Chris Dodge siempre estaba allí, siempre aparecía en mis discos favoritos de los 90 y todavía lo sigue haciendo con To the point y Marxbross. Persona clave en una escena que dio un nuevo enfoque al punk, volviéndolo más rápido y agresivo y ayudando a través de su sello a difundir ese nuevo sonido. Desde luego, alguien fundamental para entender la evolución de un movimiento tan maravillosamente poliédrico como es el punk.

Durante la primera ola de Powerviolence, Spazz y Slap & Ham fueron fundamentales en el desarrollo del género ¿qué grupos destacarías de ese momento?

Fuimos influenciados por las primeras bandas pioneras de hardcore como Deep Wound, Siege, Larm, Pandemonium, Neos, los primeros DRI … usamos esas influencias y las llevamos un paso más allá. Infest comenzó a tocar el estilo que finalmente se convirtió en el marco para el sonido Power Violence. Sin embargo, la “primera ola” de bandas Powerviolence no sonaba toda igual: Man Is The Bastard, Capitalist Casualties, No Comment, Crossed Out…, todos sonaban diferentes, pero todos éramos amigos con un interés compartido común en la música hardcore. Y esto fue principalmente único porque era un momento en el que solo el pop punk y el emo se consideraban aceptables en el mundo del punk.

¿Cómo fue la génesis de Spazz?

Estaba en una banda hardcore en los 80 llamada Stikky. Cuando Stikky dejó de tocar, tuve dificultades para encontrar otros músicos que quisieran tocar rápido. Como mencioné anteriormente, en ese momento la escena punk en el área de San Francisco tenía que ver con el emo y el pop punk. Nadie quería tocar hardcore. Leí una entrevista con Max Ward, el batería de Plutocracy, en una revista local llamada “Atmosphear” en enero de 1993. En la entrevista Max dijo que estaba comenzando una nueva banda con Dan Lactose, guitarrista de Sheep Squeeze, y que estaban tocando solamente canciones cortas y rápidas, y no tenían bajista. Inmediatamente me puse en contacto con él y me invitó a unirme. Max y Dan ya tenían 10 canciones escritas. Me reuní con ellos y ensayamos una vez (las canciones eran muy simples), luego grabamos en el estudio. Utilicé ese material para lanzar el primer 7 ” de Spazz.

Volviendo a Slap A Ham, ¿qué fue lo que te motivó a poner en marcha un sello discográfico?

En la década de los ochenta, había muchas bandas geniales que descubrí a través de conciertos y shows en vivo, pero las bandas que me gustaban parecían no tener interés por las discográficas. No podía entender por qué ninguna los ayudaría. El enfoque inicial de mi sello era apoyar a las bandas que no parecían tener apoyo en ningún otro lado.

El ejemplo perfecto es Capitalist Casualties. Estuvieron sin discográfica 5 años antes de que lanzaran su primer 7 “. Hasta ese momento, ni un solo sello se les acercó para publicar un disco. Ni siquiera pudieron incluir una de sus canciones en un disco recopilatorio.

¿Cómo fue la recepción de un sonido tan extremo por el momento?

La recepción fue mixta. Hubo un pequeño núcleo de seguidores que entendieron por qué era genial y lo apoyaron. A finales de los 80 y principios de los 90, el clima de la escena punk era muy anti-hardcore, así que estábamos haciendo algo que no era popular en absoluto.

Creo que hiciste los carteles de Slap A Ham. ¿De dónde viene toda esa imagen de lucha libre y también el uso de tantas palabras en español?

Usamos muchas imágenes de lucha mexicana en los lanzamientos de Spazz porque pensamos que era divertido. Y ninguna otra banda estaba haciendo eso en sus lanzamientos. California tiene una gran población mexicana y una cultura muy arraigada, por lo que fue natural integrarla en nuestras canciones e imágenes.

También usé el nombre “La Fiesta Grande” para los shows anuales de Slap A Ham porque pensé que era divertido, solo porque uno esperaría que un espectáculo de powerviolence se llamara “Brutal Devastation Fest” o “Extreme Fastcore Extravaganza”. Llamarlo algo que sonase feliz no era muy típico de mi tonto sentido del humor.

