(english below) En esta entrevista, exploramos la evolución artística de 108, desde sus inicios pintando en espacios urbanos hasta su consolidación en galerías y estudios. Nos habla sobre su relación con el color negro, su transición a la creación de instalaciones y esculturas en 3D, y cómo su vida personal, incluyendo la ansiedad, influye en su proceso creativo. Además, reflexiona sobre la evolución del arte urbano en Europa y su propia postura frente a esta corriente. A través de su perspectiva, descubrimos un artista comprometido con su libertad creativa y una visión introspectiva del arte.

¿Qué te inspiró a pasar de las letras tradicionales del grafiti a las formas abstractas?

Empecé alrededor del ’91 con algunos tags tempranos, y a mediados o finales de los ’90, el grafiti se convirtió en una de mis principales actividades. Al mismo tiempo, estaba profundamente inmerso en la música punk hardcore, el skate, los cómics y los fanzines underground. Nadie en mi familia era artista; mis padres eran trabajadores ferroviarios. Sin embargo, mi madre y mi abuelo tenían un gran interés por diversas formas de arte y cosas poco convencionales. En mi pequeña ciudad, formaba parte de un grupo de amigos muy unidos que compartían una pasión por el skateboarding. Descubrimos el grafiti a través de revistas de skate y los squats locales. Al principio, aspiraba a crear letras clásicas al estilo de Nueva York, Francia o Alemania, pero después de algunos años, me fascinó uno de los nuevos estilos europeos.

En el ’97, me fui de la casa de mi familia y me mudé a Milán con un amigo para estudiar en el Politécnico. Mis inspiraciones eran vastas. Continué haciendo grafiti tradicional mientras me cautivaban las pinturas murales tardías de Miró, los textos de Kandinsky y Malevich, y las obras de Jean Arp. También me influenciaron las portadas DIY del punk hardcore, los fanzines, el arte prehistórico y el ruido de Luigi Russolo. Me di cuenta de que haber nacido en una pequeña ciudad cerca de los Alpes occidentales significaba que mi entorno y cultura eran distintos, y quería crear algo original y único. Los logotipos abstractos en negro de Stak me inspiraron a creer que era posible hacer algo diferente y original en los espacios públicos. ¡Fue como un momento mágico!

¿Por qué elegiste el número 108 como tu pseudónimo artístico y qué significa para ti?

Cuando me mudé a Milán en el ’97, fue tanto emocionante como intimidante. Tenía 19 años y vivía en un mundo paralelo, explorando nuevas ideas y culturas con mi amigo. Estábamos muy metidos en el punk hardcore, y después de un verano de resacas extremas en Barcelona, decidí adoptar un estilo de vida straight edge, habiéndome hecho vegetariano dos años antes. Sin embargo, estaba luchando mentalmente.

En Milán conocí a algunos monjes Hare Krishna y, de vez en cuando, visitaba su restaurante vegetariano, algo bastante raro en esa época. Esto despertó mi interés por el hinduismo. Leí el Bhagavad Gita y comencé a usar un mala con 108 cuentas. Este periodo de mi vida coincidió perfectamente con mi creciente incomodidad con las actitudes egocéntricas en el grafiti y en la vida en general. Quería enfrentar mi ego, por lo que decidí cambiar mi nombre artístico. Usar un número en lugar de un nombre real me pareció innovador y me ofrecía una forma de distanciarme de mi ego. Así que elegí 108 para firmar mis trabajos, que en ese momento consistían en experimentos rudimentarios con formas abstractas y sonido. Con los años, he descubierto muchos significados asociados a este número. Sigo siendo vegetariano (casi vegano), ya no soy straight edge y sigo explorando el hinduismo, el budismo y más allá.

¿Cómo influyó tu formación en diseño en la Universidad Politécnica de Milán en tu enfoque artístico actual?

El aspecto más significativo de asistir a la universidad fue la transición de una pequeña ciudad a una metrópolis bulliciosa, así como dejar la casa de mis padres. No me gustaba mucho lo que estudiaba y a menudo luchaba con el estilo de vida universitario. Mientras otros salían de fiesta, yo, siendo straight edge, pasaba mi tiempo pintando paredes, asistiendo a conciertos o patinando. Perdí algunos años debido a mis dificultades con las matemáticas, pero también descubrí las obras, ideas y escritos de grandes artistas como Kandinsky, Klee y Olga Rozanova. Incluso hice un examen de Inteligencia Artificial hace 25 años, además de varios cursos de diseño, uno de semiótica y mi favorito, antropología cultural. Aunque en ese momento encontré estos textos desafiantes, ahora reconozco lo valiosos que fueron para formar quién soy y lo que hago.

