{english below} En el año ‘92 un nuevo sello de música urbana salió a la luz bajo el nombre Mo’Wax. Enfocado en el Trip-Hop, el turntablism y el Hip Hop alternativo, pretendía enriquecer una década ya de por sí prolífica en la que los géneros musicales se combinaban en idilios impensables tan solo 10 años antes. De ese modo, gracias también a la proliferación de los “home studio” (que permitían con pocos medios un acceso a ediciones digitales profesionales) y a una nueva tendencia de composición musical basada en el collage, como era el cut’n’paste, muchos músicos exploraron diferentes caminos que, en su mayoría, apoyados por la electrónica, generaron la punta de lanza de lo que en su momento se consideró la música urbana de vanguardia.

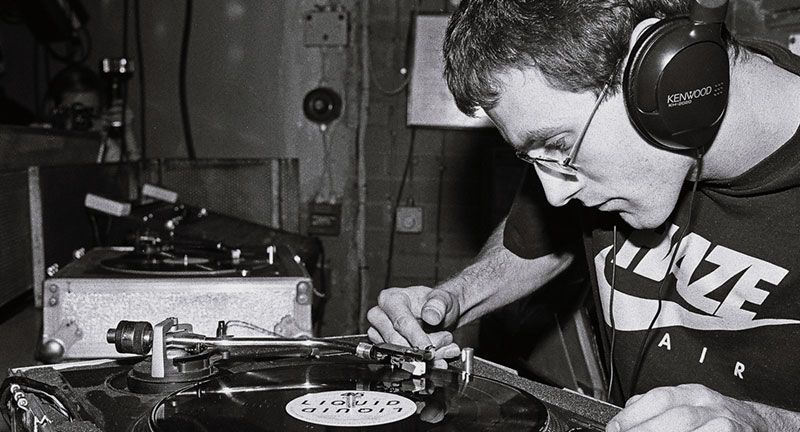

Mo’Wax, fundada por dos jóvenes djs, James Lavelle y Tim Goldsworthy, se propusieron no solo facturar discos en un mero propósito mercantilista, sino que abrazaron la idea de crear una comunidad humana alrededor de esos discos, una comunidad conectada a su vez con la calle y con el arte; una filosofía de colectivo que no era común hasta entonces.

En el ‘96 Mo’Wax lanzó a la calle el disco Endtroducing de Dj Shadow, un disco que generó un éxito inesperado para el sello, y que lo catapultó a lo más alto, convirtiendo a James Lavelle (responsable máximo del meteórico éxito que experimentó el sello) en una figura clave en la escena mundial. Años después, desencuentros a nivel personal y financiero truncaron la continuidad del sello, hundiendo a James Lavelle a una situación en la que llegó a perder todo su catálogo de artistas.

La historia de Mo’Wax y James Lavelle es un relato de éxito y fracaso que el realizador Matthew Jones nos presenta en su nuevo documental ‘The Man From Mo’Wax’. El director, gran conocedor de la historia del sello, y protagonista presencial de muchos de sus actos, ha tenido acceso a gran cantidad de material de archivo nunca visto hasta ahora. Con todo ello ha construido una completa historia del universo Mo’Wax, de la escena musical de la época, y del personaje central James Lavelle, alrededor del cual se desarrolla este periodo de acontecimientos tan importantes en la historia de la música underground de los ’90.

Estuvimos hablando con el director sobre la película, y nos respondió a varias preguntas.

A nuestros lectores que aún no vieron la película: ¿De qué va “The Man From Mo’Wax”?

Se trata del ascenso y el ocaso de James Lavelle. Trata de las amistades que pierde cuando persigue el éxito profesional a cualquier precio. Trata también sobre su reacción ante el éxito masivo, la recreación de dicho el éxito y como se reinventó a sí mismo. La película pregunta: ¿Vale la pena ese éxito si tus relaciones se desmoronan? Es una celebración de la música Mo’Wax, pero lo más importante es un examen conmovedor del poder de la amistad.

¿Cuál fue tu inspiración para hacer esta película?

Me inspiré en la actitud emprendedora de James, y su actitud de venirse siempre arriba. Estaba fascinado con Mo’Wax, su historia, y toda la identidad visual y cultural que James construyó alrededor del icónico sello londinense.

¿Lavelle vio la película? ¿Está feliz con el resultado?

