{english below} Mike Sniper, fundador de Captured Tracks, es una figura fundamental en la escena musical independiente. Desde su creación en 2008, Captured Tracks ha sido hogar de artistas como Mac DeMarco, DIIV, Wild Nothing, y muchos más, siendo clave en la evolución de la música alternativa en los últimos años. En esta entrevista, Sniper nos comparte su perspectiva sobre la escena musical de Nueva York, su enfoque hacia la música independiente y el impacto de la digitalización en la industria. A lo largo de su carrera, ha logrado equilibrar el arte con el negocio, enfrentándose a desafíos propios del crecimiento de un sello independiente en un contexto cambiante. A través de su visión única y su enfoque personal, Sniper continúa siendo una de las voces más relevantes en el panorama de la música alternativa, con un ojo siempre en el futuro y un compromiso inquebrantable con los artistas que forman parte de su sello.

mike sniper

Mike, eres de Nueva York, una ciudad conocida por su vibrante escena alternativa. ¿Cómo crees que la cultura alternativa en Nueva York en los 80 y 90 influyó en tus primeros intereses musicales y en tu carrera como creador de Captured Tracks?

En realidad nací y crecí en Nueva Jersey, en la costa de Jersey, como en el horrible programa de televisión. La gente que es de allí no tiene realmente ese acento ni actúa como esos repugnantes idiotas, los llamábamos “Bennies” porque cruzaban el puente Ben Franklin para llegar a la costa desde sus casas en el norte de Nueva Jersey, Staten Island, Filadelfia, etc. No digo que toda la gente de allí sea mala, pero el tipo de personas que se sentía atraído por Seaside Heights era deplorable. Crecí muy lejos de la cultura de Nueva York y solo leía sobre ella junto con un pequeño grupo de adolescentes afines de mi zona. Mi influencia fue tratar de evitar la horrible ciudad y la gente en la que crecí y un deseo de salir de allí lo antes posible, lo que ocurrió en 1996 cuando me mudé a Nueva York para estudiar. Por esa época, Jungle y Drum and Bass estaban en auge, y no mucha gente, ni siquiera en Nueva York, estaba en lo que yo estaba. Era la época de los “Club Kids”. Cualquier vestigio de Punk/Post-Punk/No-Wave y “rock indie” estaba prácticamente desaparecido por un tiempo. Así que, para hacer una historia corta, solo sé sobre los supuestos días de gloria de Nueva York desde lejos, a través de la colección de discos y la lectura. En cuanto a todo lo anterior a los 2000.

craft spells

diiv

A lo largo de los años, Nueva York ha sido un epicentro de diversos movimientos artísticos y musicales, desde el punk y el no wave hasta la actual escena indie. ¿Cómo ha cambiado la escena alternativa de la ciudad desde tus primeros días en ella?

Ya no hay jóvenes que hagan buena música que puedan permitirse vivir aquí. Hay personas como yo que hemos vivido aquí el tiempo suficiente y hemos tenido éxito para poder vivir aquí, pero los jóvenes que viven aquí probablemente estén demasiado preocupados por sobrevivir y hacer frente a sus gastos como para dedicar tiempo a crear música, a menos que sean “nepo-babies”, supongo. Muchos jóvenes se han mudado a lugares como Brattleboro, VT y Asbury Park, NJ, para poder permitirse vivir mientras giran, escriben o graban. No creo que haya habido una gran escena aquí desde que todos los espacios de “DIY” cerraron hace unos 10-15 años. Aparte de eso, la mayoría de la música ahora se escribe en Ableton o en otro software por una sola persona, así que realmente no importa dónde vivas o si hay una escena. Cualquier escena no está basada en la ubicación, es un colectivo de algoritmos de “sounds similar” de Bandcamp/SoundCloud.

Mi sugerencia para la gente que quiera formar una banda (lo cual sería algo bueno, escribir y editar material con otras personas en lugar de ser un monolito): no se muden a Nueva York.

Hoy en día, las plataformas digitales y las redes sociales han cambiado la manera en que la cultura alternativa se desarrolla en todo el mundo, incluida Nueva York. ¿Cómo crees que las redes sociales y la digitalización han impactado la escena cultural de la ciudad, especialmente en comparación con la era preinternet que viviste al inicio de tu carrera?