¿Cómo impactaron los espacios abandonados en Alessandria en el desarrollo de tu estilo visual?

Este es un tema crucial para mí. Alessandria, una pequeña ciudad que ahora parece casi desprovista de vida, fue en su momento un importante centro industrial y militar en el norte de Italia hasta la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Cuando era niño, todavía podía sentir los vestigios de esa atmósfera. Mientras las instituciones culturales oficiales eran inexistentes, descubrí mis bandas, películas y libros internacionales favoritos en squats y eventos independientes. Muchas industrias locales y sitios militares fueron abandonados en los años 80 y 90, lo que creó un amplio espacio para la exploración, la pintura y otras actividades no convencionales. Hoy en día, la mayoría de esos espacios han sido destruidos, y ese mundo ha desaparecido en gran medida, aunque algunas personas continúan creando trabajos interesantes.

¿Qué papel juega la espiritualidad en tu trabajo, particularmente en la elección de números y formas?

Explicar la espiritualidad requeriría un libro entero, al igual que el término “magia”, que uso a menudo pero que quizá no comprenda del todo. El arte es profundamente importante para mí y para el mundo por muchas razones. Si vemos el arte solo de forma material, parece inútil; la música y la pintura no sirven para propósitos funcionales. Hoy en día, muchos ven el arte como algo que debe ser político o una herramienta de marketing para tener significado, pero creo que necesitamos lo “inútil” para enriquecer nuestras vidas. Los números son un ejemplo: a menudo los vemos como simples herramientas, pero conceptos como el cero y el infinito son profundamente significativos. Frecuentemente uso proporciones pitagóricas en mi trabajo, no solo como herramientas matemáticas, sino también como símbolos. Esto ilustra mi punto: intentar explicar el arte visual (o la música o la poesía) con palabras racionales es insuficiente. Si eso fuera posible, no necesitaríamos el arte en absoluto.