Sí, la ha visto muchas veces. Creo que está contento. Ver tus mayores errores en la pantalla es difícil para cualquiera. No sé si yo podría lidiar con una película como esta sobre mí, así que el hecho de que James esté apoyando el lanzamiento de la película, haciendo apariciones, DJ Sets y atendiendo entrevistas es muy respetable, y se lo agradezco profundamente. Nos dijo que está todo en su sitio, bien montada, y que personalmente le parece muy catártica. Le ha dado cierta perspectiva sobre sus errores y también ha reavivado algunas de sus viejas amistades, lo cual es genial.

Una gran cantidad del material utilizado en el documental proviene del archivo de James Lavelle. Algunas imágenes son muy íntimas. ¿Quiso James intervenir de algún modo el proceso de creación de la película?

Por supuesto, James estuvo involucrado. Es un artista activo y la película fue importante para él. Al mismo tiempo, hice la película que quería hacer, y no permití que James dictara nada sobre la estructura o la dirección de la misma. Dijimos desde el primer día que queríamos hacer un documental honesto. No podría ser adulador. Ya hay demasiados documentales musicales tipo concierto “míra lo guay que soy”, hechos por la industria de la música, y que son básicamente videos publicitarios de 2 horas. Es una pérdida de tiempo. Le mostramos a James los cortes de la película, y él nos ofrecía comentarios, algunos de los cuales eran realmente valiosos. Nos pasaba contactos de personas que aún no habíamos entrevistado, y archivos fotográficos adicionales para ayudarnos a construir la película. Igualmente te digo que a James no le gustó nada la parte de la grabación del disco “Where the nightfall”. Quería cambiarla, le parecía deprimente, pero yo estuve allí, durante la creación de ese cuarto disco, y te confirmo que fue horrible, fue un desastre, no había energía. Las colaboraciones ya no funcionaban, todo se estaba haciendo con artistas a través de Internet. Faltaba alma allí, y por eso salió en el disco que se hizo, y la película refleja eso. Entiendo que es difícil para cualquiera ver como sus sueños no salen adelante como ellos quisieron. El fracaso es parte del mundo creativo. La mayoría de los proyectos fracasan. Las críticas de James a la película son sobre ciertas partes de cuando las cosas no le fueron bien. Es inmensamente difícil ver tus errores proyectados en una pantalla de cine.

James Lavelle como A & R, como estrella de rock, como productor. En tu opinión, ¿fue la mezcla de estos perfiles el fracaso de MoWax?

La razón principal por la que Mo’Wax falló fue el acuerdo financiero que tenían con A&M Records, que terminó en 1998. Mo’Wax se convirtió en un monigote cuando se fusionaron los gigantes Polygram (dueño de A&M) y Seagram (Universal Music hoy). Creo que Mo’Wax habría sobrevivido al James “artista” si el acuerdo financiero de A&M hubiera permanecido en su lugar. El problema fue que perdió a sus artistas y sin esa financiación detrás no pudo respaldar los discos de la forma que quiso. Finalmente, perder la seguridad de Osman Eralp en A&M, y el control de UNKLE, DJ Shadow y todo su catálogo posterior marcó el fin de Mo’Wax.

¿Conocías el conflicto central en MoWax antes de hacer la película? Hablanos un poco sobre la naturaleza del mismo.

Era consciente del conflicto central en la vida de James. Pienso que el principal problema fue la forma que tenía de trabajar, por ciclos, volcándose en un mejor amigo como colaborador central creativo que que funcionaba como pieza clave durante un período de 5-7 años para luego termina de forma abrupta y trágica. Siempre supe que ese era el punto a explorar en la película. Ese problema fue recurrente a lo largo de la vida de James; con DJ Shadow, con Rich File, y con Pablo Clements. Siempre planeé construir la película siguiendo el tema clave de la amistad versus el éxito.

¿Te enfrentaste a este proyecto teniendo claro cómo iba a ser el comienzo y el final de la historia?

Absolutamente. De hecho, esperamos 3 años para nuestro final. No filmamos prácticamente nada del 2011 al 2014, esperando que la carrera de James proporcionara un final. Una vez se anunció que James iba a dirigir el Meltdown Music Festival reaccionamos subitamente porque sabíamos que eso nos proporcionaría la reconciliación con los viejos amigos que la película necesitaba. Siempre supe que quería que la película comenzara con un rápido ascenso a la fama y la fortuna. Siempre supe que la película en esencia era sobre la importancia de las amistades en la búsqueda del éxito.

¿Cambió mucho la historia durante el proceso de creación? ¿Te sorprendió el material de archivo con algo que no te esperaras y que te hiciera replantearte de alguna forma la historia?

