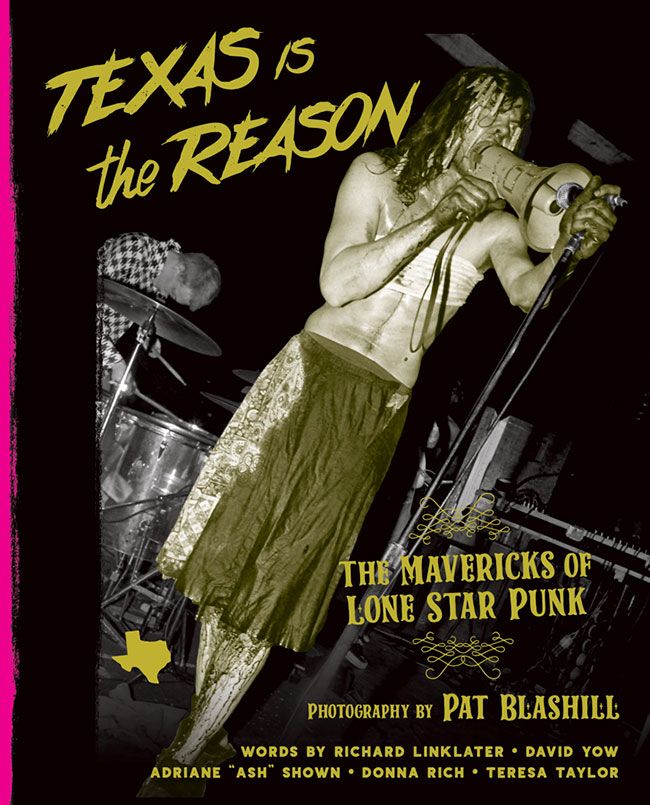

{english below} Fotógrafo de la incipiente escena punk en Texas, nos trae un libro con más de 200 fotografías que respiran energía y que lleva por titulo “TEXAS IS THE REASON: THE MAVERICKS OF LONE STAR PUNK”. La verdad es que el punk siempre ha echado raíces en los lugares más insospechados; Texas es unos de estos sitios que a priori no parecen los más adecuados, pero es donde agarran con más fuerza. Si algo caracteriza al punk es el no aceptar el statu quo y, desde luego,Texas es un buen campo de batalla.

Siempre se ha relacionado el inicio del punk y el HC como una reacción a Reagan ¿Cómo era la situación social en Texas en aquella época?

Los punks de Texas estaban furiosos por lo de Reagan, pero también desafiaban el racismo local, la homofobia y el conservadurismo religioso. Texas era (y sigue siendo) muy conservadora políticamente, aunque Austin es una pequeña isla liberal en medio de ella. Gary Floyd de los Dicks me dijo que estaban muy molestos por la violencia policial y el terrorismo del KKK, pero los mismos Dicks eran bastante intimidantes y aterradores. Otras bandas eran menos abiertamente políticas, pero la mayoría de nosotros teníamos la actitud: “Jodeos, somos de Texas”.

¿Cómo era la escena punk en ese momento en Texas?

El punk de Texas, especialmente la escena de Austin, era salvaje y de estilo abierto. En 1982, ninguna de las bandas sonaba como las demás y, la mayoría de ellas, no sonaban como ninguna otra banda de cualquier lugar. También era muy gay, muchas de las bandas estaban lideradas por hombres o mujeres abiertamente gays. Todo estaba permitido, o al menos la gente lo sentía así. Los tejanos que habían llegado a Austin desde ciudades más pequeñas, como Killeen o Gladewater, sentían que tenían permiso para volverse locos, y así era.

Leí que fue tu padre el que te proporcionó la primera cámara, ¿mostraste interés en la fotografía desde muy joven?

Bueno, mi padre era un fotógrafo aficionado y me dio una cámara Kodak cuando era joven, sí. Me entusiasmaba tomar fotos, pero sobre todo de una manera un poco “nerd” en general.

En una primera vista a tu trabajo vemos una fuerte influencia de Robert Frank (me refiero a Los Americanos) ¿Qué fue lo que te atrajo de su trabajo?