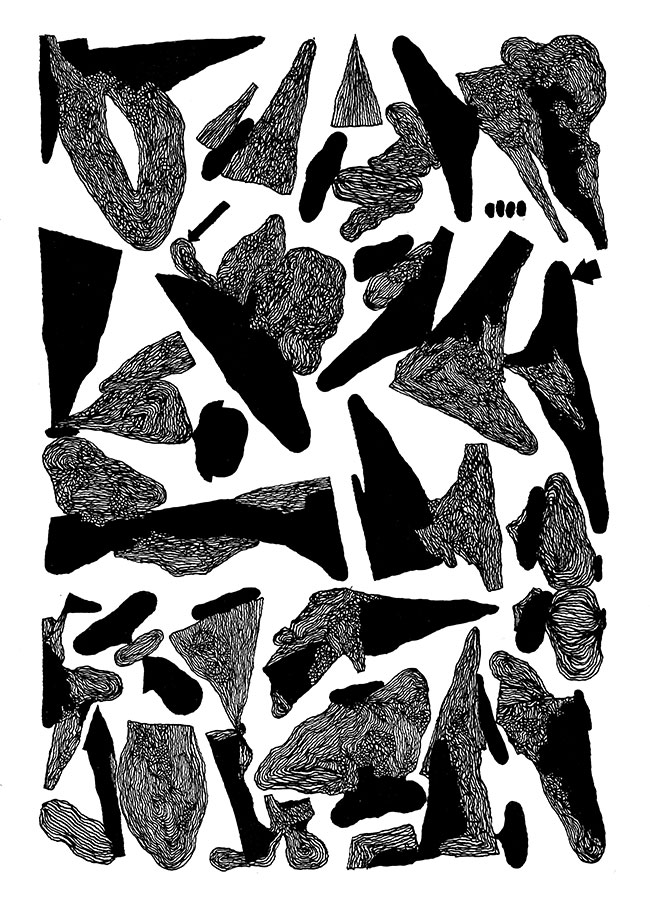

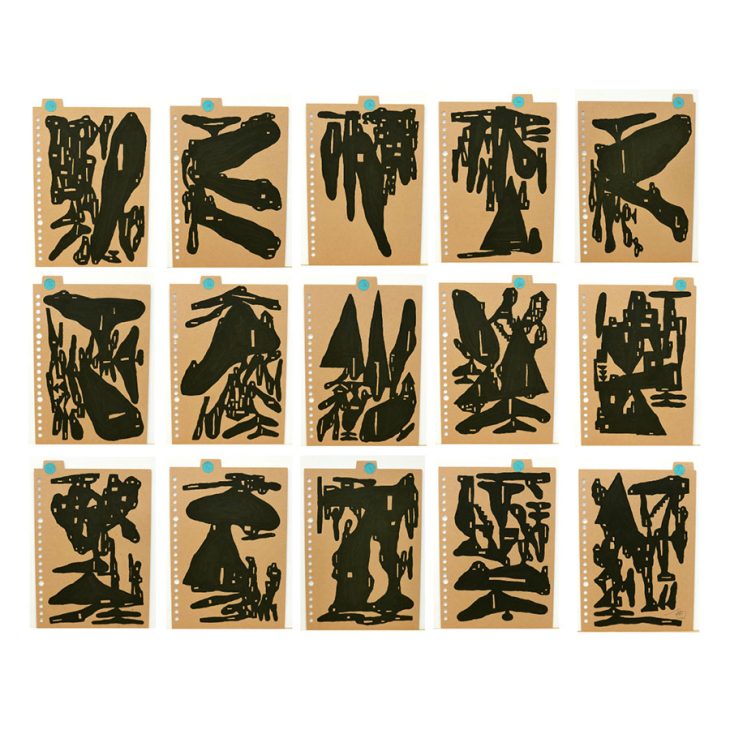

¿Cómo ha evolucionado tu estilo a lo largo de los años, desde el uso de figuras geométricas hasta formas más libres y orgánicas?

Mis primeras formas eran completamente libres y aleatorias, sin reglas. Luego evolucionaron hacia formas negras orgánicas, seguidas por años de trabajo con figuras geométricas negras, como círculos, triángulos y cuadrados, intercalados con colores orgánicos. Recientemente, he vuelto a las formas orgánicas, centrándome en la descomposición de las formas y experimentando con la armonía de diferentes líneas, texturas e imperfecciones. Aunque me atrae el minimalismo, actualmente disfruto del proceso de exploración. Mi trabajo refleja mis sentimientos en el momento, revelando a menudo un contraste entre mis lados racional e irracional.

¿Por qué te atrae el color negro y cómo influye en el simbolismo de tu obra?

Esta pregunta merece una exploración extensa, pero resumiré dos razones principales. Primero, el negro es el color perfecto para mis formas. Desarrollé mi estilo actual a principios de los 2000 en espacios abandonados, donde necesitaba algo rápido y poderoso. Siento que los colores pueden parecer poco elegantes y hasta irrespetuosos en esos entornos; el negro se siente más natural. Además, tiene profundidad: a veces parece una entrada, en lugar de una forma sólida.

Simbólicamente, el negro inicialmente representaba mi deseo de ser diferente. En ese momento, era uno de los pocos que utilizaban formas abstractas negras, principalmente en contextos ilegales, mientras que la mayoría se enfocaba en piezas coloridas y figurativas. A menudo usaba negro líquido con rodillos y pinceles grandes, creando obras crudas durante un período más oscuro de mi vida. También vestía de negro, y aunque esa etapa fue desafiante mentalmente, creo que algunas de mis mejores piezas surgieron de ahí. Hoy, veo el negro como un símbolo de lo desconocido, la introspección y la introversión.

¿Cómo equilibras la libertad creativa con la estructura geométrica en tus composiciones?

Este equilibrio surge casi de forma automática. Normalmente, comienzo con una forma principal, luego incorporo líneas rectas antes de agregar formas más orgánicas. Mis composiciones suelen involucrar varias capas. A veces empiezo con una estructura, utilizando proporciones como la regla de oro o dividiendo la superficie con números como el tres. En última instancia, depende de la pieza.

¿Cuáles son las principales influencias filosóficas detrás de tu trabajo, como el uso de símbolos y números?

No estoy seguro de que haya una filosofía claramente definida que guíe mi uso de símbolos y números. A veces anoto pensamientos o notas en mis pinturas, reflexiones que tengo durante el proceso creativo. También me gusta ocultar mensajes que pueden parecer algo extraños. Para mí, crear una pintura es como componer una canción; la música es inherentemente abstracta, aunque pueda estar acompañada de letras y ser cantada. Aprecio la ambigüedad porque la vida misma es a menudo incierta, y siempre me han atraído los misterios, como los que se encuentran en las tradiciones eleusinas.