Spazz, 1997

La Fiesta Grande se ha convertido en una referencia en el P.V. por su ayuda en la configuración de una escena, ¿cómo lo recuerdas? ¿Organizaste el festival tú solo?

El primer Fiesta Grande fue una sugerencia de mi amigo Ken Sanderson de Prank Records. Ken estaba contratando bandas en 924 Gilman y estaba organizando un espectáculo para Assuck. Me llamó y me dijo que debería invitar a todas las bandas del sello y convertirlo en una especie de escaparate. Entonces me puse en contacto con Man Is The Bastard, Capitalist Casualties, Crossed Out, No Comment, y Plutocracy. Eso fue Fiesta Grande # 1 en enero de 1993. Configuré un total de 7 espectáculos anuales Fiesta Grande. Los organicé yo mismo, pero no fui un promotor, en el sentido que piensas de un promotor … No tomé ningún dinero de la puerta, y no les prometí a las bandas ninguna garantía. Todas las bandas de fuera de la ciudad viajaron para tocar en Fiesta Grande usando su propio dinero porque estaban emocionadas por poder tocar. Gilman me permitió tener el club durante un fin de semana. Me ponía en contacto con las bandas que quería en la lista cada año, creaba el flyer, y personas de todo el mundo llegaban en el mismo fin de semana todos los años para celebrarlo. Era una reunión de personas de ideas afines que amaban el mismo estilo de música hardcore.

Ahora que este género es muy popular y hay mucho interés en los grupos de los 90, ¿sientes que de cierta manera están reclamando lo que hiciste?

Todos toman de una u otra manera la influencia del pasado. Todas las bandas originales de powerviolence tomaron elementos de bandas de hardcore anteriores y los hicieron más extremos. Las bandas de hoy toman elementos de las primeras bandas de powerviolence y los convierten en algo nuevo. Cuando escucho a una banda que suena como Spazz, me siento halagado de que a la gente todavía le importe lo que hicimos.

Estás involucrado en el punk desde principios de los 80, en todas las facetas posibles, ¿qué te mantiene vinculado a este género musical y a esta forma de trabajar (DIY)?

Siempre me ha encantado la idea de que cualquiera pudiera estar involucrado. No hay estrellas del rock. Cualquier cosa que quieras hacer, puedes hacerlo tú mismo. Cuando tenía 14 años envié algunas críticas a un pequeño fanzine y publicaron mis escritos. Escribí cosas para MaximumRockNRoll cuando tenía 16 y 18 años. Todo lo que tenía que hacer era hacer un pequeño esfuerzo para llegar y la comunidad DIY lo apoyaba. Eso fue lo más alentador para mí en los primeros años.

La mayoría de las personas “normales” en la sociedad común nunca creerían que existe esta extensa red de fanáticos incondicionales que permiten a las bandas viajar por el mundo, ¡aunque la mayoría de ellas son pobres!

Siempre me ha inspirado esta música y la gente, y todavía lo hace.

¿Cómo crees que las etiquetas funcionan ahora en comparación con cuando Slap A Ham estaba activo?

Creo que sería mucho más difícil montar un sello discográfico ahora. Cuando yo editaba discos, normalmente podía lanzar algo un mes después de tener listos los masters. En estos días, algunos de mis amigos que dirigen sellos me dicen que tienen que esperar de 4 a 5 meses.

Internet es bueno y malo … lo bueno es que puedes distribuir tu música al instante en todo el mundo, pero lo malo es que es más difícil destacar cuando TODOS en todo el mundo publican cosas nuevas todo el tiempo. Hay demasiadas cosas al mismo tiempo. Es sobrecarga de música. Pero si lo haces porque te encanta hacerlo, eso es lo único que realmente importa.

Spazz, 1995

Acabas de grabar el bajo en Marxbros con gente de Seein Red y Larm. ¿Cómo surgió esta colaboración?

Sí, estaba muy entusiasmado con eso … Cuando estaba en los Países Bajos a principios de 2016, me encontré con Paul y Olav y me contaron sobre algunas canciones nuevas que estaban escribiendo y de que no tenían un bajista. Les dije que si no podían encontrar a nadie, deberían enviarme las canciones y yo grabaría el bajo. No pensé que eso realmente sucedería, pero me contactaron unos 6 meses después y realmente funcionó. Mejor aún, volví a visitar a finales de 2017 y tocamos dos veces en directo. En Amsterdam nos encontramos en el club antes del show, ensayamos, y luego unas horas más tarde tocamos nuestro primer concierto.

