{ ENGLISH BELOW }

Toda leyenda tiene un inicio y la del libro “Making a Scene” se remonta a 1989, cuando la famosa editorial Faber & Faber lo publicó en una edición de 100 páginas y solamente 79 fotografías. Ahora somos testigos de una reedición de esta obra magna del hardcore de Nueva York con más de 200 imágenes y textos exclusivos que han escrito algunos de los protagonistas absolutos de esta historia musical bañada por tintes de inconformismo. Esta vuelta de tuerca a la escena de la Gran Manzana captura mejor que nunca la energía de una ciudad que no dormía nunca porque este género musical es un estilo de vida que cambió la estética y las costumbres de muchos chicos que descubrieron que el mundo no era un cuento de hadas a mediados de la década de los 80, cuando la Guerra Fría aún se respiraba en el ambiente y el Muro de Berlín era mucho más que una pared que separaba dos realidades bien distintas. Después de muchos meses de trabajo, hemos tenido la oportunidad de entrevistar a Bri Hurley, la ilustre fotógrafa que capturó con su cámara los momentos más emblemáticos de la escena hardcore de Nueva York, con todos sus iconos, las bandas legendarias y las contradicciones propias de una época que estaba llegando a su fin. Bienvenidos al centro del universo, acompañados de unas imágenes que no dejan indiferente a nadie.