Cuando vi por primera vez las fotos de Robert Frank, me di cuenta de que la fotografía no se trataba sólo de fotos bonitas. Ya había empezado a escuchar bandas más raras y oscuras, como Roxy Music, pero hasta entonces no había visto ninguna fotografía que mostrara un lado más oscuro de la vida. Sigo pensando que sus fotografías son valientes, honestas, misteriosas y hermosas al mismo tiempo.

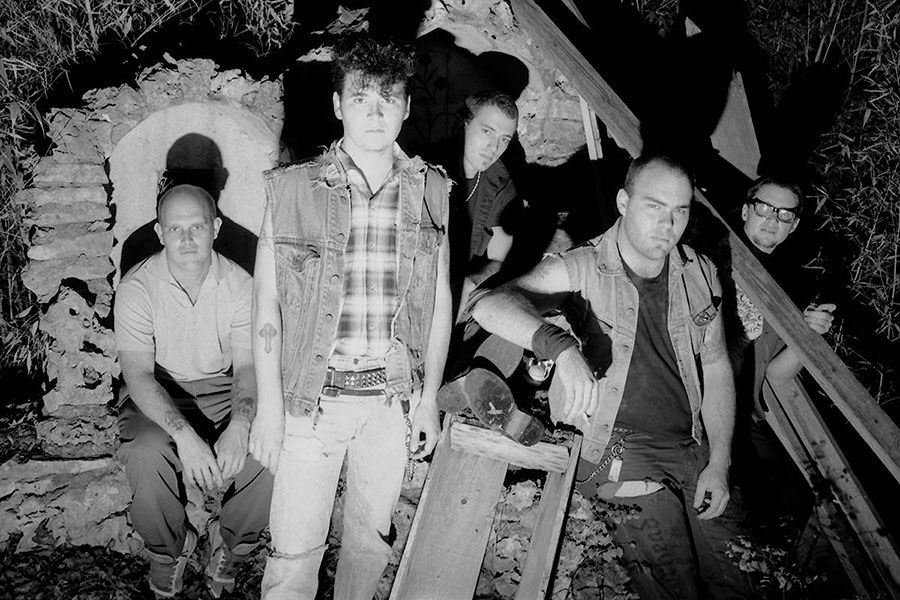

Poison 13

¿Cómo crees que adaptaste su influencia a tu fotografía?

Tal vez Frank me liberaba de la misma manera que el punk rock era (y sigue siendo) liberador para algunos músicos: me mostró que el enfoque, el desenfoque y la técnica en general no eran tan importantes como esperar un momento que contara una historia o evocara algún sentimiento fuerte. Después de descubrir a Frank, empecé a prestar atención a todo tipo de grandes fotógrafos, sobre todo en la tradición del documental: Danny Lyon, Walker Evans, Diane Arbus y Mary Ellen Mark, pero también Man Ray y Andre Kertesz.

En tus fotografías la composición es muy importante , es como si todo el mundo girara alrededor de tu cámara, ¿esto se debe también a tu aprendizaje de Robert Frank?

La fotografía se trata de organizar la información dentro de las cuatro líneas del marco. Frank y todos esos otros fotógrafos definitivamente me influenciaron; aprendí mucho de mis profesores en la Universidad de Texas, uno de los cuales me dijo que, cuando estás en algún lugar fotografiando, debes tratar de ponerte en un buen lugar, y luego dejar que las cosas sucedan frente a ti. También me encantó lo que dijo Robert Capa, el legendario fotógrafo de guerra: “Si tus fotos no son buenas, acércate a la acción”. Es un gran consejo, pero lo más interesante es que también fue lo que mató a Capa.

JJ Jacobson & Tony Johnson. The Offenders

¿Cuál ha sido tu formación fotográfica y qué has aprendido de ella?

Fui el fotógrafo del anuario del instituto y aprendí que no importa lo que digan los jóvenes, a la mayoría de ellos les gusta que les hagan fotos. En la universidad aprendí protocolos de actuación, como siempre dar a la gente que sale en tus fotos copias de las mismas más tarde. Tuve grandes maestros, pero probablemente aprendí más, especialmente sobre composición, mirando enormes montones de libros de fotos en la biblioteca pública de Austin.