Internet ya existía al comienzo de mi carrera. Creo que las redes sociales y la digitalización de las subculturas/arte han afectado todo de la misma manera que a todo el mundo. Uno pensaría que, con las infinitas opciones para escuchar música y la increíble facilidad de poner tu arte en una plataforma para que la gente lo escuche o lo vea, todo el mundo seguiría escuchando y gustándole la misma mierda. Es más un testimonio de los problemas con el control populista del arte que de algún problema con la tecnología. Por mucho que hubiera sido genial que todo lo disponible al alcance de todos hubiera creado toneladas de música increíble, todo el mundo escucha las mismas 10 canciones y todas son poco desafiantes, aparte de las microculturas que son tan específicas que ya no se conectan entre sí como solían hacerlo (ver: post-disco y no wave) porque ahora puedes ir a encontrar tu comunidad online con tus gustos exactos. Ya no hay influencias cruzadas ni los brazos abiertos de cualquier crítica/publicación musical que aún abrace la música comercial, incluso en la esfera indie, en lugar de arriesgarse a hacer algo diferente. Es miserable. Lo que siembras cosechas.

Mike, en los primeros días de Captured Tracks, lanzaste discos de bandas como Dum Dum Girls, Woods y Thee Oh Sees. ¿Cómo descubriste estos grupos?

Todos eran amigos, les estaba pidiendo favores.

Antes de fundar Captured Tracks, trabajaste en tiendas de discos y como diseñador freelance. En una entrevista mencionaste que la mayoría de los sellos exitosos están dirigidos por personas con experiencia en tiendas de discos, no necesariamente por aquellos que han estudiado la industria musical. ¿Podrías explicar cómo tu experiencia en las tiendas de discos te preparó para dirigir Captured Tracks?

Sí, fácil. Cuando trabajas en una tienda de discos, escuchas música 8 horas al día y hablas de música 8 horas al día, en su mayoría música que nunca escucharías por tu cuenta, y tienes conversaciones reveladoras con personas apasionadas. No veo esa clase de pasión en las personas que salen de los programas de la industria musical. Una vez di una charla en NYU para estudiantes y todos estaban mirando sus relojes esperando que terminara, excepto uno o dos. Me he dado cuenta de que es más común fuera de los EE.UU. que las personas que trabajan en sellos de música independiente tengan una formación más estructurada y ‘dogmática’. Es por eso que, en muchos casos, en otros países es más común que el manager o el abogado se involucren antes de que se hable con los sellos discográficos, mientras que en los EE.UU. se suele dar más importancia a la creatividad y a las conexiones informales.

Sabemos que Captured Tracks comenzó con un enfoque muy “DIY”. ¿Hubo algún momento en que te sintieras abrumado por las responsabilidades del sello y cómo lograste mantener la independencia mientras escalabas el proyecto?

Pregunta uno: No. Pregunta dos: Contratar a personas cualificadas y apasionadas para que los artistas vean que estás escalando al mismo ritmo que ellos se hacen más populares.

Capturaste la esencia de la escena musical independiente de Nueva York en la década de 2010. ¿Cómo describirías la atmósfera creativa de la ciudad durante ese período?

Básicamente ya estaba muerta en ese punto, solo que nadie lo sabía aún.

Durante los primeros años de Captured Tracks, ¿hubo algún fracaso o momento difícil que consideres crucial para el crecimiento del sello? ¿Cómo lo superaste y qué aprendiste de ese desafío?

Sí, creo que cualquier pequeña empresa, sin importar la industria, pasa por períodos estresantes de crecimiento. Para un sello discográfico, es difícil escalar sin un catálogo de discos. Es simplemente reinvertir todo, sin dinero extra o ahorros. Eso lleva a un peligro financiero. Ahora tenemos un catálogo lo suficientemente fuerte como para que ya no sea una preocupación, supongo que la mayor hazaña que puedes lograr que realmente te ayuda es simplemente existir y sobrevivir lo suficiente como para no estar al borde del colapso total en todo momento.

El mundo de la música independiente ha cambiado mucho desde que empezaste. Mirando atrás, ¿hay algo que hubieras hecho de manera diferente con el sello?