En cuanto a los números, a veces los utilizo como notas sobre proporciones o repeticiones. Me ayudan a crear efectos visuales, y en otras ocasiones, simplemente son números sin un significado más profundo.

¿Cómo cambió tu enfoque artístico después de participar en exposiciones internacionales como la Bienal de Venecia y otras en Europa y EE.UU.?

Para ser honesto, no cambió mucho. Mi experiencia en el Arsenale de Venecia en 2007 fue significativa, pero casi me parece prehistoria. No tenía experiencia trabajando en un espacio así, y estaba completamente solo, incluso luchando para mover los grandes y pesados paneles. ¡Fue una pesadilla! Una vez que terminé, volé a Zaragoza para reunirme con amigos de Asalto, perdiéndome la inauguración en Venecia. A menudo me siento incómodo en lo que llaman situaciones “buenas”; he viajado solo tanto a eventos pequeños como a grandes exposiciones. El mayor cambio desde entonces es que me he vuelto más profesional con la edad, pero también me he hecho mayor, y ahora necesito un lugar cómodo para dormir y más tiempo para recuperarme.

¿Cómo fue la transición de pintar murales en las calles a trabajar con instalaciones 3D y esculturas?

No hubo una verdadera transición; siempre he trabajado en ambas áreas, junto con el sonido también. Sin embargo, crear esculturas e instalaciones requiere más tiempo y recursos. En mi mente, muchas de mis pinturas podrían fácilmente traducirse a formas tridimensionales.

¿Cómo influye tu vida personal, como lidiar con la ansiedad, en tu proceso creativo?

Es un poco extraño porque realmente necesito trabajar—me cuesta relajarme y siempre estoy pensando en mi próximo proyecto. Si no estoy pintando, estoy construyendo algo, preparando cintas o CDs, o reparando bicicletas. La única forma en que realmente desconecto es haciendo senderismo en las montañas, aunque lo he hecho menos en los últimos años. He intentado meditar y practicar la relajación, pero no ha sido fácil. Durante el confinamiento, finalmente encontré tiempo para meditar, lo cual fue genial. Comencé a hacerlo casi a diario, al menos 20 minutos, y ayudó significativamente, especialmente después de algunos años difíciles. Sin embargo, este verano tuve un incidente que hizo difícil la actividad física, así que quizás usé eso como excusa para parar. Me parece curioso decir que necesito pintar, pero cuando lo hago, a menudo no me siento relajado. Se siente como una lucha. Hago todo yo mismo, desde pintar hasta hacer los marcos y trabajar la madera, pero a menudo siento que estoy cerca de mis límites. Generalmente estoy apurado, sintiéndome agotado tanto mental como físicamente, lo que puede llevar a la confusión. Tal vez lo notes en mis obras recientes; parecen menos simples y más caóticas, algo reflejado en sus títulos. Encontrar el equilibrio se ha vuelto cada vez más difícil.

¿Qué importancia tienen los errores e imperfecciones en tus obras, y por qué decidiste incorporarlos en lugar de ocultarlos?

Desarrollé una apreciación por las imperfecciones en la última década. Siempre me han gustado las obras crudas, pero mi perspectiva ha evolucionado. Hace años, mientras hacía impresiones, noté que el impresor prefería copias perfectas, mientras que a mí me atraían más las que tenían fallos. Disfruto de esas imperfecciones “industriales”. Mi ansiedad también ha jugado un papel; a menudo he luchado con la certeza en cuanto a formas, líneas y colores, lo que añadía estrés a mi proceso. Comencé a aceptar correcciones visibles y permití que diferentes líneas coexistieran en la misma pieza, lo que hizo que las pinturas fueran más ricas e interesantes.

¿Cómo se compara la experiencia de crear arte en espacios urbanos con trabajar en galerías?

Cuando empecé a usar el nombre 108, mi objetivo no era llevar el grafiti a las galerías, sino introducir un tipo de arte diferente en las calles. Estaba experimentando y creando porque me gustaba y era importante para mí. Mi experiencia pintando muros sin comisiones ni presupuesto tenía como objetivo crear algo absurdo y distintivo, y todavía trabajo en espacios abandonados en 2024. Las cosas cambiaron a mediados de los 2000 cuando empecé a recibir invitaciones para festivales, que principalmente ofrecían viajes y alojamiento, pero sin mucha dirección artística. Hoy en día, aunque los presupuestos pueden ser mayores, los organizadores a menudo buscan arte decorativo, ilustraciones o diseño gráfico para las paredes. La calidad del trabajo ha mejorado significativamente, pero eso ya no es mi enfoque. Trabajar en mi estudio ahora se siente correcto; aunque me esfuerzo y experimento estrés, tengo la libertad de crear lo que quiero. Sé que no puedo cambiar mi enfoque para agradar a los demás, y he logrado mantener mi práctica durante muchos años.

