(English below) Tratar de definir a Jeff Johnson no es tarea sencilla. Es una especie de hombre del renacimiento, que pone cuerpo y mente al servicio de su pasión por las actividades al aire libre. Avezado surfero, skater, escalador, escritor, fotógrafo y cineasta; se ha convertido, casi sin pretenderlo, en una de las figuras claves para entender el auge de la industria del outdoor, ayudando a fijar en el imaginario colectivo un ideal en torno al estilo de vida que estas actividades representan. Su capacidad de contar historias, a través de cualquiera de los medios que utiliza es, sin duda, algo en lo que destaca y que le ha dado la posibilidad de trabajar con marcas como Patagonia, Leica, Roark, Yeti o St. Archer Brewing, entre otras.

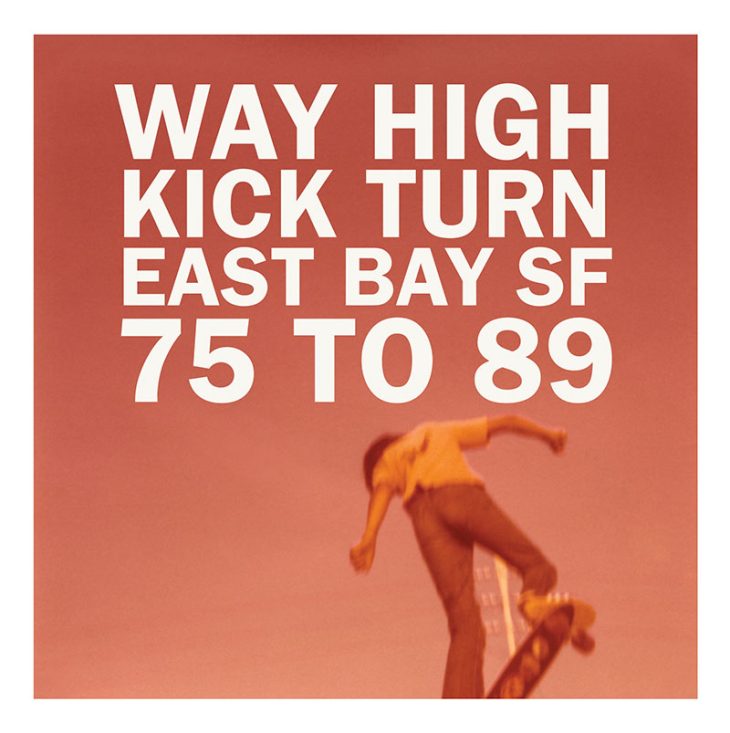

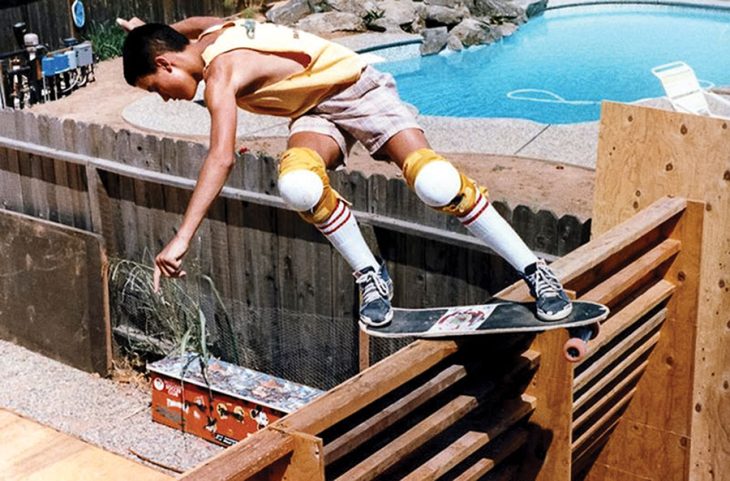

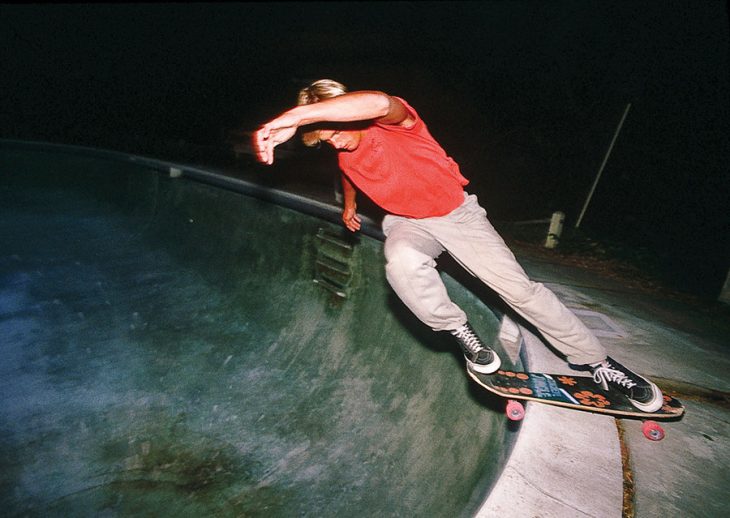

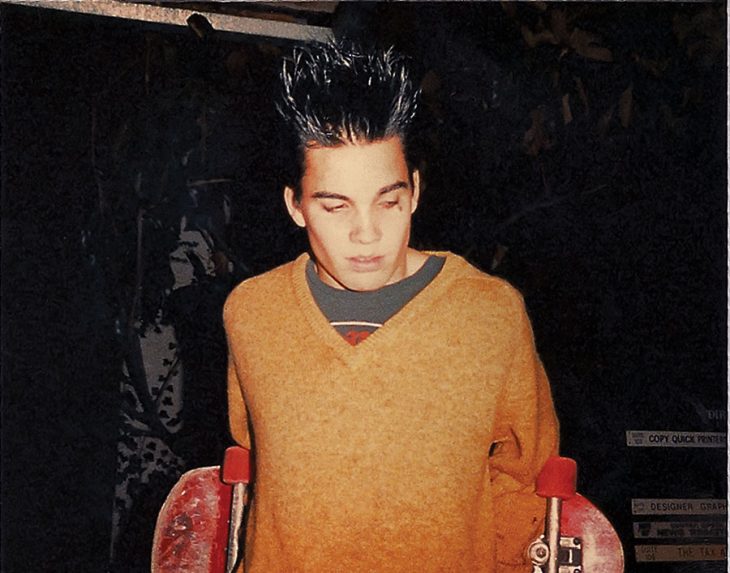