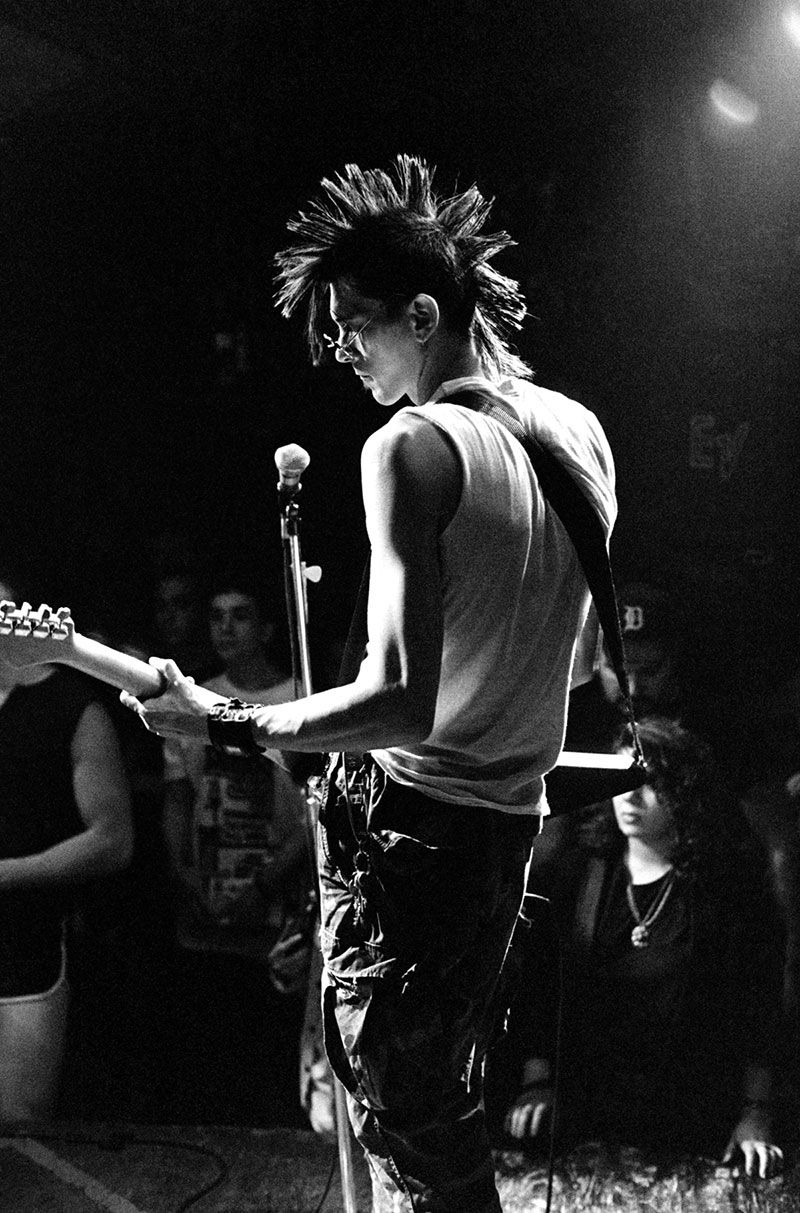

Agnostic Front. CBGBs. 22.08.88

Te propongo que empecemos esta historia por el principio. ¿Recuerdas cómo te involucraste en la escena hardcore de Nueva York?

Me trasladé a Nueva York en 1983 y me instalé en el Lower East Side, por debajo de Houston, a principios de 1984. En aquella época fui cambiando mucho de trabajo porque tuve un accidente laboral y no quería seguir en el mismo puesto porque no me gustaba. Así que empecé a fotografiar gente por la calle. Realmente quería retratar a los chavales del hardcore, pero yo misma había sido “víctima” de muchos fotógrafos intrusivos y sabía que necesitaba introducirme en ese ambiente. Ese pasaporte vino gracias a mi vecino de al lado, que era el batería de un grupo de hardcore. Cuando descubrió que yo hacía fotos, fue muy amable de dejarme pasar a uno de sus conciertos. Entonces actuaban en una sesión matinée y me dijo que me pondría en la lista de invitados, sabiendo bien que ese tipo de lista no existía en el CBGB. El tipo de la puerta, Ken Sly, pensó que estaba tratando de engañarlo cuando realmente yo no tenía ni idea de cómo funcionaban las cosas… simplemente me habían dicho que mi nombre estaría en una lista y que podría entrar gratis para fotografiar a la banda de Charley. Acabé pagando, pero logré lo que buscaba que era fotografiar a la banda. Así fue como empezó todo. Entonces estaba aprendiendo a fotografiar a grupos en directo y a gente en plena calle, me llevó mucha concentración en la parte visual conseguir el tipo de imágenes que buscaba. No utilizaba flash, así que debía prestar mucha atención a los movimientos, a la luz, a la posición y a las expresiones. Era como si la música pasara por encima mía mientras me concentraba en las imágenes.

Rest In Pieces. CBGBs

¿Crees que esa afición te cambió la vida de algún modo, igual que a tantos miembros de las bandas que retrataste?

Yo era un poco más mayor que la mayoría de chavales y venía del ambiente de las comunidades alternativas de artistas y drogas de California. Así que no fue una revelación social o cultural para mi. Siempre tuve la impresión de entender a esa gente porque estaba familiarizada con el desengaño generacional, la impresión de que la cultura convencional estaba jodida (y sigue estándolo), el querer algo distinto y el deseo de pertenecer a una comunidad para tener apoyo y cohesión. Yo venía de algo parecido y, en cierto modo, me sentía como en casa. Sin embargo, hacía bastante tiempo que vivía como una artista por mi cuenta, ya había experimentado con drogas y había visto el daño que pueden causar, pero también lo divertido que pueden ser. Asimismo, solamente tenía unos pocos buenos amigos dentro de esa escena. Puede que lo que haya cambiado mi vida fuera la publicación del libro porque me ayudó a ver que todo es posible. Aunque, lamentablemente, es algo fácil de olvidar.

¿Cuándo decidiste lanzarte a publicar un libro sobre ese movimiento musical?

Tenía un montón de fotos de bandas en plena calle. Un día hablaba con mi padre, que vivía en California, y le planteaba qué podría hacer con todas ellas. Entonces él me dijo: “¿por qué no haces un libro?” y eso fue lo que hice. Me sorprendió mucho encontrar un editor y resultó muy interesante ver el poco control y la poca opinión que el artista tiene en el mundo editorial. Es el editor el que invierte dinero y toma un riesgo. Me gustaron sus ideas y resultó fácil tratar con ellos.