¿Cómo ves la evolución del arte urbano en Europa desde que comenzaste hasta ahora, y dónde encaja tu trabajo dentro de este movimiento?

Honestamente, no estoy completamente seguro. Para mí, el apogeo del arte urbano fue a finales de los años 90 y principios de los 2000, cuando todo parecía posible y la gente no estaba tan enfocada en la fama o el dinero. Siempre me he sentido como un forastero, y probablemente todavía lo hago. Ciertamente, todavía hay grandes artistas creando en espacios públicos, incluidos algunos en mi área. El problema, creo yo, no es solo el arte urbano, es con todo ahora: solo existe lo mainstream y la mayoría de las personas quiere estar dentro. El underground parece estar muy, muy underground ahora… No lo sé. Es interesante ver que muchos artistas ahora están haciendo arte abstracto en negro, algunos de los cuales quizás ni siquiera conocen mi trabajo, lo que encuentro fascinante. Para responder a tu pregunta, no creo que mi trabajo encaje dentro del movimiento actual de arte urbano; me concentro más en mi práctica en el estudio, pintar en espacios abandonados, dibujar en mi cuaderno de bocetos mientras viajo, y experimentar con el sonido y la escultura.

English:

108. Artistic Creation in Complete Freedom

In this interview, we delve into 108’s artistic evolution, from his beginnings in urban spaces to his establishment in galleries and studios. He discusses his relationship with the color black, his transition to 3D installations and sculptures, and how his personal life, including anxiety, influences his creative process. Additionally, he reflects on the evolution of urban art in Europe and his stance on this movement. Through his perspective, we uncover an artist deeply committed to creative freedom and an introspective vision of art.

What inspired you to shift from traditional graffiti lettering to abstract forms?

I started around ’91 with some early tags, and by the mid to late ’90s, graffiti became one of my main activities. At the same time, I was deeply immersed in punk hardcore music, skateboarding, comics, and underground fanzines. No one in my family was an artist; my parents were railway workers. However, my mom and grandfather had a keen interest in various forms of art and unconventional things. In my small city, I was part of a close-knit group of kids who shared a passion for skateboarding. We discovered graffiti through skate magazines and local squats. Initially, I aspired to create classic New York, French, or German lettering, but after a few years, I became fascinated with some of the new European styles.

In ’97, I left my family home and moved to Milan with a friend to study at the Polytechnic University. My inspirations were vast. I continued creating traditional graffiti while also being captivated by the late wall paintings of Miró, the texts of Kandinsky and Malevich, and the works of Jean Arp. I was also influenced by the DIY hardcore punk cover art and fanzines, as well as prehistoric art and the noise by Luigi Russolo. I realized that being born in a small city near the western Alps meant my environment and culture were distinct, and I wanted to create something original and uniquely mine. The abstract black logos by Stak inspired me to believe that it was possible to do something different yet original in public spaces. It felt like a magical moment!

Why did you choose the number 108 as your artistic pseudonym, and what does it mean to you?

When I moved to Milan in ’97, it was both exciting and daunting. I was 19 and living in a parallel world, exploring new ideas and cultures with my friend. We were heavily into hardcore punk, and after a summer of extreme hangovers in Barcelona, I decided to adopt a straight edge lifestyle, having already become a vegetarian two years earlier. However, I was struggling mentally.

In Milan, I met some Hare Krishna monks and occasionally visited their vegetarian restaurant, which was quite rare at the time. This sparked my interest in Hinduism. I read the Bhagavad Gita and began wearing a mala with 108 beads. This period in my life aligned perfectly with my growing discomfort with the egocentric attitudes in graffiti and life in general. I wanted to confront my ego, which is why I decided to change my artistic name. Using a number instead of a real name felt innovative and offered a way to distance myself from my ego. Thus, I chose 108 to sign my work, which at that time consisted of rudimentary experiments with abstract forms and sound. Over the years, I’ve discovered many meanings associated with this number. I’m still a vegetarian (mostly vegan), I no longer straight edge, and I continue to explore Hinduism, Buddhism, and beyond.

