{english below} Tras siete ediciones, “Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes From the DC Punk Underground (79–85)” se ha convertido en parte del lenguaje visual del punk rock Americano universal. Encabezado por Cynthia Connolly y uniendo fuerzas con Leslie Clague y Sharon Cheslow, este libro constituye un viaje que va más allá de los tiempos jóvenes de la escena punk de Washington. Mientras que las imagines y el texto describen a la perfección el espíritu de una de las escenas del punk más amplias del mundo, el sentimiento más puro es lo que ha hecho de “Banned in DC” todo un símbolo.

Charlando con Connolly, mencioné mi primer contacto con el libro a principios de los 90 y cómo DC ensalzó la escena a límites desmesurados. Tras décadas movido de su impresión original y en un momento en el que la existencia del papel se encuentra en boga, “Banned in DC”, actúa como contrapunto para todos aquellos que desean recorrer caminos alternativos. Como cualquier pieza de arte, el libro conecta a individuos que comparten su amor por la colección y la escena que documenta, creando una vibra y un sonido que elimina todo el ruido y el estancamiento generado en la cultura pop.

Si eres de los que ama “Banned in DC”, es una señal de que la buena documentación y el mimo son postulados de la inspiración. Teniendo trabajos como “Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes From the DC Punk Underground (79–85)” en papel, más que un homenaje o un símbolo de nostalgia, nos encontramos ante una afirmación de la posibilidad de lo que puede ser conseguido de manera independiente, cuando las cosas tienen que pasar y cómo ese trabajo puede seguir moviendo al punk en la dirección adecuada.

Comentas en el libro que buscas una alternativa al rol de macho alfa que predomina en la escena del rock ‘n’ roll que viviste como adolescente. ¿Ocurre lo mismo en la escena punk emergente de LA?

Lo percibí inmediatamente, porque había muchas chicas en los grupos. Evidentemente, había más tíos involucrados que mujeres en aquel momento, pero porque mi perspectiva se basa en California. Creo que estábamos adelantados. Había mujeres directoras y había muchas mujeres haciendo cosas muy interesantes en otras industrias y altos puestos en Los Ángeles. Así que, supongo que lo concebí de un modo tan complejo como sencillo podía ser en LA.

En D.C, había más o menos el mismo porcentaje de hombres y mujeres, pero hubo una “excepción” sobre la que hablo en el libro. Ocurrió en Junio de 1981. Había un show en el 9:30 Club con bandas punks locales como Minor Threat, Government Issue y Artificial Peace. Muchos conciertos anteriores a ese se habían celebrabado en locales más pequeños que no estaban dirigidos a conciertos.

En ese concierto, había también chavales de fuera de la ciudad: Nueva York, Boston…Bailaban de una manera más violenta, de lo más parecido a los estilos más agresivos del slam dancing. A partir de entonces, empecé a perder el interés en la música y en todo lo que ocurría alrededor del escenario y me enfoqué más en la gente que había por ahí.

Así que podías encontrarme fuera hablando con la gente con mucha frecuencia. Muchas chicas hacían eso mientras los chicos estaban dentro bailando a golpes. Y eso ocurrió por todo US al mismo tiempo y en las diferentes escenas punk.

Como resultado, tome fotos en 1981 con una cámara presada (la mía me la robaron en LA) porque no había mucha gente echando fotos. Paré cuando otras personas empezaron a hacer lo mismo en 1982. Además también comencé con los estudios de arte.

Contribuí a la escena estando ahí, ayudando a Dischor con su correo o prestándoles algo de dinero para alguno de sus lanzamientos. Y, en 1983, dibujé la oveja negra de la portada de “Out of Step” EP.

dibujo original de la oveja negra del “Out of Step”

Crees que la escena punk fue una extensión de la escena artística que se daba lugar en Los Ángeles en aquel tiempo, algo así como un nuevo medio de exploración?