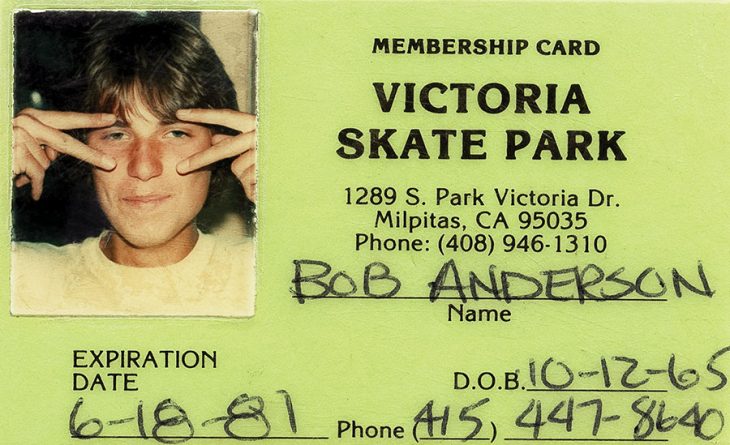

Una parte fundamental para entender su carrera y su desarrollo vital, posiblemente la más trascendente, transcurre entre los años que parecen en el título de su último libro, WAY HIGH KICK TURN EAST BAY SF 75 TO 89, publicado por Beyond and Back Press. Un viaje a un tiempo y un lugar muy concretos, un tributo a la cultura de skate entre los años 70 y 80, en el que se retrata a un joven grupo de skaters del East Bay. Como el mismo relata, aquellos años le ayudaron a conformar su visión del mundo y se convirtieron en un marco de referencia para el resto de su vida.

Este proyecto tiene un origen curioso, un email, un video de YouTube, una cadena de emails a través de la cual se comparten imágenes antiguas…¿qué nos puedes contar sobre ello? ¿En qué punto decides que podía ser algo más que una conversación entre viejos amigos?