No.

Mencionaste que algunos de los primeros lanzamientos eran más un juego que una estrategia empresarial. Con el tiempo, ¿cómo cambió tu enfoque hacia la industria musical y cómo equilibras lo comercial con lo artístico?

No lo hice, así que tuve que contratar a personas que lo hicieran. Si todavía estuviera a cargo de esas cosas, cada lanzamiento estaría perdiendo dinero. La mayoría de lo que escucho no sería posible de lanzar en el estado actual del sello.

Captured Tracks ha mantenido una estética visual consistente a lo largo de sus lanzamientos. ¿Cómo colaboras con los artistas y diseñadores para crear portadas de álbumes que complementen la música y refuercen la identidad del sello?

No estoy del todo de acuerdo con esto. Viniendo de una formación en la escuela de arte, contribuí mucho más en los primeros discos, junto con nuestro diseñador interno Ryan McCardle. Después de un tiempo, los managers/artistas/otros ya no quieren tu opinión, “la hierba siempre parece más verde en el otro lado”, como decimos aquí. Ya no creo que tengamos una estética visual coherente, es más o menos aleatoria.

soft moon

wild nothing

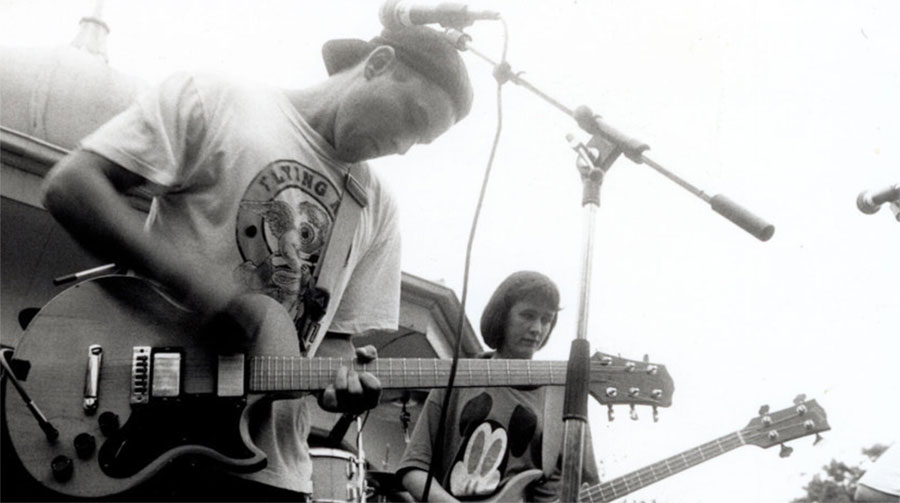

Tu relación con Flying Nun y la reedición de discos clásicos ha sido un pilar importante. ¿Qué es lo que más valoras de estas reediciones y cómo impactan en tu visión de preservar el legado musical a través de Captured Tracks?

Era un gran fan de Flying Nun. El alcance de lo que queríamos hacer… no llegamos a ello. Mucho tiene que ver con los derechos que Flying Nun tenía o no tenía sobre mucha de la música en su catálogo. Sacamos a los artistas conocidos como The Chills y The Verlaines con la esperanza de hacer el trabajo con los discos más oscuros después, pero terminó siendo reeditado en sellos más pequeños. Aún hacemos muchas reediciones, pero ahora es mucho más fácil trabajar de uno a uno con el artista en lugar de hacerlo a través de un tercero, por genial que sea Flying Nun y su personal. Solo que hay mucha burocracia. El legado musical de Captured Tracks no es algo en lo que piense tanto como antes. Ahora se trata más de los artistas y de ayudarles a lograr sus objetivos. Tal vez esos primeros 5 años sean el legado de manera coherente, ahora estamos aquí para ayudar a los que trabajamos más que para preocuparnos por la marca. Me encantan los sellos, sigo siendo fan de los nuevos y compro todos sus lanzamientos, pero al mundo ya no parece importarle. Recuerdo esto cuando Pitchfork dejó de poner el nombre del sello en negrita en sus reseñas y dejó de anunciar las firmas de los sellos, solo “el artista anuncia un nuevo disco”, como si el disco hubiera salido sin sello, lo cual, de hecho, es a menudo el caso ahora. Siento que firmar con un sello distinguido ya no es el sueño que era en el pasado.

the servants

Has visto a muchas bandas desde sus etapas iniciales. ¿Hay alguna historia o anécdota sobre un artista que firmaste cuando aún no eran conocidos que te haya marcado o te recuerde por qué haces lo que haces?