Bueno, podía verse una mezcla, por el hecho de que la industria del entretenimiento se encontraba en Los Ángeles, el campo creativo más amplio (ya que incluye el diseño de decorados de películas, de vestuario, actuación y música, y luego, el arte contemporáneo). Las líneas divisorias eran confusas y por ese motivo en LA, había mucha mezcla. También habría que añadir una nueva ola de gente metida en el diseño de ropa y la moda, que obviamente, también estaba relacionada con la música alternativa de LA y que ya abría sus propias tiendas en lo que se convirtió en “The” Melrose Avenue. Las primera tiendas más trendy eran las punk/new wave, ya que tenían ropa que nadie antes había diseñado.

Washington DC no es una ciudad para nada creativa. Es una ciudad política y si en algo no existe la creatividad es en la política…y más en el D.C. que era bastante conservador. Ronal Reagan acababa de ser elegido y eso era lo que marcaba la diferencia.

O sea que el DC fuese más conservador hizo de la escena del punk algo más creativo…o reactivo?

Era mas reactivo que el lugar en el que se encontraba emplazada. Hay algo que me resulta irresistible de Washington y que aún lo es: y es que constituye un verdadero reto hacer que suceda algo en un lugar donde no se percibe ni medio germen creativo. Es lo que siempre me ha parecido divertido de la escena del punk también: sigue siendo emocionante cuando te cruzabas con alguien que también disfruta de ello ya que solemos ser personas bastante dispares entre nosotras.

Con una forma de arte creada en un ambiente tan opresivo y conservativo, hay gente que podría mirar atrás y pensar en la idea de los “Straight Edge” como ideal conservador.

Conocí a Ian justo después de que escribiera esa canción y antes de que fuese lanzada. Fue una reacción a su propia experiencia de madurez, como lo eran todas sus canciones. Ese tema puede ser considerado como conservadora, pero de algún modo, era radical para aquel momento, y más aún proviniendo de los 70 y los 60 donde amigos míos habían crecido fumando porros con sus padres.

“Straight Edge”, proponía ese set de reglas que se suponía que debía ser establecido de por tus padres. Pero en ese momento, las hijos discutían las normas de los padres que nunca ponían normas. Cualquiera que haya crecido en esa época lo sabe. Al final, Ian veía el emborracharse una pérdida de tiempo. Todos sabemos que los jóvenes desperdician su juventud, pero Ian era demasiado joven para hacer una afirmación tan rotunda. Era una persona apasionada que reaccionó ante lo que le rodeaba.

Había otro montón de gente que era mayor que nosotros por aquel momento, que estaban más en el rollo de la new wave, el punk temprano y la heroína. Muchos de ellos murieron o cogieron alguna enfermedad por compartir agujas. Cuando piensas sobre ello, el movimiento “Straight Edge” caminaba en paralelo a la campaña de Nancy Reagan “Just Say No” pero no creo que se influyeran entre ambos.

Cuando comentas que contabais con la casa de Ian como una especie de salón al servicio de la escena, me hace pensar en la importancia que eso tenía y lo que suponía para otros escuchar sobre la “Dischord House”. Es algo parecido a la casa de Peter Pan, donde los niños podían hacer lo que les diera la gana.

Aclaremos esto. El 3819 de Beecher Street era la casa de los padres de Ian y la Dischord House era una casa grupal que empezó en Arlington, Virginia en Octubre de 1981, donde Ian, Jeff, Eddie Janney, Mark Sullivan y Tomas Squip dieron comienzo a todo. The Metro acababa de abrir hacía un año, así que era bastante sencillo llegar a cualquier lado y dormir era realmente barato. La casa estaba aislada, así que las bandas podían practicar en el sótano sin molestar a los vecinos. Además el DC contaba con un índice criminal bastante alto así que la posibilidad de que les robaran el equipo era menor en Arlington que en Washington.

Era genial y había gente bastante divertida. Era una especie de secreto, porque todo el mundo siempre pensaba que estaba en Washington DC, pero realmente estaba en Arlington. Hubo un momento, en el que se podía ir en bici entre casas para ir a pasar el rato. No hacía falta ni conducir, era como nuestro pequeño vecindario conectado.

