{english below} Laura Wilson es una representante por derecho propio de la generación de fotógrafos que se dedicaron a documentar la vida en Usa y que fueron en gran medida los que sentaron las bases de lo que conocemos como fotografía documental. En sus fotografías encontramos ese destello atemporal que hizo a mucho de nosotros enamorarnos de este medio, la curiosidad por el otro, el enigma que se nos presenta al observar un retrato. Sus trabajo destilan una forma atemporal de entender la fotografía documental que sigue estando muy vigente como una forma de acercarnos al enigma que es el mundo.

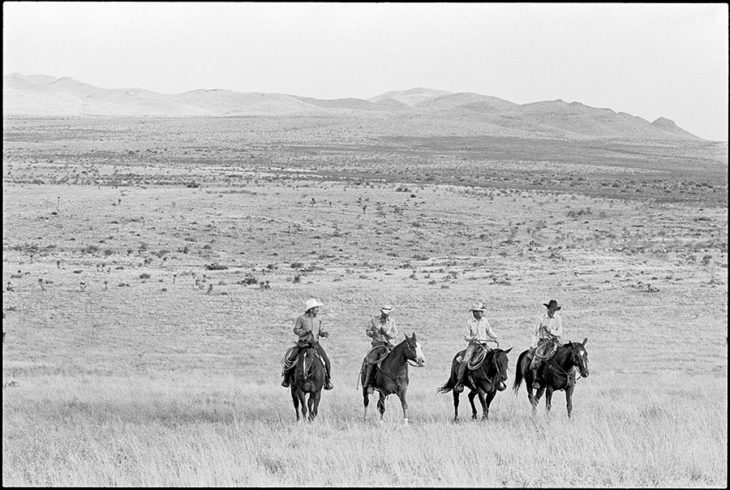

Laura Wilson. New Mexico, 2013

¿Qué te atrajo de la fotografía en primer lugar?

Cuando era muy joven, las fotografías me absorbían por completo. Me di cuenta de que una fotografía podía responder a preguntas que ni siquiera sabía que tenía ¿Así era mi madre antes de que yo naciera? ¿Este es el aspecto de mi padre y sus hermanos de pie sobre las rocas con vistas al océano en Maine? Una fotografía guarda recuerdos. Puede disolver el tiempo. Puede mantener intactas la familia, el lugar y las experiencias.

In the American West, de Avedon, se ha convertido en un libro imprescindible de la fotografía del siglo XX. A Robert Frank se le acusó de ser un forastero, alguien que no entiende la idiosincrasia del lugar ¿Pero puede ser que venir de otro lugar le sirve para tener una visión más lúcida?

Sin duda. El forastero suele ver las cosas con más claridad. Sus observaciones se agudizan por lo desconocido y ve lo que diferencia a un tema. Así fue en el caso de Frank, que vino de Suiza y vio América de forma elemental y sorprendente. Richard Avedon, como Frank, era un forastero. Richard Avedon, al igual que Frank, era un forastero, que vino de Nueva York al Oeste americano y, como forastero, tenía una visión muy clara. Contradijo el Oeste de John Wayne y John Ford para ofrecer una visión más realista y mordaz de esta diversa región.

Hutterite Girl in Wheatfield, 1991

La idea de la frontera es una constante en la cultura estadounidense (me viene a la mente Huckleberry Finn). ¿Qué te parece interesante de estos territorios?

Siempre me ha gustado esta cita de Archibald MacLeish: “Al este estaban los Reyes muertos y los sepulcros recordados: Al oeste estaba la hierba” y todavía me conmueve su significado. La frontera americana representa la libertad. Esto es cierto incluso en el siglo XXI y a pesar del caos causado por los cárteles de la droga a lo largo de la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México. El camino abierto del Oeste americano es un símbolo de independencia y expresión individual. El extenso paisaje de amplias praderas y grandes cielos, la falta de asentamientos y la mentalidad sin tonterías, todo ello conduce a un espíritu independiente que todavía nos atrae al Oeste.

Hutterite Girls During Hay Making Season, 1991

En una entrevista dijo que lo más difícil del retrato es romper con la imagen que tenemos de nosotros mismos. ¿Cómo planifica una sesión de retrato?