Summer 1986

La primera edición apareció cuando la escena aún se vivía en presente y, en cierto modo, funcionaba como un diario de un movimiento underground… aunque la nueva edición ampliada puede considerarse un auténtico libro de historia musical.

Nunca pretendió ser un diario de esa escena. No lo hice como si se tratara de una crónica para un diario, sino que era una ventana abierta a la escena. No fui a todos los conciertos ni seguí a una banda cada semana. Simplemente iba cuando tenía tiempo, cuando un grupo que conocía estaba actuando o cuando algo me llamaba la atención. La editorial original era Faber & Faber y no asumió grandes riesgos con el libro. La editora me dijo que cada año podía dedicarse a uno o dos proyectos que quisiera, sin tener que justificarlos. La escena de Los Ángeles había aparecido en las noticias con Metzger reclutando a chavales para inculcarles el fascismo Nazi. Esos chicos causaban todo tipo de problemas a base de violencia y racismo, pero el editor no vio nada de eso en mis fotos. Así que cuando fui a hablar con ella, me preguntó por ese tema y se interesó por el papel de las mujeres y las minorías. Quería que los incluyera en el libro. Realmente, esa escena no era demasiado igualitaria entre géneros, pero tampoco era el universo misógino y racista que mostraban los medios de comunicación. Y cada concierto no acababa tampoco en disturbios. Por este motivo el libro se publicó con la idea de ofrecer un punto de vista más equilibrado y como un proyecto de interés especial por parte del editor. Tuve mucha suerte. Por el contrario, el nuevo libro es realmente una mirada histórica a esa época. Tiene un aire a medio de comunicación porque el editor no ha mantenido mis encuadres originales (que eran más artísticos) y las fotos están en una mayor escala de grises (menos contrastadas), un hecho que las hace parecer como si fueran de un periódico. Creo que tiene un estilo más crudo que encaja mejor con el tema. Todavía me sorprendo de que haya tanto interés en esa escena y también en el libro. ¡Pero es algo que me alegra mucho!

Warzone. 25.08.86

¿Qué recuerdos tienes de aquella época al ver de nuevo estas fotos?

Recuerdo todo tipo de cosas, pero nada que me resulte fácil explicar. Nunca me dio la impresión de ser un “campo de batalla” o una parte “del tercer mundo”. No fue hasta que vi un documental de uno de los artistas de aquella época que me di cuenta de cómo era todo. Entonces yo sólo aceptaba lo que había y lo que sucedía. A veces escuché historias sobre lo malo que era, así que nunca pensé que fuera malo. Sí que había lugares peligrosos, sobre todo por el tema de las drogas, los camellos y los adictos… eso sucedía en los barrios y no dentro de la escena. Pero me siento afortunada por no haberme metido en problemas, a pesar de que fui a lugares donde me avisaron de que mejor vigilara. Mi experiencia en la cultura de la droga de California me ayudaron mucho a evitar líos y entonces ya sabía que no puedes salvar a nadie. Solamente puedes darles oportunidades para que salgan de eso, pero deben ser ellos mismos quienes lo hagan. Esto me ha evitado muchos dolores de cabeza, desengaños amorosos y problemas.

¿Puedes contarnos alguna anécdota curiosa sobre tu experiencia retratando esas bandas y sus conciertos salvajes? Visto desde Europa, parece que esa escena era una gran familia…

La mayor parte de la gente me daba apoyo porque eran ellos los que habían creado esa comunidad como realmente querían. Conocía a varios chavales que venían de ambientes bastante malos y la gente de la escena los sacó de la calle, de las drogas y de esa espiral sin fin. Aunque también había veces que los chicos entraban en problemas por culpa de querer mostrar que eran fuertes o que podían ser aceptados en el grupo. Aunque lo entendía porque querían asegurarse de cómo era la persona que iba a entrar en su mundo. Personalmente, a mi nunca me retaron, pero tampoco me sentí integrada. Yo era una persona independiente y creo que eso era algo que sucedía más entre los chicos.