Fue un correo electrónico que recibí en 2007 con un enlace a Youtube, un vídeo de mis amigos y yo patinando en una piscina del patio trasero en 1987. Había unas 15 personas en esa cadena de correos electrónicos, chicos a los que no había vuelto a ver desde aquella sesión en la piscina. Esto fue antes de que todo el mundo estuviera en Facebook. Todos los participantes empezaron a escanear sus fotos antiguas y a adjuntarlas a la cadena. Las fui subiendo a mi escritorio y al final tenía una carpeta con unas 300 fotos. Periódicamente me desplazaba por ellas como si fuera una presentación de diapositivas. Con el tiempo me di cuenta de que aquí había algo especial, digno de un libro.

No creciste en Venice Beach, Santa Cruz o San Francisco. Perteneces a ese grupo de raros, de entre los raros, que creció en los suburbios, en lugares que no salían en las revistas. ¿Cómo recuerdas la escena de skate de East Bay y cuándo y cómo empezaste a formar parte de ella?

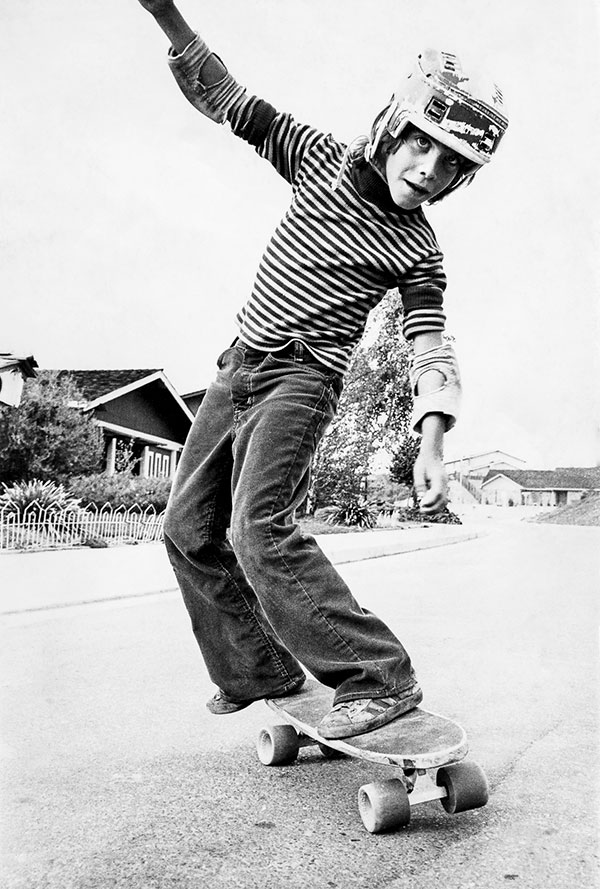

Me inicié en el monopatín a mediados y finales de los 70: patiné en algunos parques, construí algunos quarter pipes en la entrada de mi casa, etc. Pero también monté en BMX, jugué al fútbol y al béisbol. Alrededor de 1981 o 1982 escuché algunos de mis primeros discos de punk rock y, esa música, esa energía, lo cambió todo para mí. Me corté el pelo, dejé todos los deportes organizados y me compré un monopatín nuevo… Y eso fue todo. No éramos muchos. Estábamos fuera de la “escena” por ser de los suburbios. Pero todos nos encontramos de alguna manera. Nuestro pequeño grupo fue creciendo, tanto que la revista Thrasher envió a un fotógrafo para que nos fotografiara a todos delante de nuestra tienda de skate local, que era una tienda de ropa que vendía unos cuantos monopatines. Esa foto en blanco y negro apareció en Thrasher, está al final del libro.

En este libro, abres una puerta a tu pasado, a tus recuerdos de juventud. ¿Lo ves simplemente como ejercicio de nostalgia o piensas que entender aquello, lo que pasó en esos años, nos puede ayudar entender muchas cosas del presente?