Para que una sesión de retrato tenga éxito, necesito saber lo suficiente sobre el sujeto para poder interactuar con él, para poder aportar un punto de vista a la sesión. Para mí, sin embargo, hay una delgada línea entre estar preparado para un retrato y estar demasiado impresionado por los logros de mi sujeto. Si sé demasiado sobre alguien, eso puede interferir en la forma en que yo, como fotógrafa, respondo a ellos. Es mejor ver claramente su rostro y su forma, en lugar de estar agobiado por demasiados conocimientos. Las personas son complicadas y los mejores retratos requieren enfoque, respuestas rápidas y agilidad emocional.

Tus fotografías reflejan en cierta medida mundos cerrados, tanto geográfica como socialmente ¿qué historias buscas en estos espacios?

Sí, en casi todos los casos mis fotografías reflejan mundos cerrados y apartados. Estas comunidades pueden estar aisladas geográficamente, o socialmente, o por sus logros. Tal vez hayan sido vistas con menos frecuencia o examinadas de forma poco significativa. Esto me permite decir algo sobre ellos que otro fotógrafo no ha tenido la oportunidad de hacer.

Hutterite Boy on Appaloosa, 1993

También vemos estos mundos cerrados en tus fotolibros, donde hablas de las raíces y de tener un lugar en el mundo. ¿Cree que todos sus libros tienen en cierta medida un hilo conductor?

Sí, todos mis libros son un intento de abrir el telón, de permitir que uno vea vidas diferentes a la suya. No se trata de juzgar, sino de responder a la verdad de la persona que está delante de la cámara. El hilo conductor de todos mis sujetos es su sentido del lugar. Por ejemplo, en mi proyecto actual de fotografiar escritores, busco sus raíces, sus influencias, lo que responden en sus entornos. En el pasado, he documentado a personas alejadas del mainstream estadounidense y, del mismo modo, estos escritores de alto nivel se han alejado en cierta medida de la sociedad principal. Todos ellos comparten la fuerza de la soledad y la independencia con mis anteriores temas.

Hand and Spur, 1992

Ese día fue una exposición importante, en la que repasó 35 años de tu carrera. ¿Fue un punto de inflexión en el autoconocimiento de su obra?

Ese día fue un punto de inflexión para mí porque me impulsó a trabajar más y con más intensidad y conciencia. Ver las 84 imágenes, impresionantes por su tamaño y alcance en la pared, me hizo estar ansiosa por volver a trabajar y seguir profundizando en mi fotografía.

Greg Wakabayshi fue el editor del libro de la exposición (In That day), un libro donde la narrativa juega un papel muy importante. ¿Es importante el texto a la hora de dar claridad a una fotografía?

Las mejores fotografías, pensemos en las de Henri Cartier Bresson o Robert Frank, no necesitan texto porque la combinación de geometría y contenido es tan fuerte y tan clara, que el mensaje del fotógrafo llega directamente al corazón. En un libro, se incluyen algunas imágenes que no podrían sostenerse por sí solas, pero que, al añadirse al conjunto de la obra, aportan contexto y significado. En este caso, el texto es muy importante para ampliar el significado o los matices de un tema concreto.

Cowboys Galloping, 1996

La generación de Stieglitz toma como referencia las nubes y las olas. Para la generación de Evans la referencia eran otros y las imágenes de películas o de publicidad. ¿En qué momento cree que se encuentra la fotografía americana?

Me complace pensar que la fotografía estadounidense está volviendo a la tradición de la fotografía documental. Me he impacientado los últimos 30 años con la fotografía conceptual porque no creo que sea tan convincente como la pintura o la escritura. Pero es terriblemente difícil, cuando respondes a la realidad que tienes delante, superar el impacto de una buena fotografía. Creo que la gran fuerza de la fotografía es cuando está impulsada por la realidad.

Creo que muchas de tus fotos trabajan para la posteridad, buscan dejar constancia del paso por el mundo. ¿Cree que esta búsqueda de la posteridad es una de las cualidades del retrato?

Absolutamente, ¿cómo podríamos saber el aspecto de Abraham Lincoln o de Pablo Picasso si no tuviéramos la cámara? Es un invento increíble, la invención de la fotografía fue realmente una revolución.

Favorite Roping Horse, Corazon, 1992

En los últimos años ha habido un gran interés por el formato del fotolibro, que se ha convertido en un género fotográfico en sí mismo. ¿Qué aporta el formato libro a la fotografía?