Una cosa que siempre me he preguntado, ¿cuál es la relación de Kool Keith con Spazz?

Dan Lactose siempre ha sido un gran fanático del rap / hip hop, y era un gran fanático de Kool Keith. Nuestro amigo Neil Nordstrom, que escribió para MRR, vivía en un apartamento, y su casero era Dan The Automator. Descubrió que Dan The Automator estaba trabajando en San Francisco en el primer álbum de Dr. Octagon, por lo que Dan Lactose fue al estudio y conoció a Kool Keith. Kool Keith estaba hablando de cuánto le gustaba el thrash metal y Dan Lactose le contó sobre Spazz. A Keith le gustó, así que incluyó a Spazz en la letra de la canción “I’m Destructive”, y también grabó para nosotros en el álbum de Spazz “La Revancha”.

En este momento el vinilo vive en una especie de burbuja, ¿qué piensas de los altos precios que se pagan por los viejos discos de HC y punk? ¿No hay algo contradictorio?

No puedo creer los precios de algunos de esos viejos discos. Es una locura. No entiendo por qué las personas pagan tanto o cómo pueden pagarlo. Una de las pocas cosas que me gusta de internet y el intercambio de archivos en estos días, es que es posible encontrar la música que desea escuchar sin pagar $ 400 por un 7 “. Parece criminal, realmente.

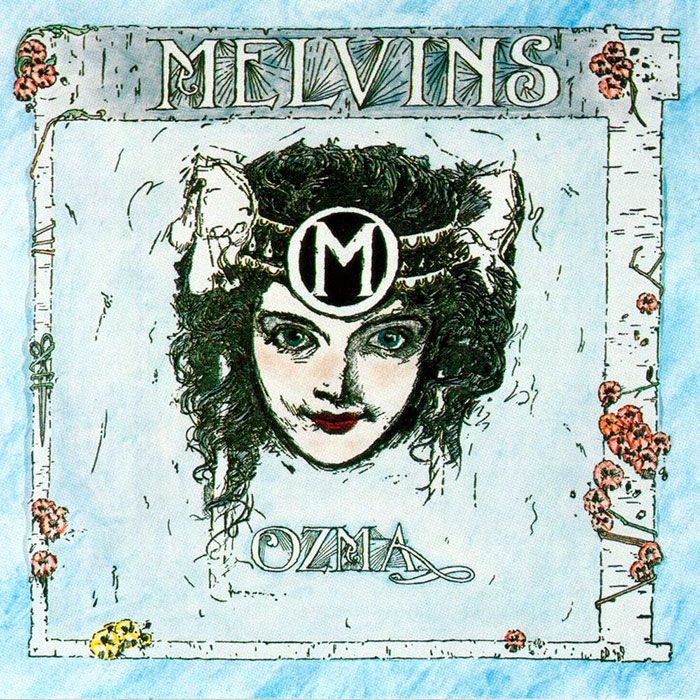

No conocía tu faceta como pintor. ¿Cómo surgió la colaboración para hacer la portada de Ozma de los Melvins?

Fui amigo íntimo de los Melvins cuando se mudaron a San Francisco alrededor de 1988. Antes había conocido a su bajista Lori Black cuando estaba en una banda punk llamada Clown Alley. Buzz y Dale no conocían a mucha gente en la ciudad, y pasamos mucho tiempo juntos. Estaban hablando de lo que querían para la portada de Ozma, y Lori tenía algunas ediciones antiguas (años 1930) de viejos libros de Oz, que tenían estos elaborados dibujos. Me ofrecí a intentar hacer la obra de arte, así que adapté un viejo dibujo del libro The Ozma Of Oz.

¿Qué tiene de especial la escena de L.A. con respecto a otros lugares?

Crecí en la escena de la bahía de San Francisco, pero luego me mudé a Los Ángeles en 2001. ¡La escena de Los Ángeles es mucho mejor! Mucho más amigable, mucho más solidaria y más fácil de manejar. Las personas involucradas están genuinamente entusiasmadas con lo que están haciendo. En los primeros días, cuando vivía en San Francisco, siempre pensé que LA era la mejor ciudad para tocar en Estados Unidos, y todavía lo pienso.

