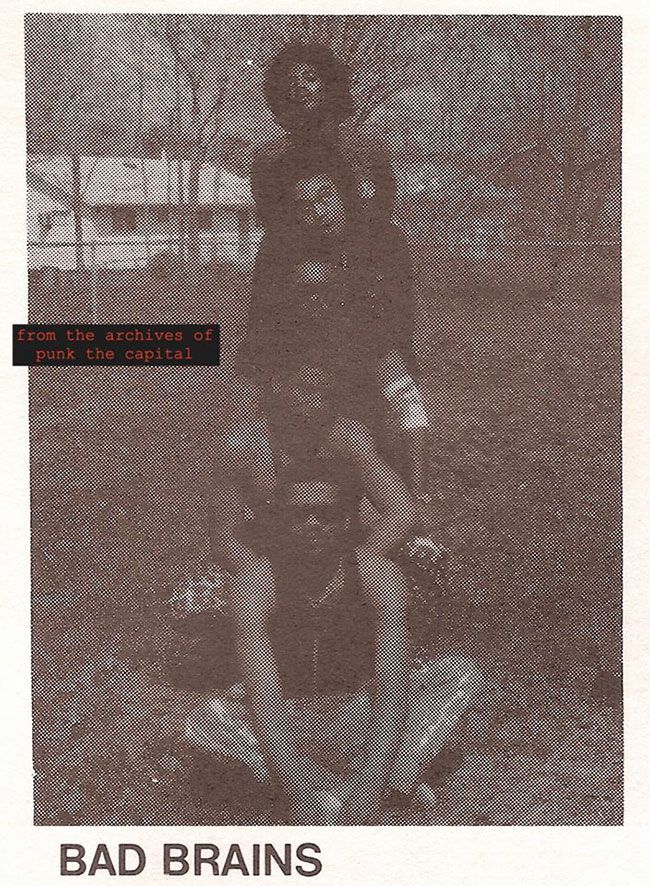

Bad Brains fue un grupo capital en la génesis del HC ¿Crees que han tenido el reconocimiento que merecen?

Paul: La primera vez que vi a Bad Brains no teníamos el término “hardcore”. Eran, claramente, la mejor banda. A día de hoy sigo escuchando que se refieren a ellos como “La mejor banda de hardcore de la historia”, así que, ¡la respuesta es sí!

Es necesario tener un espacio físico para que crezca una escena ¿Qué papel tuvo el Madam´s Organ en esta?

Paul: ¡Realmente ayudaron!

James: Para los Bad Brains y los chicos que empezarían Minor Threat unos meses después de que Madams Organ cerrara, Scream, Black Market Baby… Éste era un lugar donde todo era posible, un lugar de reunión. El DC punk / harDCore no habría sucedido así sin él. Hubo dos períodos principales de transformación en la historia del DC punk, Madams Organ y lo que llamaron Revolution Summer. Era esencial.

Hubo un choque generacional en este espacio, ¿pero fue una forma de iniciarse en la política?.

Paul: Para algunos, definitivamente.