White Plastic. 17.08.86

¿Qué otros lugares había más allá del CBGB para disfrutar esa música en directo en Nueva York?

Había muchos otros sitios donde podían verse bandas en directo, incluso hice fotos en varios de esos lugares. Hacer fotos sin flash me obligaba a buscar ciertas condiciones para lograr imágenes decentes. Quería estar lo más cerca posible de la banda, pero nunca en medio del público porque el movimiento hacía que las fotos salieran borrosas. Las luces debían ser muy brillantes y era mejor si estaban muy cerca del escenario. Sobre todo hice fotos en el CBGB porque cumplía todos estos requisitos. También trabajé allí como camarera, así que era como mi club de referencia. Las matinée significaban que podíamos hacer fotos en la calle y también hice fotos a otros músicos, así que mientras que mi mundo “punk / hardcore” era bastante pequeño, mi mundo general era más grande. En las fotos del libro pueden verse otros lugares como Tompkins Sq. Park e Irving Place.

¿Crees que la escena hardcore de Nueva York se dividía en pequeños grupos o tribus? ¿Qué crees que los hacía distintos en aquella época?

Realmente había otros grupos o tribus, puesto que existían otros tipos de música con sus respectivos seguidores y artistas relacionados. Muchos de ellos estaban separados por el tipo de arte que hacían o donde vivían. La gente era distinta dependiendo de los clubes a los que iban. Había distintas tribus dentro del hardcore, pero la escena tampoco era tan grande. La gente se conocía perfectamente. Algunos iban a ver a bandas que no eran su artista principal, pero había una aceptación generalizada de los grupos y subgrupos. El CBGB también tenía un público muy variado por las noches y dependiendo de la banda que actuaba. No sé si eso aún existe hoy en día porque no he vivido en Nueva York desde 1989 y estar allí de visita no me da la oportunidad de apreciar estas cosas.

Underdog, Irving Place. 31.10.87

Por curiosidad, ¿tuviste la oportunidad de viajar por los Estados Unidos y apreciar cómo eran las otras escenas de punk y hardcore que existían al mismo tiempo?

Nunca viajé con este propósito. Cuando salí de Nueva York sí que fui a ver algunos conciertos a San Francisco, pero no me sentía conectada. Podía ser que yo hubiera cambiado o que ellos fueran distintos, pero nunca me sentí cómoda. También puede ser que no me diera suficiente tiempo para encontrar mi sitio allí. No puedo decirte por qué Nueva York era tan especial, sólo puedo decirte que era especial para mi. Estuve allí en el momento correcto y me fui en el momento adecuado. No creo que haya lugares más especiales que otros, sino que es la relación entre el sitio y el momento. He tenido al enorme suerte de estar en ciertos sitios en el momento perfecto… como en Nueva York a mediados de los años 80, Praga a mediados de los 90, Gates a principios de los 70. Me gustaban los músicos por su energía, su mensaje, su sinceridad y el corazón que ponían en todo lo que hacían.

¿Por qué el libro se ha reeditado en un formato más pequeño si ahora tiene muchas más fotografías?

Las decisiones sobre el formato y las fotos nuevas vinieron por parte de Chris Daily, el editor, igual que las elecciones en la calidad de impresión y el encuadre de las imágenes. Yo tenía derecho a veto y podía aportar mi punto de vista. Me encantó saber que habría más material, pero resulta que en aquellos días me estaba mudando y trataba de vender mi casa. Mi vida era un caos y mi participación en el diseño no fue tan grande como me habría gustado. Estoy convencida de que a Chris le encantaría contarte cosas sobre sus decisiones. Lo mejor es que aparecen más fotos organizadas por categorías, como calles, bandas visitantes, bandas locales, etc. También puedes leer textos escritos por otras personas, cosa que me parece muy interesante.