No, siempre pensé que sería una historia sobre arte vs comercio, amistad vs éxito. Hubo, por supuesto, pequeñas sorpresas en el archivo; momentos divertidos, pequeñas historias, pero me mantuve firme en mi plan de hacer una historia trepidante, entretenida, ascendente y redentora. Una historia que abriera una ventana que mostrase a un montón de buenos artistas underground británicos a una audiencia más amplia, y a la vez contar la parte humana de la vida de James, cómo su implacable necesidad de crear arte impactó en su vida personal.

Cuéntanos un poco acerca de tu película documental favorita. Esa que más te influenció.

‘Joe Strummer: The Future is Unwritten’ es increíble. También me encanta ‘Anvil: The Story of Anvil’.

¿Tengo razón si digo que MoWax fue el mayor y último sello de influencia hip-hop que funcionó como una comunidad de músicos y artistas plásticos? (Sé que Ninja Tune también es una referencia, aunque no alcanzaron un éxito tan grande como Mo’Wax con el Endtroducing de Dj Shadow)

Ninja Tune eran grandes rivales de Mo’Wax en ese momento. Mo’Wax tiene una historia más interesante, puntos altos más importantes, sin duda, pero el final Ninja Tune sobrevivió y ahí están hoy. Mo’Wax ya no existe. La escena de hip hop del Reino Unido está realmente dominada ahora por el Grime, en este momento hay una gran comunidad alrededor de esa música en el Reino Unido. Estoy seguro de que habrá grandes historias para futuros documentales en los próximos años.

¿Qué tres consejos darías a alguien que quiera embarcarse en un proyecto de película documental como esta?

- Asegúrate de tener acceso privilegiado y exclusivo al tema que vayas a tratar.

- Disposición a material nunca antes visto. Archivos perdidos.

- Si tu idea es proyectarlo en cines, piénsalo como una película. Estructúralo como una película. Móntalo como una película.

- Busca la emoción y el sentimiento. Los documentales largos tratan más sobre destilar la esencia de la verdad, y no tanto en ser esclavo de la cronología.

English:

THE MAN FROM MO’WAX

In the year ’92 a fresh underground record label came to light under the name of Mo’Wax. Focused on Trip-Hop, turntablism and alternative Hip Hop was intended to enrich an already prolific music scene when musical genres were mixed up in unthinkable idiosyncrasies if comparing with decade before. Thanks also to the proliferation of ‘home studios’ (which allowed the people to professional digital recordings) and a new trend of musical composition based on collage, such as the cut’n’paste, many musicians explored different paths that, mostly supported by electronics, generated the spearhead of urban avant music.

Founded by two young djs, James Lavelle and Tim Goldsworthy, Mo’Wax set out not only for a mere mercantilist purpose, but also embraced the idea of creating a community around, a community of people linked to the streets and the art; a philosophy that was not common until then.

In ’96 Mo’Wax released the album Endtroducing by Dj Shadow, an album that generated an unexpected success, and catapulted the label to the top, converting James Lavelle (main responsible for the meteoric success) in a key figure in the world scene. Years later, disagreements on a personal and financial level truncated the continuity of the label, plunging James Lavelle into a situation in which he lost his entire catalog of artists.

The story of Mo’Wax and James Lavelle is a story of success and failure that filmmaker Matthew Jones presents to us in his new documentary ‘The Man From Mo’Wax’. The director, has had access to a large amount of archival material that has never been seen before. With all this he has built a complete history of the Mo’Wax universe, that moment musical scene and its key man James Lavelle.

We were talking to the director about the film and he answered several questions.

To our readers that did not watch the film yet: What is “The Man From Mo’Wax” about? (beside music of course) Friendship, ambition, success, failure, love…

You said it. It’s about the phenomenal rise and redemption of James Lavelle. It’s about the friendships you lose when you pursue career success at any costs. How do you follow up on a hugely successful record? How do you recreate success and reinvent yourself? Is it worth it if your relationships fall apart? It’s a celebration of Mo’Wax music, but more importantly a poignant examination of the power of friendship.

What was your seminal inspiration for making this film?

I was inspired by James’ entrepreneurial attitude, his never say die outlook. I was fascinated by the Mo’Wax record label – its history, and the whole visual identity and culture James built around his iconic London Label.

Did Lavelle watch the film? Is he happy?

Yes, he’s seen it many times. I think he’s cool with it. Seeing your biggest mistakes play out on screen is hard for anyone. I don’t know if I could cope with a film like this about me, so the fact James is supporting the film’s release, doing appearances, DJ Sets and Q&As I really respect and thank him for. He told us it’s really well put together and I think he finds the film very cathartic. It has given him some perspective on his mistakes and it has also rekindled some of his old friendships which is great.