Solía emocionarme cuando firmábamos a un artista desconocido y luego, en un año, llenaban un lugar como el Bowery Ballroom. Eso sería un buen cierre para el “Capítulo Uno” de trabajar con alguien durante un tiempo. Ahora, en su mayoría, firmas bandas que ya tienen un lanzamiento propio exitoso y oyentes mensuales o lo que sea, así que es difícil elegir un momento, es más bien un impulso constante.

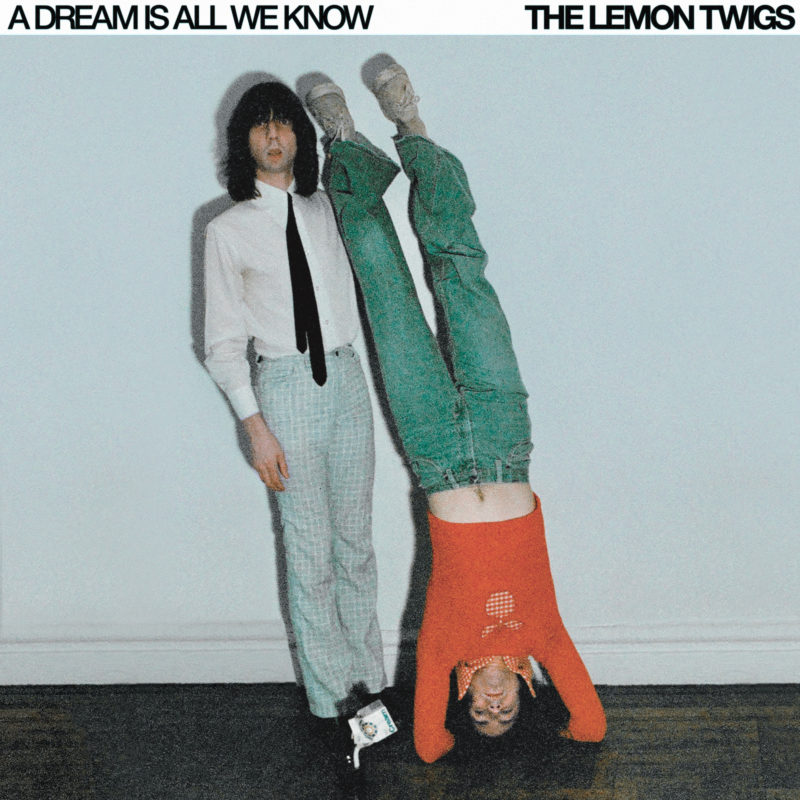

the lemon twigs

Con el auge de las plataformas de streaming y la digitalización de la música, ¿cómo ha adaptado Captured Tracks sus estrategias de distribución y marketing para llegar a una audiencia más amplia?

La gente reacciona positivamente a la buena música y odia la música mala. Esta es la filosofía total de mi marketing.

Mirando al futuro, ¿qué cambios en la industria musical te emocionan, y cómo planeas que Captured Tracks se adapte a ellos?

Oh dios, nada. ¿Hay cambios de los que emocionarse?

blouse

able tasmans

/

/

/

English

MIKE SNIPER. THE MAN BEHIND CAPTURED TRACKS AND THE SHIFT OF INDEPENDENT MUSIC.

Mike Sniper, founder of Captured Tracks, is a key figure in the independent music scene. Since its creation in 2008, Captured Tracks has been home to artists like Mac DeMarco, DIIV, Wild Nothing, and many more, playing a crucial role in the evolution of alternative music in recent years. In this interview, Sniper shares his perspective on the New York music scene, his approach to independent music, and the impact of digitalization on the industry. Throughout his career, he has managed to balance art with business, facing the challenges that come with growing an independent label in a changing landscape. Through his unique vision and personal approach, Sniper continues to be one of the most relevant voices in the alternative music scene, always keeping an eye on the future and maintaining an unwavering commitment to the artists that are part of his label.