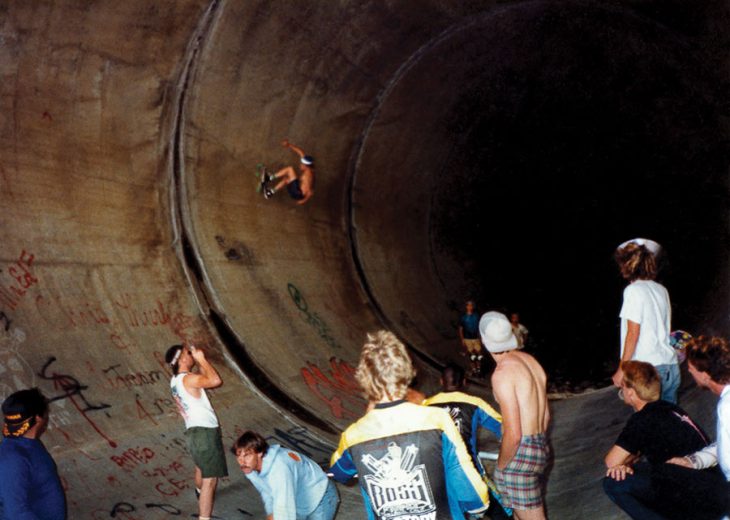

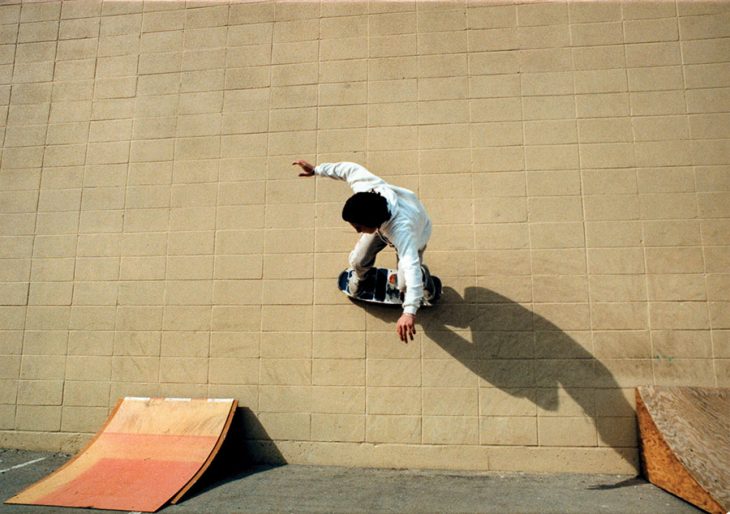

Creo que es tanto un ejercicio nostálgico como un documento importante de una época definitoria. El skateboarding se estaba volviendo muy comercial a finales de los setenta. En 1980 todo se vino abajo: casi todos los skateparks cerraron, muchas empresas de skate se hundieron y todas las revistas de skate desaparecieron. De repente, el skate pasó a ser underground. Cuando resurgió unos años más tarde, era diferente, ya no se parecía a esa cosa brillante y colorida inspirada en el surf de los años 70. Ahora era oscuro. La actitud era cruda. Las tablas eran más anchas, la música era más dura. Y ahora teníamos la revista Thrasher, que era la nueva voz que incorporaba tanto la música como la actitud. Si el skateboarding no hubiera tenido esta caída, esta revisión a principios de los 80, habría tomado un camino completamente diferente. Y este libro es una mirada a esa época a través de la lente del skater cotidiano de entonces.

¿Eres de los que piensas que cualquier tiempo pasado fue mejor o puedes identificar, objetivamente, elementos que definan aquel momento como algo único e irrepetible?

No creo que fuera mejor entonces, sólo diferente. Pero hay algunos elementos que, en retrospectiva, hacen que la época sea única. Por ejemplo, hay tantas cosas buenas para patinar hoy en día; hay skate parks en casi todas las ciudades, los parques DIY se ven como algo normal y, a veces, incluso se fomentan, hay campamentos de skate y escuelas de skate. Tantas oportunidades y tantas opciones que siento envidia, ¡ojalá tuviera 13 años otra vez! A principios de los 80 no teníamos ningún sitio donde patinar a menos que lo encontráramos o lo hiciéramos nosotros mismos. Construíamos nuestras propias rampas, vaciábamos las piscinas de los patios traseros, barríamos tuberías llenas y zanjas de drenaje. Patinar en la calle era ilegal en algunas ciudades: patinando por la acera te podían detener y quitar el monopatín. Pero esta falta de terreno también hizo que la época fuera muy especial, porque teníamos que ser autosuficientes e ingeniosos. Creo que fue una especie de época dorada, y sí, irrepetible.