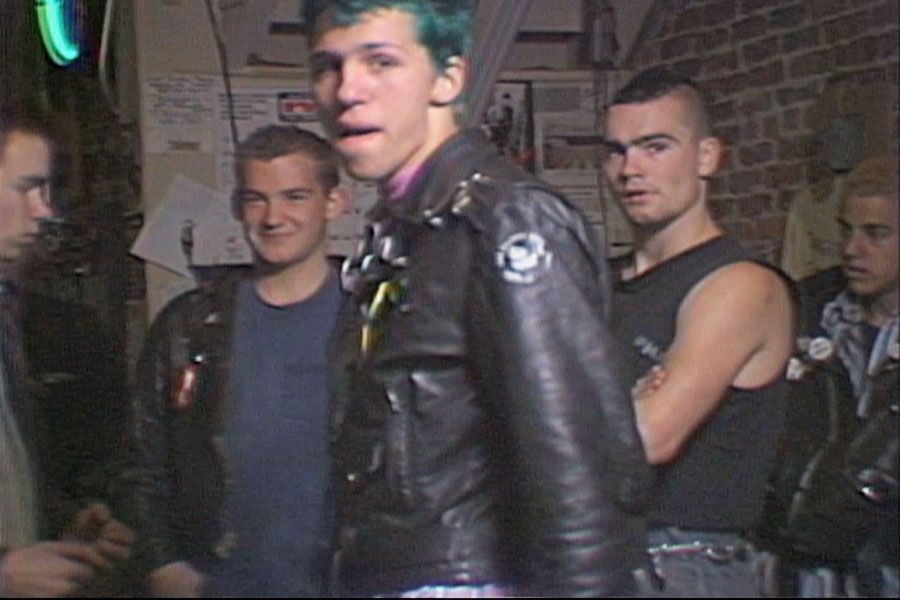

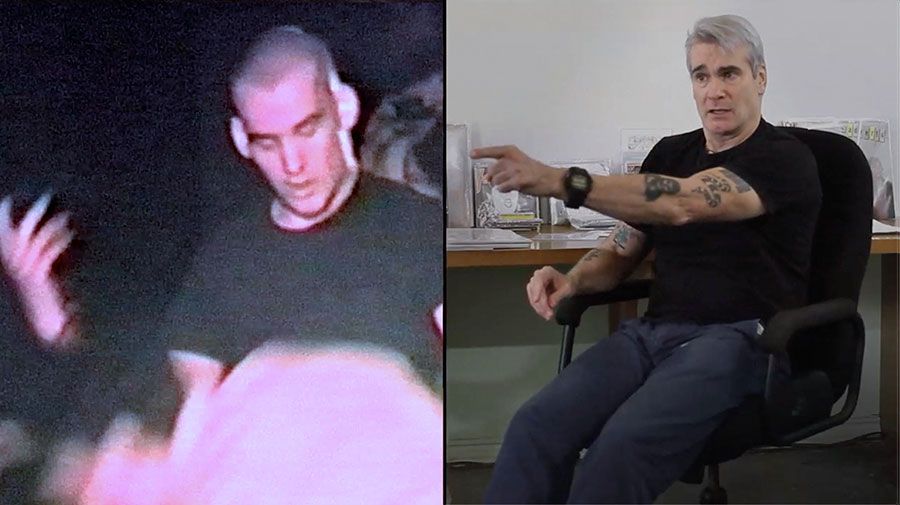

James: Es enormemente educativo tener entre 12 y 16 años, como Ian y Alec MacKaye y Henry Rollins y pasar 8 meses en ese espacio junto a hippies adultos, yippies, socialistas y comunistas. Cuando nos enfrentamos a diferentes estilos de vida e ideologías, también nos preguntamos a quién y qué representamos.

Y hablando de esto ¿Cómo era el activismo político en esa época?

Paul: En DC, la capital del imperio, el activismo me precede, como si siempre hubiera estado allí.

James: Era fascinante ver cómo el activismo estaba presente en la escena antes de 1985, el momento en que empecé a ir a conciertos. Era muy diferente la forma en que se expresaba en cada banda o en otras personas de la escena. Cuando era adolescente no estaba particularmente comprometido políticamente, me interesaba el periodismo, estar informado, y publiqué un artículo en la sección adolescente del Washington Post cuando tenía 16 años. Los conciertos que iban casi siempre tenía alguna connotación política; no sabía que los conciertos en otras ciudades no tenían discursos ideológicos entre los sets.

Minor Threat creó los estándares de lo que tenía que ser una banda de HC: velocidad, rabia, emoción (destilando todo lo que había en la escena). Viéndolos en perspectiva, ¿cuál crees que ha sido su aportación en la articulación de un discurso alrededor del punk?

James: Mientras estábamos editando, había dos temas sobre los que pensé que querría hacer toda una película: Madams Organ (no el nuevo que rescató el nombre) y Minor Threat. Ian tenía, y tiene, mucho que decir y todos eran músicos se tomaban su oficio muy en serio. Minor Threat estableció que el punk no se trataba de una rebelión per se, sino de una crítica constructivaque hace hueco para crear algo nuevo. Sus canciones, en conjunto, son como neuronas que conectan ideas que son de vital importancia hoy día.

Mucho se ha hablado del rol de la clase media en la creación del punk y del HC, una clase media como catalizadora de la cultura de la negación ¿Fue el HC una forma de denunciar sus privilegios?