Nausea, Thompson Park

Aunque eres muy conocida por tus fotos relacionadas con la música, ¿te has planteado capturar otro tipo de imágenes o de personas? ¿Qué otras aficiones tienes cuando no estás haciendo fotos?

Se me conoce por mis fotos en un ambiente muy pequeño y específico. E incluso entre esa gente, mis imágenes son más famosas que mi nombre. He hecho muchos otros tipos de fotos, desde retratos hasta desnudos, pasando por temas de viajes. No se trata de mi trabajo principal porque no quería fotografiar bodas o retratos para pagar mi alquiler.

Otra de tus facetas profesionales ha sido la creación de portadas de álbumes. ¿Podrías contarnos cuáles son las que más te gustan y cómo fe la relación con las bandas?

Yo no fui la persona que diseñó las portadas de los álbumes, sino que utilizaron mis fotos para ese fin. Yo entregaba las imágenes a las bandas y ellos eran libres para utilizarlas como quisieran. Así fue como acabaron apareciendo en pósteres, portadas de discos e incluso en camisetas. Mi relación con las bandas era lo suficientemente buena para que no me echaran del escenario. Como en toda relación, algunas eran más cercanas que otras… algunas eran como compañeras de trabajo, algunas eran amigas y a otras no las conocía tan bien. El único grupo con el que recuerdo que hubo cierta hostilidad era de fuera de la ciudad. De eso ya hace mucho tiempo y las bandas se alegraban de tener sus fotos. Algunas veces me invitaban a hacerles más fotos y así fue como me involucré en todo esto.

¿Crees que en el futuro habrá un segundo volumen de tu libro con fotos inéditas que se han quedado en el tintero?

Lo dudo mucho… aunque entonces no pensaba que algún día se hiciera una nueva edición. Nunca sabes lo que te deparará el futuro.

Trip Six. 10.05.87

Absolution, Tompson Park

Spring 1986

Nausea. CBGBs. 26.10.86

Matinee. 16.03.86

(ENGLISH)

BRI HURLEY.

“MAKING A SCENE”: HISTORY OF NEW YORK HARDCORE

Every legend has a beginning, and the one of the book “Making a Scene” goes back to 1989, when the well-known publisher Faber & Faber released it in a 100-page edition with only 79 photographs. Now we witness a re-edition of this New York hardcore masterpiece with more than 200 images and exclusive texts with hints of non-conformism written by some of the absolute protagonists of this musical history. This further pressure to the Big Apple scene captures better than ever the energy of a city that never sleeps, because this music genre was a lifestyle that changed the aesthetic and habits of many guys who found out that the world wasn’t a fairy tale in the mid 80s, when the Cold War was still present and the Berlin Wall was much more than a wall that separated two very different realities. After many months of work, we had the chance to interview Bri Hurley, the distinguished photographer who captured the most emblematic moments of the hardcore scene in New York: all its icons, the legendary bands and the contradictions typical from a period that was coming to an end. Welcome to the center of the universe, accompanied by some images that won’t leave you indifferent.

Let’s start from the beginning: how did you get involved in the NYHC? When did you discover that scene? Do you think it changed your life in some way?

I moved to NYC in 1983 and then to the Lower East Side, below Houston in the beginning of 1984. I was changing jobs as I’d had an accident at work and no longer wanted to be in that unpleasant atmosphere. I began to photograph people on the street. I wanted to photograph the hardcore kids but I’d been the subject of so many intrusive camera wielding people, so I knew that I needed a way into that world. That way in came in the form of my next door neighbour, who happened to be a drummer in a hardcore band. When he found out I took pictures, he was quite keen on getting me to a show.