Desde luego debieron ser unos tiempos muy especiales, marcados por una realidad social, política y económica muy concreta. En este contexto, el patín, la música, la estética, etc. servían, de algún modo, como vehículo para expresar vuestra posición frente a la corriente dominante. ¿Teníais la sensación de ser vosotros contra el mundo?

No creo que ninguno de nosotros pensara que éramos nosotros contra el mundo. El mundo no sabía lo que hacíamos, y no nos importaba si lo sabían o no. Era muy bonito participar en algo relativamente anónimo, te sentías parte de algo especial. Por supuesto, nos enfrentábamos a la policía, a los profesores de nuestros colegios, a los deportistas, a los paletos, etc., pero sobre todo por nuestro aspecto y nuestra forma de vestir. Nosotros mismos nos lo buscábamos al mandar a la mierda la estética que se daba por aceptada.

En esta época se produce un cambio fundamental, sois el germen de una nueva cultura emergente cuyas reglas estáis creando vosotros mismos. Hay un elemento de pureza, de inocencia, de inconsciencia, que parece fundamental. Casi sin saberlo, estabais poniéndolo todo patas arriba. ¿En qué momento eres consciente de la trascendencia de todo esto?

Como procedíamos de los suburbios, mayoritariamente conservadores, algunos éramos muy conscientes de que estábamos poniendo las cosas patas arriba. Era una rebelión directa contra nuestros padres de la generación del baby-boom. Pero el monopatín era todavía muy joven, quizá tenía una década. No teníamos referencias históricas. Simplemente lo hacíamos. Hay que recordar que los patinadores más veteranos tenían entre 20 y 30 años. No teníamos ni idea de hacia dónde iba todo esto. Soy consciente de que había gente patinando a finales de los 50 y los 60, surfistas imitando el surf, pero hasta los 70 el skate no tomó su propio camino.

¿Cómo crees que todo aquello que viviste junto a tus amigos, aquellas vivencias y experiencias, han determinado la persona que eres y lo que haces a día de hoy? En otras palabras, ¿cómo crees que ha influido todo aquello en tu desarrollo personal y profesional?

La escena punk rock del monopatín de los 80 estaba plagada de caos y era algo violenta, pero también había un sentimiento generalizado de camaradería, integridad y honestidad. Si no eras tú mismo al 100%, te lo decían. Era una ética de no hacer tonterías que me ha acompañado hasta hoy. Ha contribuido a determinar quién soy, la gente que me atrae y el tipo de trabajo que me gusta hacer. Y sé que todas las personas con las que crecí patinando sienten lo mismo. Creo que mi vida habría sido muy distinta sin el monopatín.

Más allá del libro, y aprovechando esta oportunidad, nos gustaría preguntarte algo sobre los proyectos en lo que andas actualmente inmerso. Te hemos visto últimamente colaborando en algún proyecto con Chevrolet, pero también con SeaVees, Leica….¿Cuál es tu relación con estas marcas y cómo eliges tus colaboraciones? ¿Sigues trabajando con Patagonia?

Trabajé en Patagonia durante 13 años como su primer fotógrafo de plantilla y ayudé a lanzar Patagonia Surf con los hermanos Malloy en 2006. Conseguí mi primera Leica en 2007 y he colaborado con la marca desde entonces. Seavees es una marca local de calzado de Santa Bárbara anterior a Vans. Hemos aunado esfuerzos para crear mi calzado característico, la Beyond and Back Boot. Hasta ahora hemos lanzado 3 temporadas, la más reciente este otoño. Hace poco hice un trabajo para Chevrolet, pero yo no lo llamaría una relación… todavía. He hecho más trabajos para la empresa de vehículos eléctricos Rivian. Colaboro estrechamente con la marca de ropa Roark, con la que viajo mucho y en la que trabajo con gente estupenda. Y he estado trabajando con Yeti, por contrato, durante los últimos 8 años. En realidad, no hago publicidad de mi trabajo, aparte de algunas publicaciones en las redes sociales y mi sitio web, que no se actualiza desde hace años. Casi todo mi trabajo viene del boca a boca y de amigos de amigos.

Podríamos terminar preguntándole algo sobre su visita a España, de esto no tengo mucha información. ¿Cómo lo ves?