“Pump Me Up” expo. Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2012. comisario: Roger Gastman

No creo que la gente falta de ideas tengan falta de mano para hacer cosas de calidad. Y más en la música, donde existe esa competitividad de tener una idea y querer que todo el mundo la escuche. Aún queda algún rastro de esa competitividad y creo que es muy sano. Ese intercambio de ideas era más que fantástico ya que muchos de los lanzamientos de Dischord eran muy profesionales.

Había cierto intelectualismo en marcha, sobre todo porque había gente que iba a colegios alrededor del área del DC como Georgetown y George Washington University etc. Lo más sorprendente es que no había ninguna emisora de radio que apoyase esta escena.

Esa falta de atención encendió la llama. Estábamos siempre como escondidos en lo underground que era una mezcla de reto y beneficio para nosotros. Puede que ese intento de hacer que se oyese esa voz y se nos respetara nos mantuviese más unidos como comunidad… no estoy segura.

Algo que me sorprende de verdad es que fueses capaz de invertir 20,000$ en 1987 para la primera impresión del libro. Es como el doble de lo que se invertiría ahora, ¿Cómo fuiste capaz de reunir tanto dinero?

Mientras crecía en LA me di cuenta de que si tenías dinero, tendrías libertad para crear. Cuando me mudé a DC, iba a conciertos de punk y todos lanzaban sus propios records y creaban sus propios flyers y comprendí que hacía falta dinero si quería crear algo. Cuando tenía 14 o 15 años en LA, empecé a trabajar en cualquier cosa que un niño pudiese trabajar y luego, en el DC trabajé en una puesto de flores y ahorré mucho dinero…hasta los 20000 en cosa de 5 años. Además, desde los 16 a los 21 viví en casa de mi madre, así que al no tener que pagar un alquiler, no fue tan difícil. Muchos chavales no fueron tan afortunados como yo. Así que pude ahorrar el dinero, lo gasté en el libro y después tuve que gastarlo de nuevo para la siguiente tirada.

Ginger & Ian. Foto: Amy Pickering

Cuentas que querías lanzar este libro porque deseabas capturar los sentimientos que experimentaste con lo que sucedía. Cada uno tendrá sus interpretaciones después de ojear las fotos y leer las historias que los acompañan, ¿pero qué significan para ti?

El sentimiento es lo que quería preservar… en tu libro (Radio Silence: A Selected Visual History of American Hardcore), lo describo como un tipo de ola, que es algo tonta, porque por primera vez me di cuenta de que era algo que pasaba de repente, no hacía falta seguir presionando. Una cosa iba detrás de la otra, alimentábamos cada cosa que creábamos. Había una energía que crecía constantemente y eso es lo que quería capturar en el libro. Su energía y la comunidad que la creó. Es aún emocionante al leerlo, lo humaniza.

Las historias tratan de personas y de cómo cada uno de esos individuos aportaba algo, ésa energía que un grupo de gente puede crear y sus consecuencias positivas, que parecen no acabar nunca es lo que he tratado de capturar.

¿Qué significa para ti tener este proyecto impreso de nuevo?

Que cada persona que existe tiene un impacto en nuestro modo de vivir. Creo que cada uno de nosotros tiene la capacidad de alcanzar metas más grandes. No solo metas relacionadas con el dinero o algo similar, si no sobre crear un lugar mejor, un lugar mejor en el que vivir. La gente que me ha escrito diciéndome lo mucho que el libro les había influido en la dirección que quieren tomar en su vida. Es una pasada que a día de hoy, haya gente que me cuente que acabaron haciendo cosas como trabajar para un comedor social después de leer el libro. Para mí eso lo es todo.

Cynthia y su hermana en DC, 1981

“Pump Me Up” expo. Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2012. comisario: Roger Gastman

Minor Threat inside sleeve

Minor Threat lyric sheet detail

Nothing Sacred. 1981

Artificial Peace. 1981

Ed, Janelle’s house, summer 1981

Vivian, Toni & Giovanna. 1981

English:

DISCUSSING THE ONGOING INFLUENCE OF “BANNED IN DC: PHOTOS AND ANECDOTES FROM THE DC PUNK UNDERGROUND (79-85)” WITH CYNTHIA CONNOLLY.