Mike, you are from New York, a city known for its vibrant alternative scene. How do you think the alternative culture in New York in the 80s and 90s influenced your early musical interests and your career as the creator of Captured Tracks?

I was actually born and raised in New Jersey and grew up on the Jersey Shore, like the terrible reality show. People who are from there don’t actually have that accent or act like those repugnant idiots, we called them “Bennies” as they’d take the Ben Franklin Bridge to get to the Shore from their respective homes in North Jersey, Staten Island, Philly, etc. Not saying people from there are all bad, but the kind that was attracted to Seaside Heights were deplorable. I grew up well outside the culture of NYC and only read about it along with the small cluster of likeminded teens from my area. My influence was trying to avoid the horrible town/people I grew up in and a desire to get out of there as soon as possible, which was in 1996 when I moved to NYC for college. Around that time, Jungle and Drum and Bass were huge, not many people, even in NYC, were into what I was into, it was very much the “Club Kid” era. Any remnants of Punk/Post-Punk/No-Wave and “indie rock” was pretty much non-existent for a while. So, to make a short story long, I only know about the supposed Glory Days of NYC from afar via record collecting and reading. as far as anything prior to the 00’s.

Over the years, New York has been an epicenter for various artistic and musical movements, from punk and no wave to the current indie scene. How has the city’s alternative scene changed since your early days in it?

No young people who make good music can afford to live here anymore. There are people like me who’ve lived here long enough/become successful and can live here, but young people who live here probably are too worried scraping by to make ends meet to afford to devote any time to creating music, unless they’re nepo-babies, I suppose. A lot of younger people have moves to places like Brattleboro, VT and Asbury Park, NJ so they can afford to live while touring/writing/recording. I don’t really think there’s been a big scene here since all the DiY spaces closed about 10-15 years ago. Besides that, most music is written in Ableton or other software by one person, so it doesn’t really matter where you live or if there’s a scene. Any scene is not location-based, it’s a collective of Bandcamp/SoundCloud “sounds similar” algorithms.

My suggestion to people who want to start a band (which would be a good thing to do, writing/editing material with other people as opposed to being your own monolith): don’t move to NYC.

Today, digital platforms and social media have changed the way alternative culture develops around the world, including in New York. How do you think social media and digitalization have impacted the city’s cultural scene, especially compared to the pre-internet era you experienced at the start of your career?

I mean, I’m not that old. The internet very much existed at the start of my career. I think social media/digitalization of subcultures/art have effected everything the way everyone else does. One would think with the limitless things to listen to and the incredible ease it is to get your art on a platform for people to hear/view it, everyone still listens/likes the same bullshit. It’s more a testament to the problems with populism’s control of art over any sort of issue with the technology, As much as it would have been nice for everything available at everyone’s doorstep to create tons of incredible music, everyone listens to the same 10 songs and all of it is unchallenging, other than micro-cultures that are so niche they do not connect with each other like they once had to (see: post-disco and no wave) because you can just go and find your online community of your exact tastes. No cross-influencing and the welcoming arms of whatever music criticisim/publishing left embracing commercial music, even in the indie sphere, as opposed to taking any chances whatsoever. It’s miserable. Reap what you sow.

Mike, in the early days of Captured Tracks, you released records from bands like Dum Dum Girls, Woods, and Thee Oh Sees. How did you discover these groups, and what initially attracted you to their music that made them unique to you?

They were all friends, I was calling in favours.

Before founding Captured Tracks, you worked in record stores and as a freelance designer. In an interview, you mentioned that most successful labels are run by people with backgrounds in record stores, not necessarily by those who studied the music industry. Could you elaborate on how your experience in record stores prepared you to run Captured Tracks?

Yes, easy. When you work at a record store you listen to music 8 hours a day and talk about music 8 hours a day, largely music you would never listen to on your own accord and you have enlightening conversations with people who are passionate. I don’t see that kind of passion from people coming out of Music Industry programs. I once gave a talk at NYU for these students and they were all watching their watches waiting for it to end, save one or two people. I’ve found it more common outside the US for people in the indie music companies to have this dogmatic background, which is why the manager/lawyer-first prior to talking to labels is the norm there.