Técnicamente muchas de tus fotos están compuestas por un mismo diálogo que se da entre diferentes planos (sobre todos en las fotos del público), ¿qué es lo que quieres transmitir?

Me interesa el intercambio entre personas, aunque no sea una foto de conciertos. Estoy convencido de que, en cualquier escena, todos juegan un papel, todos son importantes. En el punk de Texas, incluso los skin heads nazis eran importantes, aunque yo odiaba a la mayoría de ellos. Así que creo que mis fotografías más exitosas son aquellas en las que he podido capturar esa danza de gestos, afecto, violencia y camaradería.

¿Este tipo de registros fragmentarios ayuda a dar más intensidad a las imágenes?

No puedo responder a eso. Estoy seguro de que algunas personas no encontrarán mis fotos intensas en absoluto, y a algunos les gustarán las fotos que no me importan tanto, así que todo es bastante subjetivo. Para mí, la intensidad de cualquier fotografía viene de la emoción y la relación entre el fotógrafo y el sujeto.

Mucha de la fotografía documental actual, sobre todo la fotografía musical, se ha vuelto muy estándar ¿a qué crees que se debe este estancamiento?

No estoy seguro de que el número de fotógrafos realmente excelentes haya disminuido, pero el número de fotógrafos competentes y técnicamente elegantes se ha disparado. Simplemente es más fácil hacer buenas fotos ahora, pero siguen siendo sólo los mejores los que hacen fotos con alma. Mucha de la fotografía musical es como la fotografía de deportes, tiene mucha energía, pero se ve como todo lo demás. Y fíjate en cómo algunas personas elogian una “buena” foto, la llaman “una gran captura”, pero la fotografía nunca se ha limitado a capturar o documentar algo, las buenas fotografías suelen ser sobre la intuición, los accidentes y el vudú.