James: Durante el período que cubre la película, no fue tanto el caso. La escena de finales de los años 70 estaba compuesta por personas de de orígenes muy diversos. Había una gran cantidad de personas cuyas familias eran de clase trabajadora, algunos de la clase media, unos pocos de la clase media alta… Pero, en general, es cierto que en su origen el DC punk no era una escena de clase trabajadora como lo fue en Inglaterra en un principio. También vale la pena señalar que la gran mayoría de la gente en la escena de DC tenían el apoyo o, al menos, la indiferencia de sus padres; pero fue una elección y se podría decir que una característica de lo que significa el punk, no guiarse por la ética egocéntrica del capitalismo.

¿Podríamos entender este documental como una historia del activismo comunitario?

James: Es casi una precuela. Personalmente, me hubiera gustado que estuviera más enfocada políticamente, pero la escena en ese momento no estaba tan unificada en torno a estos temas como lo estuvo a mediados de los años 80. La película de Robin Bell “Fuerza Positiva: más que un testigo” realmente cubre ese despertar de la conciencia política en la escena de DC.

[youtube width=’644′ height=’388′]ooY0yt03bMo[/youtube]

English:

PUNK THE CAPITAL. AN UNCONTROLLABLE ENERGY

Documenting requires order and preservation, perhaps the most valuable thing. And speaking of a phenomenon with such an opaque vocation as punk, this work is even more important. Let’s not forget that most of the expressions of punk tend to be hidden and many times tracing a clear genealogy of the process is hard. Thus, we often find ourselves with stories mutilated from many elements, mutilations that deprive us of a broader knowledge. That is why this documentary is important, a genuine work of archaeology, which presents punk as a polyphonic and vital energy.

The project of I am eye, a punk-inspired cinema forum, is very interesting. Was this to some extent the germ of this documentary?

James: James June Schneider: I’ll let Paul answer that one since he was behind the I am Eye film series.

Paul: I Am Eye was very much a do-it-yourself work flow and aesthetic. We wanted to provide a space to show and view films without judgement of curators or critics. Or a profit motive. If a person brought a film we would show it. Many filmmakers met and discussed among themselves. Over the years I showed many of my own films, diary/essay type films with flights of filmic fancy, not exactly fiction. Madams Organ where I spent a good deal of time was of course featured often.

During the 9 years it was working, how did it work?

James: We started collecting around the turn of the century and shooting some things when we could but only when I moved back from France in 2013 did we really start working on the film with intensity. That included the Kickstarter campaign. Our goal with this project was not only to make the film but also to preserve archives and somehow document the contributions of people in the music scene, so we filmed a lot more interviews than we needed for the film, around 100 interviews, each lasting between about 2 and 4 hours. Things like that were not part of finishing the film itself and inevitably wound up stretching out the process. For this kind of film, there are a lot of advantages to taking more time. And in general, I’d say we should have less films and better films – not to qualify our film but I can say we took the time we thought we needed. The vast majority of films have been forged by a capitalist sense of time.

Did you grow up with the Washington DC scene?

James: There were three main people working on the film, Paul Bishow, Sam Lavine, and myself. Sam and I grew up in the DC scene and both Sam and I have played in a number of bands. My worldview has been shaped by the DC scene. Paul moved to DC in 1979 and fell right into ground zero for the D.C. punk scene so he saw it grow up!

Paul: I was 27 when i came to in DC.

I am an eye had a strong political imprint. How was your political awareness process?

Paul: I was a member of the Worker’s League a Trotskyist party, 4th International or something. I used to sell a newspaper at rallies and protests (The Bulletin).

The documentary deals with the beginnings of punk and HC in Washington from 76 to 83. Why those particular years?

James: I’m intrigued by how movements take root, how communities come together for whatever moment they are fueling together. The DC punk scene started circa 1975-1976 at the same time as elsewhere and it was basically a steady and fast growth up until around 1983 when harDCore sort of imploded here. So we followed a few main groups up to that time, Slickee Boys, Bad Brains and Minor Threat, while touching a bunch of other groups along the way. We didn’t want to make a band by band film. Rather the film tells a story and that story reaches a good stopping point in 1983/1984.

What was so special about Washington DC that such a dynamic scene emerged from it?