El formato libro permite al fotógrafo una visión ampliada de un tema y secuenciar las imágenes de forma que aporten fuerza y claridad a un tema. Un buen libro es una exploración sostenida y profunda de un tema. En un libro, el fotógrafo puede reforzar los temas que impulsan su creación. Dicho esto, todos los libros necesitan una edición sólida y el fotógrafo no siempre es la persona más adecuada para hacerlo. Todos tenemos nuestras favoritas, la toma que esperamos, la imagen que tardó años en ejecutarse, pero eso no siempre las convierte en la mejor fotografía. Los fotolibros deben ser editados rigurosamente para que el resultado final tenga la mayor fuerza posible.

Dentro de la amplia tradición de la fotografía estadounidense, ¿dónde te gustaría insertarse?

Me gustaría que mi trabajo se insertara entre los fotógrafos documentales más fuertes. No quiero que se me considere únicamente como una mujer fotógrafa o una fotógrafa del suroeste. Los temas del aislamiento, la familia, las dificultades y el sentido del lugar, son temas universales.

Cowboys on Horseback, Y-6 Ranch, 1992

¿Cómo te ayudó a desarrollar sus ideas sobre la fotografía trabajar con Avedon durante tantos años?

Avedon fue muy influyente. Vi lo serio que se tomaba a sí mismo y a su talento. Su energía, su curiosidad y su capacidad para trabajar sin limitaciones fueron atributos importantes en su carrera. No se preocupaba por el diafragma o las velocidades de obturación, aunque sabía cómo hacer, e imprimir, una bella fotografía. Para Avedon, al hacer un retrato, se trataba de revelar algo dentro de la persona, hacer una imagen que pudiera “sostener la pared”. Al observarlo, un fotógrafo en la cima de su carrera, vi claramente lo que hacía una fotografía fuerte.

¿Qué es lo que le inspira ahora la fotografía?

Exactamente lo mismo que me inspiraba cuando tenía seis años: el misterio absoluto, la emoción y el entusiasmo de una fotografía. Y ahora me siento muy afortunada de tener la habilidad y la capacidad técnica para realizar las fotografías que tanto deseo.

www.laurawilsonphotography.com

Watt Matthews, Stone Ranch, 1986

Jim Harrison, Montana, 2012

J.M. Coetzee, Vienna, 2019

Seamus Heaney, Dublin, 2011

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mexico City, 2012

Avedon Photographing Johnson Sisters, 1983

Avedon Balancing on Pole, 1982

Avedon and Ronald Fischer, 1981

Red Headed Sisters, 1995

English:

LAURA WILSON. REALITY-DRIVEN PHOTOGRAPHY

Laura Wilson is a representative in her own right of the generation of photographers who dedicated themselves to documenting life in the USA and who were largely the ones who laid the foundations of what we know as documentary photography. In her photographs we find that timeless sparkle that made many of us fall in love with this medium, the curiosity for the other, the enigma that presents itself to us when observing a portrait. Her work exudes a timeless way of understanding documentary photography that is still very much alive as a way of approaching the enigma that is the world.

What attracted you to photography in the first place?

As a very young child, I was completely absorbed by photographs. I realized a photograph could answer questions I didn’t even know I had. This is what my mother looked like before I was born? This is what my father and his brothers looked like standing on rocks overlooking the ocean in Maine? A photograph holds memories. It can dissolve time. It can keep family and place and experiences intact.

Avedon’s In The American West has become a must-have book of 20th century photography. Robert Frank was accused of being an outsider, someone who doesn’t understand the idiosyncrasies of the place. Could it be that coming from somewhere else serves to give you a more lucid vision?

Absolutely. The outsider can often see things more clearly. His observations are sharpened by the unfamiliar and he sees what sets a subject apart. This was true of Frank, who came from Switzerland and saw America in elemental and surprising ways. Richard Avedon, like Frank, was an outsider. Avedon came from New York City to the American West and, as an outsider, he had a clarity of vision. He saw the American West in a less romantic way. He contradicted the West of John Wayne and John Ford to deliver a more realistic and biting view of this diverse region.

The idea of the frontier is a constant in American culture (Huckleberry Finn comes to mind). What do you think is interesting about these territories?

I’ve always loved this quote by Archibald MacLeish, “East were the dead Kings and remembered sepulchers: West was the grass” and am still moved by its significance. The American frontier represents freedom. This is true even in the twenty-first century and in spite of the chaos caused by drug cartels along the U.S. Mexico Border. The open road of the American West is a symbol of independence and individual expression. The expansive landscape of wide, open prairies and big skies, the lack of settlements, and nonsense mindset, all lead to an independent spirit that still draws us to the West.

In an interview you said that the most difficult thing about portraiture is to break with the image we have of ourselves. How do you plan a portrait session?