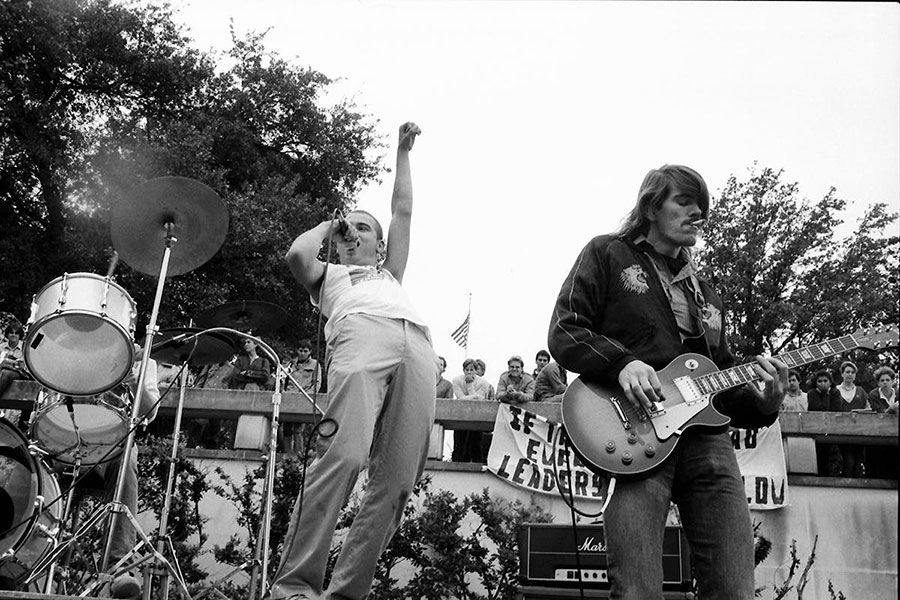

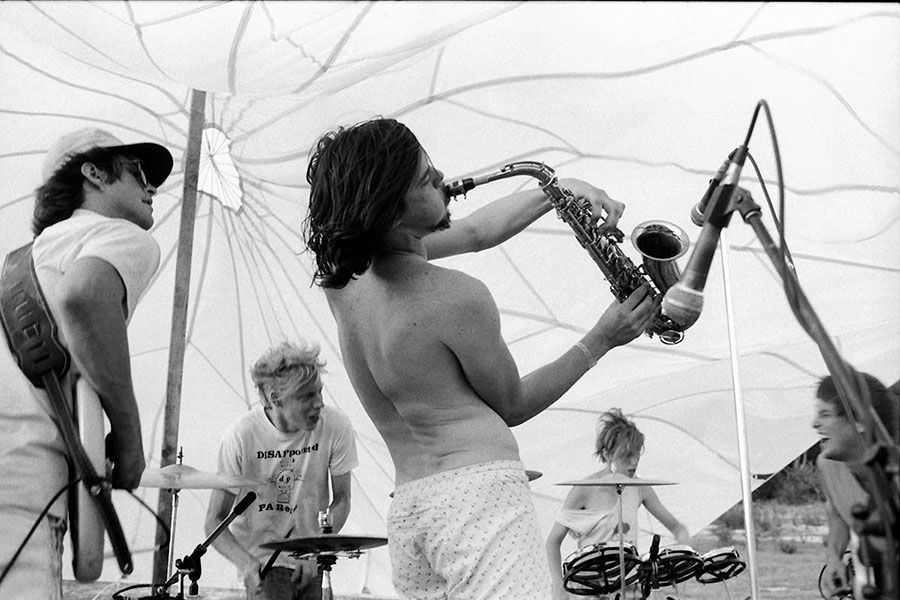

Butthole Surfers

¿ Que fotógrafos actuales te interesan?

Me encantan las fotos de Mike Brodie de jóvenes vagabundos y punks crust, es magnífico y muy profundo. En la misma línea, mi viejo amigo Bill Daniel está haciendo un excelente trabajo fotografiando la nación DIY de artistas underground, anarquistas y nómadas americanos; acaba de publicar un gran libro llamado Tri-X Noise. También me gusta Infidel, el libro de Tim Hetherington de fotografías de soldados estadounidenses en Afganistán. En cuanto a la fotografía de música en vivo, no conozco a nadie que haya superado las fotos de Charles Peterson de Seattle a principios de los noventa.

Hablemos un poco de equipo fotográfico, ¿sigues disparando con película?

Lo hago, pero no con la suficiente frecuencia. Sigo usando la misma configuración que usé para las fotos de Texas is the reason: mi vieja Canon F-1, un flash Vivitar 283 y una película Tri-X. Mi club favorito en Viena se llama Venster 99, es un pequeño y oscuro agujero con cervezas baratas y un escenario muy bajo, condiciones ideales para la música y fotos del punk rock. También hago fotos con mi iPhone y tengo una buena 35 mm digital, y una amiga me ha prestado la Leica de su suegro de los años 50, pero me llevará otro par de décadas dominarla…

Sammy Fang

¿Cuáles son tus objetivos favoritos?

Prefiero mis objetivos de 35 mm y 28 mm. Siempre he odiado los teleobjetivos, e incluso un 50 mm “normal” me parece estrecho y claustrofóbico.

En tu faceta de periodista musical, ¿qué piensas que debe tener una buena entrevista?

Oh, tantas cosas… Quiero decir, la persona que hace las preguntas tiene que estar bien preparada y es ciertamente más agradable si los participantes muestran algo de respeto entre ellos, pero las entrevistas súper polémicas y desagradables también son muy entretenidas de leer. No soy polémico como periodista, me gusta pensar que soy duro pero justo, trato de no hacer llorar a la gente. Una de mis entrevistas favoritas fue con Iggy Pop, era súper elocuente, amable, divertido e inteligente; en un momento dado le pregunté algo poco acertado y sospecho que herí sus sentimientos, se puso un poco pálido y dijo: “No tengo que responder a eso”. Me sentí como un idiota, luego seguimos adelante y nos reímos un poco más ¡Esa fue una buena entrevista!