James: DC still has a kind of backdrop of potential, there have been thrivingunderground movements but no dominating or imposing cultural history here. There is a lot that is just chance with these things but in DC’s case it was also a confluence of conditions. For starters there was a group of incredibly clear minded people in the mid-70s who built a solid foundation and wanted to see something happen, people like Kim Kane (Slickee Boys), Skip Groff (Yesterday and Today Records) and Howard Wuelfing (The Nurses and several fanzines). There were great bands coming up circa 1977-1979 and then the Bad Brains came in and set the bar so high. And on top of that of course was the founding of Dischord Records which incorporated ethics and a DIY approach that were already somewhat present in the fabric of the scene. That gave the scene legs and the rest is history!

Paul: It was not unique to DC, I think the whole rock world was ready. From it’s beginnings rock had ground up sensibility. By the late seventies the corporate element had become too much for many. The time was right to start over, ripe everywhere.

Many of the major cultural institutions are taking an interest in punk and its history, especially as it relates to the aesthetic legacy. To what extent do you think punk is assimilated? Has it become a museum piece?

James: DC punk has indeed become an object of study, and maybe some of the music is now canon, but it is far from dead. There are still lots of new bands, new ideas and non-musical punk things coming out of the larger DC scene. It no longer is something that stays in DC either, it’s infused into popular culture, “high” art, politics (think presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke), you name it.

Paul: I used to think that once things were in a museum it was over, but after 16 years working with the Smithsonian museums, I now see the point. I like the dynamic of history as a living thing (organic).

Bad Brains was a major group in the genesis of HC. Do you think they have received the recognition they deserve?

Paul: The first time I saw the Bad Brains we did not have the term hardcore. They were clearly the best band. To this day I hear them referred to as “The Best Hardcore Band Ever” so the answer is yes!

It is necessary to have a physical space for a scene to grow. What role did the Madam’s Organ play in this one?

Paul: It certainly helps!

James: For the Bad Brains and the kids who would start Minor Threat a few months after Madams Organ closed, Scream, Black Market Baby… this was a place where everything was possible, it was a hangout. DC punk / harDCore wouldn’t have happened like it did without it. There were two main transformative periods in DC punk history, Madams Organ and what they called Revolution Summer. It was essential.

There was a generational clash in this space, but was it a way of getting started in politics?

Paul: For some definitely.

James: It’s hugely formative to be 12-16 years old, like Ian and Alec MacKaye, Henry Rollins, and to spend 8 months hanging out in that space alongside adult hippies, yippies, socialists and communists. When we are confronted by different lifestyles and ideologies, we question who and what we stand for as well.

And speaking of this, what was political activism like at that time?

Paul: In DC, the capital of the empire, the activism predates me, almost as if it was always here.

James: It was fascinating to see how activism was present in the scene before 1985, the moment when I started going to shows. It just was very different how it was expressed by each band or other people in the scene. As a teenager I was not particularly politically engaged, I was interested in journalism, staying tuned in, and had an article in the Washington Post teenage section when I was 16 years old. The concerts I attended almost always had some political angle. I didn’t know that concerts in other towns didn’t have political speeches in between sets.

Minor Threat created the standards of what an HC band had to be: speed, rage, emotion (distilling everything from the scene). Looking at them in perspective, what do you think has been their contribution to the articulation of a discourse around punk?

James: While we were editing, there were two subjects I thought I would want to make a whole film about, Madams Organ (not the new one that took the name) and Minor Threat. Ian had and has a lot to say and they were all such intense musicians who took their craft so seriously. It was also their time. Minor Threat established that punk was not about rebellion per-se, it was a constructive dismissal, making space for building something new. Their songs cumulatively are like neurons that connect so many ideas that are every bit as important today.

Much has been said about the role of the middle class in the creation of punk and HC, a middle class as a catalyst of the culture of denial. Was HC a way of denouncing its privileges?

James: During the period that we cover in the film, that wasn’t as much the case. The late 1970s scene was composed of people from a wide range of backgrounds. There were a fair amount of people whose families were from the working class, some from the middle class, a few from the upper middle class. But in general it’s true that at its root, DC punk was not a working class scene like it was in England in the beginning. It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of people in the D.C. scene had the support or at least the indifference of their parents. But it was a choice and one might say a characteristic of what punk means, not to be guided by the self-centered ethics of capitalism.

Could we understand this documentary as a story of community activism?

James: It’s almost a prequel, I personally would have liked for it to be more politically oriented but the scene at that time was not as unified around issues as it became in the mid-1980’s. Robin Bell’s film “Positive Force: More than a Witness” really covers that awakening of a political consciousness in the D.C. scene.