Don plaid retina, gg allin, chris dodge

English:

CHRIS DODGE: THE GENESIS OF A SOUND

Chris Dodge was always there, he always appeared on my favorite albums of the 90s and he still does it with To the point and Marxbross. Key person in a scene that gave a new focus to punk, making it faster and more aggressive and helping through its label to spread that new sound. Of course, someone fundamental to understand the evolution of a movement as wonderfully polyhedral as is punk.

During the first wave of Powerviolence Spazz and Slap & Ham were fundamental in the development of the genre, what groups would you highlight at that time?

We were influenced by the early pioneering bands of fast hardcore like Deep Wound, Siege, Larm, Pandemonium, Neos, early DRI… we used those influences and carried it a step further. Infest started playing the style that eventually became the framework for the Power Violence sound. But the “first wave” of power violence bands did not sound alike… Man Is The Bastard, Capitalist Casualties, No Comment, Crossed Out…. They all sounded different, but we were all friends with a common shared interest in aggressive hardcore music. And this was mainly unique because it was a time when only pop punk and early emo was considered acceptable in the punk world.

How was the genesis of Spazz?

I was in a fast hardcore band in the 80s called Stikky. When Stikky stopped playing, I had a difficult time finding other musicians who wanted to play fast. As mentioned above, at the time, the punk scene in the San Francisco area was all about emo and pop punk. Nobody wanted to play hardcore. I read an interview with Max Ward, the drummer for Plutocracy, in a local zine called “Atmosphear” in January 1993. In the interview Max said he was starting a new band with Dan Lactose, guitarist from Sheep Squeeze, and they were playing all short & fast songs, and they did not have a bass player. I immediately contacted him and invited myself to join. Max and Dan already had 10 songs written. I met with them and we practiced once (the songs were really simple), then we recorded in the studio. I used that material to release the first Spazz 7”.

Returning to Slap & Ham, what was it that motivated you to start up a label?

In the 80s there were so many great bands who I discovered through demo tapes and live shows, but the bands I liked seemed to have no interest from record labels. I could not understand why no labels would help them out. The initial focus of my label was to support bands who didn’t seem to have support anywhere else.

The perfect example is Capitalist Casualties. They were around for 5 years before I released their first 7”. Up until then, not a single label approached them to put out a record. They couldn’t even get one of their songs on a compilation record.

How was the reception of such an extreme sound for the time?

The reception was mixed. There were a small core of followers who understood why it was great & supported it. In the late 80s and early 90s, the climate of the punk scene was very anti-hardcore, so what we were doing what not popular at all.

I think you made the posters of Slap A Ham. Where does all that wrestling imagery come from and also the use so many words in Spanish?

We used a lot of Mexican wrestling imagery on Spazz releases because we thought it was funny. And no other bands were doing that on their releases. California has a large Mexican population & deep-rooted culture, so it was natural to integrate it into our songs & imagery.

The annual Slap A Ham shows I called “Fiesta Grande” also because I thought it was funny, only because you would expect a power violence show to be called something like “Brutal Devastation Fest” or “Extreme Fastcore Extravaganza”. Calling it something that sounded happy was pretty typical for my dumb sense of humor.

La Fiesta Grande has become a reference in the P.V. for its help in shaping a scene, how do you remember that time? Did you organize the festival by yourself?

The first Fiesta Grande was a suggestion by my friend Ken Sanderson from Prank Records. Ken was booking bands at 924 Gilman and was setting up a show for Assuck. He called me and said I should invite all of the bands on the label and make it a showcase of sorts. So I contacted Man Is The Bastard, Capitalist Casualties, Crossed Out, No Comment, and Plutocracy. That was Fiesta Grande #1 in January 1993. I set up a total of 7 annual Fiesta Grande shows. I organized them myself, but I wasn’t a promoter, in the sense that you think of a promoter… I didn’t take any money from the door, and I didn’t promise the bands any guarantee. All of the bands from out of town traveled to play Fiesta Grande using their own money because they were excited to play. Gilman allowed me to take over the club for a weekend. I contacted the bands who I wanted on the bill each year, I created the flyer, and people from all over the world arrived on the same weekend every year to celebrate… it was a gathering of like-minded people who all loved the same style of extreme hardcore music.