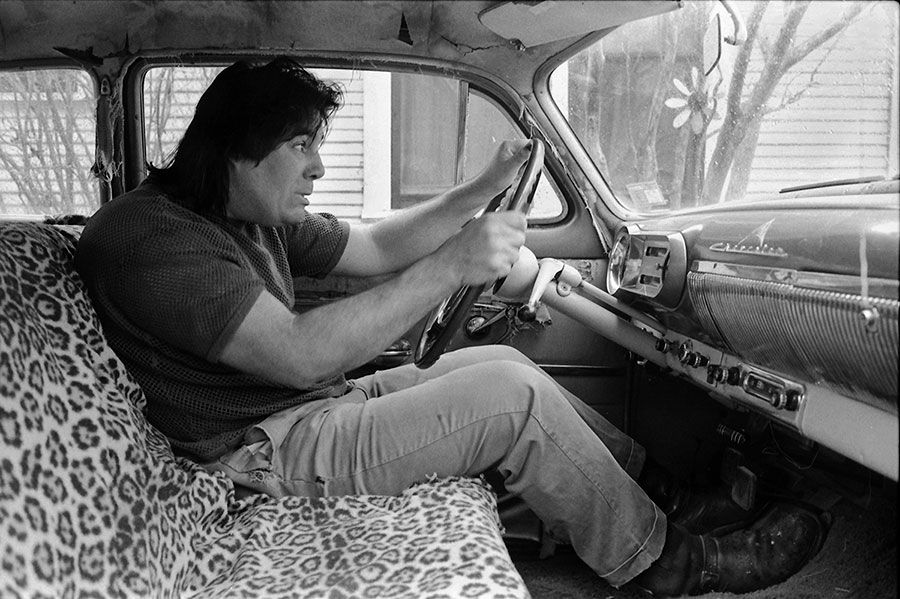

Biscuit en su Chevy del 57. Invierno 1984

Lynda Stuart

Butthole Surfers. Invierno 1987

English:

PAT BLASHILL. FIGHTING BACK

Photographer of the fledgling punk scene in Texas, brings us a book with over 200 photographs that exude energy. The truth is that punk has always taken root in the most unsuspected places. Texas is one of those places that a priori doesn’t seem to be the most suitable, but it’s where they grab hold of the most; if there’s one thing that characterizes punk, it’s not accepting the status quo. And, of course, Texas is a good battlefield.

The beginning of punk and HC has always been related as a reaction to Reagan. What was the social situation in Texas at that time?

Punks in Texas were angry about Reagan, but also very defiant of local racism, homophobia and religious conservatism. Texas was (and still is) very conservative politically, although Austin is a little liberal island in the middle of it. Gary Floyd of the Dicks told me that they were really pissed off about police violence and the terrorism of the KKK, but the Dicks themselves were pretty intimidating and scary. Other bands were less overtly political, but most of us had an attitude: “Fuck you, we’re from Texas”.

What was the punk scene like at that time in Texas?

Texas punk, especially the Austin scene, was wild and wide open stylistically. By 1982, none of the bands sounded like each other, and most of them didn’t sound like any bands anywhere. It was also very gay—many of the bands were fronted by openly gay men or women. Everything was permitted, or at least people felt that way. Texans who had come to Austin from smaller towns, like Killeen or Gladewater, felt like they had permission to go nuts, and they did.

I read that it was your father who provided you with the first camera, did you show an interest in photography from a very young age?

Well, my pops was an amateur photographer, and he gave me a Kodak camera when I was young, yes. I was enthusiastic about taking pictures, but mostly just in a general nerdy way.

In a first look at your work we see a strong influence of Robert Frank (I mean the American). What attracted you to his work?

When I first saw Robert Frank’s pictures, I realized photography wasn’t just about pretty pictures. I had already started listening to weirder, darker bands, like Roxy Music, but until then, I hadn’t seen any photography that showed a darker side of life. I still think his photographs are gritty, honest, mysterious and gorgeous, all at the same time.

How do you think you adapted his influence to your photography?

Maybe Frank was liberating to me in the same way that punk rock was (and still is) liberating for some musicians: he showed me that focus, blur and technique in general were not as important as waiting for a moment that told a story or evoked some strong feeling. After discovering Frank, I started looking at all sorts of other great photographers, mostly in the documentary tradition: Danny Lyon, Walker Evans, Diane Arbus and Mary Ellen Mark, but also Man Ray and Andre Kertesz.