He estado en España dos veces. Una vez con Patagonia, donde estrenamos la película 180 South en San Sebastián. La otra durante un viaje de surf con mi mujer y mi hijo. Estoy emocionado por ver Madrid y todo lo que hay en Moments.

Más información:

www.jeffjohnsonstories.com

www.beyondandbackpress.com

English:

JEFF JOHNSON

Trying to define Jeff Johnson is no easy task. He is a kind of renaissance man, who puts body and mind at the service of his passion for outdoor activities. An avid surfer, skateboarder, climber, writer, photographer and filmmaker, in any of these facets he stands out and has become, almost unintentionally, one of the most relevant and influential figures in the outdoor industry as a content creator. With a very clear idea, to generate quality content for an audience that identifies, above all, with the stories and, from there, with the products. His work with brands such as Patagonia, Leica, Roark, Yeti or St. Archer Brewing, among others, has had a fundamental transcendence in the construction of an ideal around the due style that these activities and their practice represent.

Trying to define Jeff Johnson is no easy task. He is a kind of Renaissance man, dedicating his body and mind to his passion for outdoor activities. An avid surfer, skateboarder, climber, writer, photographer and filmmaker, he has become, almost unintentionally, one of the key figures in understanding the rise of the outdoor industry, helping to establish an ideal in the collective imagination around the lifestyle that these activities represent. His storytelling ability, through any of the media he uses, is undoubtedly something he excels at and has given him the opportunity to work with brands such as Patagonia, Leica, Roark, Yeti, and St. Archer Brewing, among others.

A fundamental part of his history, possibly the most transcendent, takes place between the years that appear in the title of his latest book, WAY HIGH KICK TURN EAST BAY SF 75 TO 89, published by Beyond and Back Press. A journey to a very specific time and place, a tribute to the skate culture of the time where he portrays a young group of East Bay skateboarders. As he recounts, those years helped shape his worldview and became the framework for the rest of his life. He is drawn to subcultures; the underground, the underdog, people who are honest with themselves and their approach to life.

This project has a curious origin, an email, a YouTube video, an email chain through which old images are shared…what can you tell us about it? At what point did you decide that it could be something more than a conversation between old friends?

It was an email I received in 2007 with a link to Youtube, a video of my friends and me skating a backyard pool in 1987. There were about 15 people on that email chain, guys I hadn’t seen since that pool session. This was before everyone was on Facebook. All the guys on the email started scanning their old photos and attaching them to the chain. I was pulling them onto my desktop and eventually I had a folder with around 300 photos. I would periodically scroll through them like a slide show. Eventually I realized there was something special here, worthy of a book.

You didn’t grow up in Venice Beach, Santa Cruz or San Francisco. You belong to that group of weirdos, of the weirdos, who grew up in the suburbs, in places that weren’t in the magazines. How do you remember the East Bay skate scene and when and how did you become a part of it?

I dabbled in skateboarding in the mid to late 70’s—skated some parks, built a few quarter pipes in my driveway, etc. But I also rode BMX bikes, played football and baseball and soccer. Around 1981-1982 I heard some of my first punk rock albums and that music, that energy, changed everything for me. I cut off all my hair, quit all organized sports, and got a new updated skateboard—and that was it. There weren’t a lot of us. We were outside of the “scene” being from the suburbs. But we all happened to find each other somehow. Our small crew just got bigger, so big that Thrasher magazine sent out a photographer to take a photograph of all of us in front of our local skate shop, which was a handwear store that sold a few skateboards. That black and white photo appeared in Thrasher, it is at the end of the book.

In this book, you open a door to your past, to your memories of your youth. Do you think it’s an exercise in nostalgia or do you think that understanding what happened in those years can help us understand a lot of things in the present?

I think it is both a nostalgic exercise and an important document of a defining era. Skateboarding was getting very commercial by the end of the 1970’s. By 1980 everything had fallen apart; almost all the skateparks had closed, a lot of skate companies went under, and all the skate magazines had disappeared. Skateboarding was suddenly underground. When it resurfaced a few years later, it was different, it no longer looked like that bright and colorful surf-inspired thing of the 70’s. Now it was dark. The attitude was hardcore. The boards were wider, the music was harder. And now we had Thrasher Magazine, which was the new voice that incorporated the music as well as the attitude. If skateboarding didn’t have this downturn, this check in the early 80’s, it would have taken an entirely different path. And this book is a look at that era through the lens of the everyday skater of that time.