Now in its seventh printing, Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes From the DC Punk Underground (79–85) has become part of of American punk rock’s visual language. Spearheaded by Cynthia Connolly, along with Leslie Clague and Sharon Cheslow, the book is a journey into more than just the salad days of the Washington, D.C. punk scene, but a gripping narrative about an inspired youth culture, feeding off their collective energy.

While the images and text perfectly frame the spirit of one of the world’s most storied punk scenes, the larger sentiment is what Banned in DC has come to symbolize—a printed record and story of a truly youth driven, DIY culture, compelled to create. In speaking to Connolly, I mentioned my entry point to the book in the early-’90s and how it made the D.C. scene seem larger than life. Decades removed from its original printing, in an age where the relevancy of print is debated ad infinitum, Banned in DC acts as a flashpoint for those interested in pursuing alternate paths. Like any great piece of art, the book connects individuals who share their love of the book and the scene it documents, creating a vibration and sound that cancels out so much of the noise and stagnation in pop culture.

If you love Banned in D.C., it’s a signal to others that documentation, preservation, serves as tenets of inspiration. Having works such as Banned in DC: Photos and Anecdotes From the DC Punk Underground (79–85) in print, is more than homage or nostalgia—it’s a testament to the possibility of what can be achieved independently, when things need to happen and how that work can continue to move the needle.

You mention in the book that you were looking for an alternative to the macho, male dominated rock ‘n’ roll scene you saw around you as a teenager in LA. Did you find that in LA’s emerging punk scene right away?

I did find it immediately, because a lot of women were in bands. There were obviously more guys involved with it than there were women at the time, but because my perspective was based in California, I thought we were ahead, not where we were, but as “California forward thinking.” So, even if it wasn’t in the immediate, I always felt that it was easily in my grasp. There were women directors—there were a lot of women doing things in other industries and positions in Los Angeles. So, I guess I felt as though it could be easily had in Los Angeles.

Going to D.C., it was probably the same percentage of women and guys being involved with the punk music scene in D.C., but then of course there’s the shift that I talked about that happened June of 1981. There was a show at the 9:30 Club with local punk bands, Minor Threat, Government Issue and Artificial Peace. Most shows before that were at smaller local bars that were not known musical venues. It was at this show that kids from out of town: New York and Boston, etc They danced more violently and that began what I recall was the more violent styles of slam dancing. After that, I became less interested in the music and the activity happening near the stage and became more and more focused on the over all people who were there. So, you could catch me outside talking with people a lot. A lot of women did this, and the guys set out to be violent and dance. So, there was a pretty big shift that happened there, and honestly, happened all over the US around the same time in the differnet punk scenes.

As a result, I took photos in 1981 with a borrowed camera (my camera was stolen in Los Angeles) because I didn’t see a lot of people taking photos. I stopped taking photos when other people started taking photos in about 1982. I also started going to college/Art school.

I contributed in the scene by being there, helping at Dischord fulfilling mail order, and lending them money on occasion for some of their releases. (Flex Your Head, which was a big deal, as it was the first 12” LP released by them at that time). Additionally, in 1983, I drew the black sheep on the cover of the Out of Step EP.

Did you see the punk scene as an extension of the art scene happening in Los Angeles at the time-sort of a new medium to explore?

Well, I did see the dialogue mesh or combine, because of the fact that the entertainment industry is in Los Angeles—the larger creative field that includes film set design, costume design, performance and music, and then contemporary art. The lines are blurred for all of that in Los Angeles. There was a lot of crossover. There was a new wave scene—people into clothing design and fashion, obviously involved in this alternative music scene in Los Angeles, who were opening up their own shops on what became “the” Melrose Avenue. The first trendy shops back there were the ones that were punk/new wave shops —nobody else was really designing clothes like that.

Washington D.C. is not really a creative city at all. It’s a political city and so, if there is any creativity it’s all in politics. A different ball of wax entirely. It’s a bit more conservative . Ronald Reagan was just being elected and that was a whole different tone.

Because D.C. was more conservative did it make the punk scene more creative… more reactive?