For a successful portrait session, I need to know enough about my subject to be able to interact with them, to be able to bring a point of view to the session. For me, however, there is a fine line between being prepared for a portrait and being overly awed by my subject’s accomplishments. If I know too much about someone, that can get in the way of how I, as a photographer, respond to them. It is best to see clearly their face and their form, rather than being burdened by too much knowledge. People are complicated and the best portraits require focus, quick responses, and emotional agility.

Your photographs to some extent reflect closed worlds, both geographically and socially, what stories do you look for in these spaces?

Yes, in almost all cases my photographs reflect closed, secluded worlds. These communities can be isolated geographically, or socially, or by their accomplishments. Perhaps they have been seen less often or examined in less meaningful ways. This allows me to say something about them that another photographer hasn’t had the opportunity to do.

We also see these closed worlds in your photobooks, where you talk about roots and having a place in the world. Do you think that all your books to some extent have a common thread?

Yes, all my books are an attempt to part the curtain, to allow one to see lives different from one’s own. This is not meant to judge, but to respond to the truth of the person in front of the camera. The common thread for all of my subjects is their sense of place. For instance, in my current project photographing writers, I am looking to their roots, their influences, what they respond to in their environments. In the past, I have documented people removed from mainstream America and, similarly, these highly accomplished writers have removed themselves to a certain extent from mainstream society. They all share the strength of solitude and independence with previous subjects of mine.

That Day was an important exhibition, where you reviewed 35 years of your career. Was it a turning point in the self-knowledge of your work?

That Day was a turning point for me because it spurred me on to work harder and with more intensity and awareness. To see the 84 images, impressive in their size and range on the wall, made me anxious to get back to work and to continue to dive deeper into my photography.

Greg Wakabayshi was the editor of the book of the exhibition (In That day), a book where narrative plays a very important role. Is text important when it comes to giving clarity to a photograph?

The greatest photographs, think of those by Henri Cartier Bresson or Robert Frank, do not need text because the combination of geometry and content is so strong and so clear, that the photographer’s message goes straight to your heart. In a book, you include some images that could not stand on their own, but when added to the body of work, they provide context and meaning. In this case, text is very important in amplifying the significant nuances of a particular subject.

Stieglitz’s generation takes clouds and waves as a reference. For Evans’ generation the reference was others and film or advertising images. Where do you think American photography is now?

I am pleased to think that American photography is returning to the tradition of documentary photography. I have been impatient the last 30 years with conceptual photography because I don’t think it is as compelling as painting or writing. But it is awfully hard when you are responding to the reality in front of you to beat the impact of a good photograph. I believe that photography’s great strength is when it´s propelled by reality.

I think that many of your photos work for posterity, they seek to leave a record of the passage through the world. Do you think this search for posterity is one of the qualities of portraiture?

Absolutely, how else would we know what Abraham Lincoln or Pablo Picasso looked like if we didn’t have the camera? It is an incredible invention- the invention of photography really was a revolution. A longing for posterity is at the heart of portraiture, and of all photography really.

In recent years there has been a great interest in the photobook format, becoming a photographic genre in itself. What does the book format bring to photography?

The book form allows a photographer an extended view of a subject and to sequence the images in a way that brings strength and clarity to a subject. A good book is a sustained, in depth exploration of a subject. In a book, a photographer can reinforce the themes driving its creation. That said, all books need to be strongly edited and the photographer is not always the best person to do that. We all have our favorites, the shot we waited on, the image that took ages to execute, but that does not always make them the best photograph. Photobooks need to be stringently edited so that the final result has as much power as possible.

Within the broad tradition of American photography, where would you like to be inserted?

I would hope that my work will be inserted among the strongest documentary photographers. I don’t want to be thought of solely as a woman photographer or a photographer of the Southwest. The themes of isolation, family, hardship, and sense of place, are universal subjects.

How did working with Avedon for so many years help you develop your ideas about photography?

Avedon was very influential. I saw how seriously he took himself and his talent. His energy, curiosity, and ability to work without constraints were important attributes on his career. He didn’t care about F-stops or shutter speeds, although he knew how to take, and print, a beautiful photograph. For Avedon, in doing a portrait, it was about revealing something within the person, making an image that could “hold the wall.” In watching him, a photographer at the top of his game, I saw clearly what made a strong photograph.

What is it about photography that inspires you now?

The exact same thing that inspired me when I was six years old- the absolute mystery, excitement, and thrill of a photograph. And I feel so lucky now to have the skill and technical ability to accomplish the photographs I long to take.