In your photographs the composition is very important, it is as if the whole world revolved around your camera, is this also a learning from Robert Frank?

Photography is about organizing information within the four lines of the frame. Frank and all of those other photographers definitely influenced me. I learned a lot from my teachers at the University of Texas, one of whom told me that when you are out somewhere shooting, you should try to put yourself in a good place, and then just let things happen in front of you. I also loved what Robert Capa, the legendary war photographer, said: “If your pictures aren’t any good, get closer (to the action.)” That’s great advice, but interestingly enough, it’s also what got Capa killed!

What has been your photographic training and what have you learned from it?

I was a photographer for my high school yearbook, and I learned that no matter what young people say, most of them like having their picture taken. At university, I learned respectful practices, like always giving the people in your pictures copies of the pictures later. I had great teachers, but I probably learned the most—especially about composition—from looking at huge stacks of photobooks at the Austin public library.

Technically, many of your photos are composed by the same dialogue that occurs between different shots (especially in the photos of the public), what do you want to convey?

I’m interested in the exchange between people, even if it’s not a performance photo. I’m convinced that in any scene, everyone plays a role, everyone is important. In Texas punk, even the Nazi skinheads were important, even though I hated most of them. So I think my most successful photographs are the ones where I’ve been able to capture that dance of gesture, affection, violence and camaraderie.

Does this kind of fragmentary registers help to give more intensity to the images?

I can’t answer that. I’m sure some people will not find my pictures intense at all, and some will like pictures I don’t care about that much, so it’s all pretty subjective. For me, the intensity of any photograph comes from emotion and the rapport between the photographer and the subject.

Much of today’s documentary photography, especially music photography, has become very standard. What do you think this stagnation is about?

I’m not sure the number of really superb photographers has decreased, but the number of competent, technically fancy photographers has exploded. It’s simply easier to make pretty good photos now. But it’s still only the best who make pictures with soul. A lot of music photography is like sports photography—it’s got plenty of energy, but it looks like everything else. And listen to how some people praise a “good” photo—they call it a “great capture.” But photography has never just been about capturing or documenting something. Good photographs are usually about intuition, accidents, and voodoo.

Which current photographers interest you?

I love Mike Brodie’s pictures of young hobos and crust punks—it’s gorgeous and very deeply felt. Along the same lines, my old friend Bill Daniel is doing excellent work photographing the DIY nation of American underground artists, anarchists and nomads. He just put out a great book called Tri-X Noise. I also like Infidel, Tim Hetherington’s book of pictures of US soldiers in Afghanistan. As for live music photography, I’m not aware of anyone who has topped Charles Peterson’s pictures of Seattle in the early nineties.

Let’s talk about photographic equipment, do you still shoot with film?

I do, but not nearly often enough. I still use the same set-up that I used for the pictures in Texas Is The Reason: my old Canon F-1, a Vivitar 283 flash and Tri-X film. My favorite club in Vienna is called Venster 99, and it’s just a dark little hole with cheap beers and a very low stage—ideal conditions for punk rock music and pictures.

I also take pictures with my iPhone, and I have a good digital 35 mm too. And a friend has loaned me her father-in-law’s Leica from the 1950s, but that will take me another couple of decades to master…..

What are your favorite lenses?

I prefer my 35mm and 28mm lenses. I’ve always hated telephoto lenses, and even a “normal” 50 mm feels cramped and claustrophobic to me.

In your role as a music journalist, what do you think makes a good interview?

Oh, so many things. I mean, the person asking questions has to be well-prepared and it’s certainly more pleasant if the participants show some respect to each other. But super confrontational, nasty interviews are very entertaining to read, too. I am not confrontational as a journalist—I like to think of myself as tough but fair. I try not to make people cry. One of my favorite interviews was with Iggy Pop. He was super articulate, gracious, funny and smart. At one point, I asked him something mean, and I suspect it hurt his feelings. He just blanched a little bit and said, “I don’t have to answer that.” I felt like a jerk. Then we moved on and had some more laffs. That was a good interview!