It was more reactive to the landscape we were placed. That’s actually what’s so compelling to me about Washington D.C. and still is —there’s a challenge to make something happen in a place where you don’t see it being very creatively fertile. That’s always what I thought was fun about it from the punk scene too, because when you did actually encounter somebody else who was interested in it, it was actually pretty exciting, because those people seemed few and far between.

An example that I learned from research for the Banned in DC book: The story of the Bad Brains being interested in the Sex Pistols, having heard them on, I believe, WGTB, the Georgetown radio station, then from that discovery, gravitating and finding the punk scene in DC, then other kids discovering the bad brains in D.C.—they just fed off each other. In the late-70s/early- 80s D.C. was a whole different place than it is now 35 years later. It was racially divided, it still was economically and severely depressed from the riots of the 60s. Then, there were rotting buildings downtown and now they are vibrant. The 9:30 club and D.C. Space were downtown, because there were so many vacant in buildings it was an inexpensive have a club there and that was where the owners of the clubs lived.. just near their businesses. The location where dc space is, is now a a Starbucks and the old 9:30 Club location is a J. Crew, if that gives you an idea of the economic change that’s occurred.

With art being created in such an oppressive and conservative environment, there are definitely people that could look back on the idea of “straight edge,” as a conservative ideal.

I met Ian after he wrote that song and right before it was released. It was a reaction of his own experiences growing up, as were all the songs. That song could be considered conservative, but in some way was radical at that point in time, coming out of the 70’s and 60’s where I knew friends of mine raised smoking pot with their parents in the era of what I might call having “limited boundaries”. “Straight Edge” proclaimed a set of rules that your parents were expected to set, but in this time period were discussed by the children of the parents whose parents NEVER set any rules. Anyone who grew up then would know. In the end, Ian saw drinking as a waste of time, in particular. We all know that youth is wasted on the young. Ian was extremely young to make such a bold statement. He was passionate and reacted to the environment around him.

Because he was “Straight Edge” he was exceedingly productive as a kid. He wasn’t drinking all the time and hanging out, fucking up. There was a time where there were lots of people who loved to drink and get fucked up, so there was a tension between the friends that we knew, when that song became highlighted.

It was one of many songs and that one was the one that got pulled out. In the long run, we all grew out of the reactive stance with that song. It’s hard for me to say when you’re about that song, as far as culturally over the long period of time, because it just goes on and on.

There were a lot of people that were older than us at the time, who were involved with that new wave, earlier punk scene that got involved with heroin. A lot of them died or ended up getting diseases spread by sharing needles. When you think about it, it the “straight edge” movement really does run parallel to the timing of Nancy Reagan’s ‘Just Say No’ campaign, but they’re completely separate. I don’t think either we’re influenced by the other. A really funny coincidence is that my mother moved to D.C. to work for Reagan, and when Ian and I were first going out, she even had some of the first ‘Just Say No’ meetings at her house.

To me the larger message is about the idea of productivity. People see the era of D.C. hardcore in your book as a symbol of documentation and productivity. I’m curious to hear your perspective on how people see and covet that time.

People have been talking a lot recently about the heavy documentation that was done of this time period by the participators. An interesting influence for the MacKaye kids might just be their mother. Ian’s mother and father were both writers and his mother in particular had stored, in a very organized fashion, notes on her life and children in two, four-drawer filing cabinets. Ian’s mother would talk about her filing cabinets and pull journals and notes that she wrote as her children were growing up to reminisce and of laugh about them. His mother was always really enjoying life as it happened, but also documenting and then coming back, not too soon afterwards, pointing out amusing things like her journal entry for going to the Slinkees show or other similar events. Her perspective of the whole scene was fun to hear.

As for her documenting, I’m sure that had great influence on Ian, Alec, and Amanda MacKaye in particular—the three siblings who were mostly involved in the punk scene of the five kids—and then and then it influenced me too, because I was there all the time. I admired her type of “database,” that she had before there was an actual database for this type of material. She’d take something out and talk about it and reference it instantly from this filing system that she had. I write about in the afterword, because I don’t think she gets as much credit, not only for her system of documenting but also the way she set up the home and allowed kids to hang out. The door was always open and people could go and hang out there and it provided a safe space for some kids who needed a place to go. She really enjoyed that activity and embraced it.