A big amount of the material used for making this film came from Lavelle’s own archive. Some of the footage looks pretty intimate. Did James want to control in any way any part in the creation of the film?

Of course, James was involved. He’s an active artist and the film was important to him. At the same time, I made the film I wanted to make and did not allow James to dictate anything about the structure or direction of it. We said from day one we wanted to make a honest ‘warts and all’ documentary. It could not be sycophantic, there are so many vacuous concert driven, ‘look at me I’m amazing’ documentaries made by the music industry that are basically 2 hour commercials. It’s such a waste of time. We showed James rough cuts of the film, and he would offer feedback – some of that was really valuable – contacts for people we had not yet interviewed and additional photographic archive to help paint the picture. Other feedback we pushed back on. James disliked the Where Did The Nightfall section a lot. He wanted those changed, but I was there throughout the creation of that 4th record and it was depressing, it was a mess, there was no energy. The collaborations had dried up, everything was being done with artists via the internet. It just lacked soul and direction to me and I think that came out in the record that was made, and the film reflects that. Yet it’s hard for anyone to see some of their biggest dreams not turn out the way they intended. Failure is part and parcel of the creative world. Most projects are not successful. James’ criticisms of the film are all about sections when things did not go well for him. It’s immeasurably tough seeing your mistakes pointed out on a cinema screen.

James Lavelle as an A&R, as a Rock Star, as a producer. In your opinion, was the mixing of these profiles the failure of MoWax?

The main reason Mo’Wax failed was the financing deal they had with A&M Records coming to an end in 1998. Mo’Wax became a pawn in the massive merger between Polygram (who owned A&M) and Seagram that gave birth to Universal Music as we know it today. I think Mo’Wax would have survived James wanting to be the artist had the A&M finance deal remained in place. The problem was he lost his artists to Island Records and James thinks really big so without that financing behind him he can’t back records the way he wants to. Ultimately losing the security of Osman Eralp at A&M, then losing control of UNKLE, DJ Shadow and his back catalogue was the beginning of the end for Mo’Wax.

Were you aware about the central conflict in Mo’Wax before making the film? Tell us about the nature of it.

I was aware of the central conflict in James’ life, the main problem is the way he has a very cyclical nature of working with a best friend as a key central collaborator for a 5-7 year period and then it ends abruptly and tragically. I always thought that was the heart of the film. Exploring that problem that has recurred throughout James’ life; with DJ Shadow, Rich File and Pablo Clements. I always planned to build the film along that key theme of friendship vs success.

Did you face this project having a solid idea about the begining and the end of the story?

Absolutely. We actually waited for 3 years for our ending. We filmed nothing really in that period between 2011-2014, just waiting for James’ career to provide an ending. Once it was announced he was doing the Meltdown Music festival we pounced because we knew that would provide us with the reconciliation with old friends that the film needed. I always knew I wanted the film to start with a rapid rise to fame and fortune. I always knew the film at its core was about the importance of friendships over the pursuit of success.

Did the story change a lot during the process of creation? Did the archive material surprised to change any part of the story?

No, I always planned it to be a story about art vs commerce, friendship vs success. There were, of course, small surprises in archive – funny moments, little stories but I stuck to my plan of making a fast-paced, highly entertaining, rise-fall-redemption story. A story that would open up a really cool pocket of underground British music to a wider audience and told a human story of James’ life, how his relentless need to create art impacted his personal life.

Tell us a bit about your favourite music documentary film. The one that influenced you a lot.

‘Joe Strummer: The Future is Unwritten’ is incredible. I also LOVE ‘Anvil: The Story of Anvil.’

Am I right affirming that MoWax was the biggest and the last hip-hop oriented influence label that worked as a community of musicians and plastic artists? (I know Ninja Tune is also a reference although they didn’t achieve such a big success as Mo’Wax with Dj Shadow’s Entroducing)

Ninja Tune were big rivals to Mo’Wax at the time. Mo’Wax has a more interesting story, greater high points for sure, but in the grand scheme of things Ninja Tune survived and is still going today. Mo’Wax is no more. The UK Hip Hop scene right now is really dominated by Grime, there is a big community around that music in the UK right now. I’m sure there will be some great stories to come out of that scene in documentaries in years to come.

Name three Gold tips before embarking in a documentary film project like this.

- Make sure you have great (ideally exclusive) insider access to your subject.

- Unearth never before seen, lost archive.

- If you want it in cinemas, think of it like a film. Structure it like a movie.

- Go with emotion and feeling. Feature length docs are about distilling out the essence of the truth, not being a slave to chronology.

www.themanfrommowax.com