We know that Captured Tracks started with a very “DIY” approach. Was there ever a moment when you felt overwhelmed by the label’s responsibilities, and how did you manage to maintain independence while scaling the project?

Question one: No. Question Two: Hire qualified/passionate people so that the artist’s can see you are upscaling at the same pace they are becoming more popular.

You captured the essence of the independent music scene in New York in the 2010s. How would you describe the creative atmosphere of the city during that period, and how did it influence Captured Tracks’ decisions?

It was basically dead already at that point, just no one knew it yet.

During the early years of Captured Tracks, was there any failure or tough moment that you consider crucial for the label’s growth? How did you overcome it, and what did you learn from that challenge?

Yeah, I think any small business, no matter what industry, goes through stressful growth periods. For a record label, it’s hard to scale up without a back-catalog. It’s just constant re-investing everything, no spare cash/savings. That leads to financial peril. We now have a strong enough back catalog that it’s no longer a worry, I suppose the greatest feat you can achieve that actually helps you is just existing and surviving long enough to not be on the brink of total collapse at any moment.

The independent music world has changed a lot since you began. Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently with the label, or any decisions you made at the time that you now consider key to its long-term success?

No.

In your early experiences with Captured Tracks, you mentioned that some of the initial releases were more of a game than a business strategy. Over time, how did your approach to the music business change, and how do you balance the commercial with the artistic side?

I didn’t, so I had to hire people who did. If I was still in charge of that stuff, every release would be losing money. Most of what I listen to would not be possible to release in the current status of the label.

Captured Tracks has maintained a consistent visual aesthetic throughout its releases. How do you collaborate with artists and designers to create album covers that complement the music and reinforce the label’s identity? Do you do many of them yourself, or don’t you have much time?

I don’t really agree with this. Coming from an art school background, I contributed way more to the earlier stuff, along with our in-house designer Ryan McCardle.. After a while, managers/artists/et al don’t really want your input, “grass is greener on the other side” as we say here. I don’t really think we have a coherent visual aesthetic anymore, it’s more or less random.

Your relationship with Flying Nun and re-releasing classic records has been an important pillar. What do you value most about these reissues, and how do they impact your vision of preserving musical legacy through Captured Tracks?

I was/am a huge fan of Flying Nun. The scope of what we’d wanted to do… we fell short of it. A lot of it has to do with the rights Flying Nun did/did-not have with a lot of the music in their catalog. We frontlined the known entities like The Chills and The Verlaines in the hopes to get to do the more obscure stuff later, but it wound up being reissued on smaller labels. We still do tons of reissues but it’s a lot easier to work one-on-one with the artist as opposed to going through a third party, as great as Flying Nun/staff is. Just a lot of red tape. The musical legacy of Captured Tracks isn’t something I think about as much as I used to. It’s more about the artists and getting their goals achieved. Perhaps those first 5 years will be the legacy in a coherent sense, now we’re there to help those we work with more than we are concerned with the branding. I love labels, still a fan of new ones and buy all their releases, but the world no longer seems to give a shit. I remember this when Pitchfork stopped putting the label in bold on their reviews and announcing signings to labels, just “artist announces new record” like the record came out on no label, which actually is often the case now. I feel like signing to a distinguished label is no longer the dream it was in the past.

You’ve seen many bands from their early stages. Is there any story or anecdote about an artist you signed when they were still unknown that marked you or makes you remember why you do what you do?

I used to get excited about an artist we’d signed being unknown and then within a year selling out a place like Bowery Ballroom. That would be a nice close to “Chapter One” of hopefully working with someone for a while. Now, you largely sign bands who already have a successful self-release and monthly listeners or whatever, so it’s hard to pick a moment, it’s just sort of ongoing momentum.

With the rise of streaming platforms and the digitalization of music, how has Captured Tracks adapted its distribution and marketing strategies to reach a wider audience?

People react positively to good music and hate shitty music. This is the sum total of my marketing philosophy.

Looking ahead, what trends or changes in the music industry excite you, and how do you plan for Captured Tracks to adapt to them?

Oh god, nothing. There’s trends and changes to be excited about?