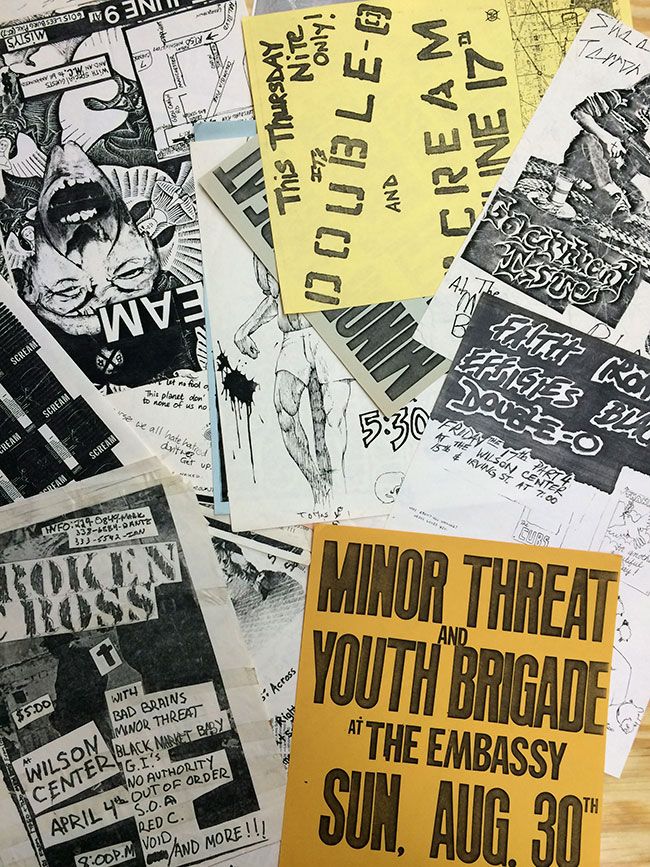

I am really not sure if anyone knew about her system of story collecting, but there were others in the scene that were collecting and organizing ephemera. Like Tom Berard, a huge music fan and deejay, would obsessively would bring every single album to every show and get them signed. I can’t even imagine what his collection is like at this point with the amount of things he has signed. Jeff Nelson was very close to Ian. He was meticulous from the get go, had a very organized system of collecting things from the scene. I always admired his focus on collecting things and then being able to pull out the right thing at the right time and know where it is stored.

When you mention having this house as kind of a hub for the scene, it really makes me think about how important that was and what it meant to other people who hear about the “Dischord House.” It’s almost like this whimsical Peter Pan place, where kids can just do what they want.

Just to clarify here. 3819 Beecher Street was Ian’s parent’s house and the actual Dischord House was a group house that was started in Arlington, Virginia in October 1981, where Ian, Jeff, Eddie Janney, Mark Sullivan, and Tomas Squip started a group house. The Metro had just opened maybe the year before, so it was easy enough to get places and the rest was really inexpensive. The house was separate and bands could practice in the basement and not bother the neighbors. Also D.C. had higher crime, so the chance of the equipment being stolen was far less in Arlington than it would in D.C..

As Dischord Records grew, some of the tenants of the original group house moved out, that space was used by the record company. I moved in there in 1987 and eventually what happened sometime after I moved in, the base of operations for Dischord moved across the street to a basement space underneath a 7-Eleven. What was interesting about Dischord was that other record labels like Teen Beat, which was always in Arlington because Mark Robinson grew up in there, and there was Simple Machines, so in the late 80s there were at least three record labels and also other group houses like Positive Force. It was just the perfect economic time where it was inexpensive to live in Arlington to live in a group house. Because of the group living it gave you the opportunity to save your money and for me and do my artwork or to do record labels or to be in a band or to travel. It was a really cool readjustment of your perspective of priorities of what you want to do in your life. Instead of worrying about climbing the socioeconomic ladder so-to-speak, you’re investing your time in a community that was mostly music or art focused.