They were playing a matinee. So he told me that he’d put me on the guest list, knowing full well that no such list exists at CBGB. The door man, Ken Sly, thought I was trying to pull one over on him, when I truly didn’t have a clue. I’d been told I’d be on some list and could get in free, so I could shoot Charley’s band. I ended up paying. But then, I also got what I wanted, an excuse to shoot to my heart’s content. That’s how it started. Back then I was just learning how to shoot live bands and on the street. It took a lot of concentration on the visuals to get the shots I wanted. I didn’t use a flash, so I really had to be aware of the movement, light, position and the expression. The music just sort of washed over me as I focused on the visuals.

When did you decide that you wanted to publish a book about that music scene?

I had heaps of photographs of bands and on the street. I was talking with my father (in California) and wondering what in the world I was going to do with them all. He said, “why don’t you do a book?” So I did. I was actually surprised to find a publisher. It was interesting to see just how little control and input the artist has in a situation like publishing. It’s the publisher that is spending the money and taking the risk. I was really happy that I liked their ideas and that they were easy to deal with.

The first edition came out when the scene was still happening, so it was more like a diary about that underground movement although the new edition can be seen as an historical book. Do you think the editor was taking a big challenge back then?

It was never really a diary of the scene. I didn’t chronicle the scene as diligently as one would expect of a diary. It was more like a window being opened from part way inside. I didn’t go to every show or follow one band all the time. I went when I had time, when a band I knew was playing or when a show caught my eye. The original publishing company (Faber and Faber) did take a big risk with this book. The editor said she had one or two projects each year where she could do what she wanted... within reason. And she had some recent media to ‘hang’ it on as there had been some pretty poor publicity.

The scene in LA had been in the news with Metzger recruiting boys that he was indoctrinating into Nazi fascism. These kids were causing all sorts of trouble with violence and racism. The editor wasn’t seeing that in my photos. So when I went to meet her, she asked about it and she was interested in the role of women and minorities. She wanted me to include them. The scene wasn’t really a level playing field (so to speak) between the genders, but it wasn’t the misogynist, racist hotbed that the media was portraying either. Nor was every show a riot. So the book got published as a way of showing a more balanced view and as a special interest project of the editor who happened to actually open and read the package I sent. I was very lucky. The new book is definitely a historical look at that time. It has a more media feel in that the publisher didn’t keep my original (more artistic) crops and the photos are on a more grey scale (less contrasty), which makes them look more like news paper photos. It’s got a rougher feel to it. That fits the subject. I am still surprised that there is so much interest in that time. And very surprised there is so much interest in the book. Of course, I’m happy for it too!

What do you remember about those days when you see your photos?

I remember all sorts of things when I see the photos, but nothing that’s easy to pin down. It didn’t occur to me that it looked like a war zone or even like a third world country. It wasn’t until I saw an artist documentary from the time that I realised how it looked. At the time, I just accepted what was there, what was happening. I had heard some stories about how bad it ‘used to be’, so I didn’t think it was bad.There were places that were dangerous. Usually it had to do with drugs, dealers and addicts, more about the neighborhood than the scene. Again, I was fortunate and didn’t find myself in any trouble, even though I went to some places that people warned me about. My background in the Californian drug culture really helped with that and I also already knew (from experience) that you can’t save anyone. You can only give them opportunities to pull themselves out. They are the ones that have to do it themselves. This saved me more headaches, heartbreaks, and trouble than I can begin to tell you.

Can you explain us any cool anecdote about being there taking pictures? From Europe, we saw that scene like a big family.

So many of the people were very supportive. They created the community that they wanted. I know quite a few kids who were coming from bad situations and the people in the scene really saved them from the streets, from drugs, from that downward road. Although there were also times when new kids were challenged. A little ‘are you hard enough?’ or can you pass my test before I accept you… I understood that too. Sometimes they wanted to be sure of the person they were going to give their support and energy and loyalty. I personally, didn’t really experience being challenged. But then, I also never felt like I was really on the inside. I was pretty self contained and independent. I also think it was more among the boys.