Now that this genre is very popular and there is a lot of interest in the groups of the 90s, do you feel that in a certain way they are claiming what you did?

Everyone takes some form of influence from the past. All of the original power violence bands took elements of earlier hardcore bands and made the sounds more extreme. The bands of today take elements of the early power violence bands and modify them to something new. When I hear a band that sounds like Spazz, I’m flattered that people still care about what we did.

You are involved in punk since the early 80’s, in all possible facets, what keeps you linked to this musical genre and this way of working (DIY)?

I always loved the idea that anyone can be involved. No rock stars. Anything you want to do, you can do yourself. When I was 14 I sent some record reviews to a small fanzine and they published my writing. I wrote things for MaximumRockNRoll when I was 16 and 18. All I had to do was make a small effort to reach out & the DIY community supported it. That was the most encouraging thing for me in the early years.

Most “normal” people in regular society would never believe there is this extensive network of hardcore fans that enable bands to travel the world, even though most of them are poor!

I have always been inspired this music & the people, and I still am.

How do you think labels work now compared to when Slap & Ham was active?

I think it would be much more difficult to run a record label now. When I was pressing records, I could usually release something one month after I had the masters ready. These days some of my friends who run labels tell me they have to wait 4-5 months to get the pressing plants to make their records.

The internet is both good and bad… the good part is you can instantly distribute your music all over the world, but the bad part is it’s more difficult to be noticed when EVERYBODY all over the world is posting new stuff all the time. There is too much out there at the same time. It’s music overload. But if you do it because you love to do it, that is the only thing that really matters.

You just recorded the bass in Marxbros with people from Seein Red and Larm, how did this collaboration come about

Yes, I was very excited about that… When I was in the Netherlands in early 2016, I met up with Paul and Olav and they were telling me about some new songs they were writing, and how they didn’t have a bass player. I told them if they could not find anybody, they should send me the songs and I would record bass. I didn’t think that would actually happen, but they contacted me about 6 months later and it actually worked. Even better, I went over again in later 2017 and we played two live shows. In Amsterdam we met up at the club before the show, practiced, and then a few hours later played our first show.

One thing I’ve always wondered, what is Kool Keith’s relationship with Spazz?

Dan Lactose has always been a huge rap / hip hop fan, and was a big fan of Kool Keith. Our friend Neil Nordstrom, who wrote for MRR, lived in an apartment, and his landlord was Dan The Automator. He found out Dan The Automator was working in San Francisco on the first Dr. Octagon album, so Dan Lactose went to the studio & met Kool Keith. Kool Keith was talking about how much he liked thrash metal and Dan Lactose told him about Spazz. Keith was into it, so he included Spazz in the lyrics on the song “I’m Destructive”, and also recorded a shout out for us, which is on the Spazz “La Revancha” album.

Right now the vinyl lives in a kind of bubble, what do you think about the high prices that come to be paid for the old HC and punk records? Is not something contradictory?

I can’t believe the prices for some of those old records. It’s insane. I don’t understand why people pay that much, or how they can afford it. One of the few things I like about the internet and file-sharing these days, is it’s actually possible to find the music you want to hear without paying $400 for a 7”. It seems criminal, really.

I did not know your facet as a painter. How did the collaboration to make the cover of Ozma de los Melvins come about?

I was close friends with the Melvins when they first moved to San Francisco around 1988. I previously had known their bass player Lori Black when she was in an earlier punk band called Clown Alley. Buzz and Dale didn’t know many people in town, and we hung out a lot for a couple years. They were talking about what they wanted for the Ozma cover art and Lori had some vintage (1930s) editions of old Oz books, that had these elaborate drawings. I offered to try doing the artwork, so I adapted an old drawing from The Ozma Of Oz book.

What is special about the L.A. scene regarding other places?

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area scene, but then moved to Los Angeles in 2001. The LA scene is much better! Much friendlier, much more supportive, more easy-going. The people involved are genuinely excited about what they are doing. In the early days, when I lived in SF, I always thought LA was the best city to play in the US, and I still do.