Are you one of those who think that any past time was better or can you objectively recognize elements that really define that moment as something unique, unrepeatable?

I don’t think it was better back then, just different. But there are some elements that, in retrospect, make the era unique. For instance, there are so many great things to skate nowadays; there are skate parks in almost every town, DIY parks are being excepted and sometimes encouraged, there are skate camps and skate schools—so much opportunity and so many options that I am jealous—I wish I was 13 years-old again! In the early 80’s we didn’t have anywhere to skate unless we found it or made it ourselves. We built our own ramps, drained backyard pools, swept out full pipes and drainage ditches. Street skating was illegal in some cities—just skating down the sidewalk you could get arrested, and your skateboard taken away. But it was this lack of terrain that also made the era really special because we had to be self-reliant and resourceful. I feel it was sort of the golden era, and yeah, unrepeatable.

Of course they must have been very special times, marked by a very specific social, political and economic moment. In this context, skateboarding, music, aesthetics, etc. served to express your discomfort against the mainstream, your position. Did you have the feeling that it was you against the world?

I don’t think any of us thought it was us against the world. The world didn’t know what we were doing, and we didn’t care if they knew or not. There was a lot of beauty in being involved in something that is relatively anonymous, you really felt like you were part of something special. Of course, we were up against the cops, the teachers at our schools, the jocks, the rednecks, etc. but that was mostly because of the way we looked and dressed. We were bringing it onto ourselves by saying fuck-off with our general aesthetics.

At this time there is a fundamental change, you are the germ of a new emerging culture whose rules you are creating yourselves. There is an element of purity, of innocence, of unconsciousness, which seems fundamental to us. Almost without knowing it, you were turning everything upside down. At what point are you aware of the transcendence of all this?

Being from the suburbs which were largely conservative, some of us were acutely aware that we were turning things upside down. It was a direct rebellion against our baby-boomer parents. But skateboarding was still very young, maybe a decade old at this point. So, we had no historical reference. We were just doing it. You have to remember, the oldest skaters at the time were still in their 20’s and 30’s. We didn’t know where it was going. (I realize there were people skateboarding in the late 50’s and 60’s, surfers imitating surfing. But it wasn’t till the 70’s that skateboarding became its own thing)

How do you think that everything you lived with your friends, those experiences, have determined the person you are and what you do today? In other words, how do you think all this has influenced your personal and professional development?

The skateboarding punk rock scene of the 80’s was fraught with chaos and it was somewhat violent, but there was also an over-arching sense of comradery, integrity, and honesty. If you weren’t being 100% yourself, you were called out on it. There was this no-bullshit ethos that stays with me to this day. It has helped determined who I am, the people I am attracted to, the type of work I like to do. And I know that everyone I grew up skating with with feels the same way. Without skateboarding I think my life would have been much different.

Beyond the book, and taking this opportunity, we would like to ask you something about the projects you are currently involved in. We have seen you lately collaborating in some projects with Chevrolet, but also with SeaVees, Leica …. What is your relationship with these brands and how do you choose your collaborations? What’s your actual involvement with Patagonia?

I worked at Patagonia for 13 years as their first staff photographer and helped launch Patagonia Surf with the Malloy Brothers in 2006. I got my first Leica back in 2007 and have been collaborating with the brand ever since. Seavees is a local Santa Barbara shoe brand that pre-dates Vans. We have combined efforts to make my signature shoe called the Beyond and Back Boot. We have launched 3 seasons so far, the most resent shoe this fall. I recently did a job for Chevrolet but I wouldn’t call it a relationship…yet. I have done more work for the electric vehicle company called Rivian. I work very closely with the clothing brand Roark, lots of travel and really great gear and great people. And I’ve been working with Yeti on contract for the last 8 years. I don’t really advertise my work other than a few posts on social media and my website that hasn’t been updated for years. Almost all my work comes from word-of-mouth and friends of friends.

Please, tell us about your visit to Moments festival in autumn, is it your first visit to Spain for “work”?

I have been to Spain twice. Once with Patagonia where we premiered the film 180 South in San Sebastian. The other while on a surf trip with my wife and kid. I’m excited to see Madrid and everything at Moments.