Do you remember other places other than the CBGB where all these musicians met during that time?

There were definitely other places. I saw some bands in other venues and even shot at a few of them. Shooting without a flash made certain conditions optimal for decent photos. I wanted to be close to the band, but not in a surging crowd (as the movement would blur the photos). The lights needed to be fairly bright and best if they were close to the stage. I mostly shot at CBGB. It fit all these criteria. I was also working there as a bartender, so it was my home club. The matinee’s meant daylight shooting on the street as well. I did know and shoot other musicians, so while my personal ‘punk/hardcore’ world was pretty small, my world in general was bigger. Included in the photos are shots from other locations. Tompkins Sq. Park, and Irving Place.

Do you think there were smaller groups / tribes of people inside the NYHC? What made them different from each other?

There were definitely other groups, or tribes. There were other kinds of music with their followers and there were artists, some of whom were separated by the type of art they did or where they lived. The people were also different depending on what clubs they went to. There were quite different tribes within the hardcore scene. But the scene was not that big, so people knew each other. They went out to bands that weren’t their main group and there was a general acceptance of the divers groups or subgroups. CBGB also had a completely different crowd at night and then different again depending on the bands playing. I have no idea if it exists now. I have not lived in NYC since 1989 and visiting doesn’t really give me the chance to really see this.

In those days there were many cities and many music scenes. Did you travel across the US? Did you see any differences between the scenes in NYC, Washington, Seattle and LA? Why do you think NYC was so special?

I didn’t travel in this regard. When I moved from New York City, I went to a few shows near San Francisco, but I didn’t feel a connection. Could be that I’d changed, or they were different, I just didn’t feel it. Could also be that I didn’t give it enough time to find my place there. I can’t really say why New York was so special. I can only say that it was special to me. I was there at the right time and I left at the right time. I fully believe that it’s never just a place that is special but it must be a place at a particular time. I’ve been really fortunate to be in certain places at the perfect time, like NYC in the early-mid ’80s, Prague in the mid ’90s and the Gates in the early ’70s.

Why the book has been reissued in a smaller format, when it has more photos? Which new stuff can we find in it?

The choices about format and added photos came from Chris Daily, the publisher, as did the choices in print quality and image cropping. I had veto power and input. I was happy that there would be more photos. But I was moving and trying to sell my house at the time. My life was in chaos and my participation in the design aspect was not as great as I would have liked. I’m sure Chris would be happy to talk to you about his decisions. There are more photos from each type or category and they have been organized into sections like, on the streets, visiting bands, local bands…. You can also find things written by other people, which I find very interesting.

You are well-known for your music photos, but do you take other kinds of pictures? Is photography a main job for you? What do you enjoy doing when you are not carrying your camera?

I am known for my photos amongst a very small, very specific segment of people. And even among those people, my images are known better than my name. I have taken many other types of photos. They run the gamut from portraits to nudes to travel images. It is not my main job. I didn’t want to shoot weddings and headshots to pay the rent.

You have created some album covers. Which ones are you most proud of and how was your relationship with the bands?

I actually didn’t create any album covers. My artwork was used on a number of album covers, but I cannot claim design or creation. I would give the bands photos I’d made, and they were free to use them how they wanted. So they appeared on posters, albums and even tee shirts. My relationship with the bands was good enough that they didn’t kick me off the stage. Like any relationships, some were closer than others. Some of them were my co-workers, some of them were my friends, some I didn’t know very well. The only band that I remember any hostility from was from out of town. That was a long time ago, and the bands were happy to get photos. Sometimes, they would invite me to come take pictures. That is how I first got involved with all this.

Do you think there will be a second volume of your book with never seen before images in the future? Did you take pictures of other music scenes?

I doubt it. But then I didn’t think there would ever be a reprint of the original. You never know what the future holds.

Buy the book “Making A Scene” here: Butter Goose Press