It was a really cool and fun network of people. It was kind of a secret, because everybody always expected it to be in Washington D.C., but it was in Arlington. At one point you could ride bikes to one house to the other and hang out. You didn’t need to drive. It was like our own little neighborhood connected somehow. It eventually shifted when the rent went up and people found other inexpensive places to live, including DC. What do you think it is?

I don’t think people lack ideas they lack execution. In music it sometimes is competitive You have an idea to get out you want people to hear it. There’s still something a little competitive about it and I think that healthy competition, that exchange of ideas that’s community and as you said, the shifting of priorities, when you see it executed so well it’s inspiring. Also, it’s all rooted in the music of D.C. which was not only fantastic, but many of the Dischord releases looked so wonderful and professional. It raised the bar—they’re timeless and that’s why people still connect to them.

There was some intellectualism going on, especially because some people went to colleges around the DC area like Georgetown and George Washington University, and more. What’s so fascinating is that there was no radio station that supported this scene. That lack of attention fueled the fire. We were always sort of hidden and in an underground, which was challenging but also beneficial. That friction of trying to make our voice heard or respected kept us going and kept us more as a close knit community than perhaps other scenes? I am not sure.

OK, something else that really stood out to me, was that you were able to invest $20,000 in 1987 for the first print run of the book. That’s worth more than double by now, if you throw it into the inflation calculator. How were you able to get that money together?

When I was growing up in L.A. I thought that you know if you have money – it gives you the freedom to create. When I moved to D.C. I was going to punk shows and understood that people were putting out their own records and making flyers, and that there was a need for some kind of cash flow for me if I wanted to create something. When I was 14 or 15 in LA, I started working in any job a kid could get and then in D.C, I worked at a flower stand and then a record store and saved a lot of money… to the tune of $20,000 over five years. From 16 to 21-years-old I lived at my mom’s house during that time, so I wasn’t paying rent and that helped out as well. Some kids aren’t as fortunate as I was. So was able to save that money, spend it on the book, and then I had to spend it again for the next printing.

What’s the feeling of being like 21 years old and putting your life savings on the line to put out this book? I’d still be terrified no matter what.

I just knew it had to happen. I didn’t really think about it, being bad or scary. There was a moment where I wrote a check and thought, ‘Goddamn it! That’s a lot of money!’ It’s still a lot of money. Then I realized I needed somewhere to store these books, so the first printing went into my mom’s basement. D.C. is so humid, I had to buy a dehumidifier to protect that investment of printed paper! I realized at that minute that if these get destroyed I’m throwing away $20,000, right? No insurance policy on it! Of course it totally terrified me. That’s when it actually scared me, so I got more aggressive on selling them.

You mention that you wanted to do this book because you were trying to capture the feeling of what was going on. Everyone’s going to have their interpretations after looking through the photos and reading the blurbs that accompany them, but what does it really mean to you?

The feeling is what I was trying to preserve. … in your book (Radio Silence: A Selected Visual History of American Hardcore), I described it as some kind of wave, which is kind of silly, but it was the first time I realized there’s something that happens and all of a sudden it’s no longer something you’re pushing—it’s now it’s like a raft that’s gone into floating and is floating away, that you have no control over, but it’s more aggressive than that. (Perhaps more like white water rafting!) There’s this excitement—somebody would put on record you’d be excited about everything. One thing after the other, we fed off whatever we were creating. There was an energy that escalated constantly and that is what I wanted to capture in the book. Both the energy and the community that created it. It’s still exciting to read it. It humanizes it. The stories are really about individual people and how these individual people make something—that energy that a group of people can create and the positive outcomes, which are never ending at this point.

What does it mean to you to have this project in print again?

The fact that every single person in existence has an impact on the way we all we all live. I believe that each one of us has the capacity to reach higher goals and you can ever imagine. Not goals of making money or that kind of thing, but it’s about creating a better place—a better place to live. People who have written to me saying how the the book is influenced their direction and where they want to focus their time and their life. It is really excting that to this day, that people write to me and tells me that they ended up doing something like working for a homeless shelter, because they read the book. That’s the whole point

www.cynthiaconnolly.com