How did your design education at the Polytechnic University of Milan influence your current artistic approach?

The most significant aspect of attending the university was the transition from a small city to a bustling metropolis, as well as leaving my parents’ home. I wasn’t fond of most of what I studied there and often struggled with the university lifestyle. As a straight edge, while others partied, I spent my time painting walls, attending shows, or skating. I lost some years due to my difficulty with math, but I also discovered the works, ideas, and writings of great artists like Kandinsky, Klee, and Olga Rozanova. I even took an exam in Artificial Intelligence 25 years ago, along with various design courses, one in semiotics, and my favorite in cultural anthropology. While I found studying these texts challenging at the time, I now recognize how valuable they were in shaping who I am and what I do.

How did the abandoned spaces in Alessandria impact the development of your visual style?

This is a crucial topic for me. Alessandria, a small city that feels almost lifeless now, was once a major industrial and military center in northern Italy until World War II. As a kid, I could still sense remnants of that atmosphere. While official cultural institutions were nonexistent, I discovered my favorite international bands, films, and books in squats and independent events. Many local industries and military sites were abandoned in the ’80s and ’90s, creating ample space for exploration, painting, and other unconventional activities. Today, most of those spaces have been destroyed, and that world has largely vanished, but some individuals continue to create interesting work.

What role does spirituality play in your work, particularly in the choice of numbers and forms?

Explaining spirituality would require an entire book, much like the term “magic,” which I often use but might not fully grasp. Art is profoundly important to me and the world for many reasons. If we view art purely materially, it seems useless; music and painting don’t serve functional purposes. Many today see art as needing to be political or a marketing tool to have meaning, but I believe we need the “useless” to enrich our lives. Numbers serve as an example: we often view them as mere tools, yet concepts like zero and infinity are deeply profound. I frequently use Pythagorean proportions in my work, not just as mathematical tools but as symbols. This illustrates my point—attempting to explain visual art (or music or poetry) with rational words falls short. If that were possible, we wouldn’t need art at all.

How has your style evolved over the years, from using geometric figures to more free and organic shapes?

My early forms were entirely free and random, devoid of rules. They then evolved into organic black shapes, followed by years of working with black geometric figures—circles, triangles, and squares—interspersed with organic colors. Recently, I’ve returned to organic forms, focusing on the decomposition of shapes and experimenting with the harmony of different lines, textures, and imperfections. While I’m drawn to minimalism, I’m currently enjoying the exploration process. My work reflects my feelings at the moment, often revealing a contrast between my rational and irrational sides.

Why are you drawn to the color black, and how does it influence the symbolism in your artwork?

This question deserves extensive exploration, but I’ll summarize two main reasons. First, black is the perfect color for my forms. I developed my current style in the early 2000s in abandoned spaces, where I needed something quick and powerful. I feel that colors can look inelegant and disrespectful to those environments; black feels more natural. It also has depth—sometimes it feels like an entryway rather than a solid form.

Symbolically, black initially represented my desire to be different. At the time, I was one of the few using black abstract forms, primarily in illegal contexts, while most others focused on colorful, figurative pieces. I often used liquid black with rollers and large brushes, creating raw works during a darker period in my life. I was also wearing black clothing, and while that time was challenging mentally, I believe some of my best pieces emerged from it. Today, I see black as a symbol of the unknown, introspection, and introversion.

How do you balance creative freedom with geometric structure in your compositions?

This balance comes almost automatically. I typically start with a main shape, then incorporate straight lines before adding more organic forms. My compositions often involve multiple layers. Sometimes I begin with structure, employing proportions like the golden ratio or dividing the surface with numbers such as three. Ultimately, it depends on the piece.

What are the main philosophical influences behind your work, such as the use of symbols and numbers?

I’m not sure there’s a distinct philosophy guiding my use of symbols and numbers. Sometimes, I jot down thoughts or notes on my paintings—reflections I have during the creative process. I also enjoy hiding messages that may seem a bit strange. For me, creating a painting is akin to composing a song; music is inherently abstract, yet it can be accompanied by lyrics and sung. I appreciate ambiguity because life itself is often unclear, and I’ve always been drawn to mysteries, much like those found in Eleusinian traditions.

As for numbers, they sometimes serve as notes about proportions or repetitions. They help me create visual effects, and at other times, they’re simply numbers without deeper meaning.

How did your approach to art change after participating in international exhibitions like the Venice Biennale and others in Europe and the U.S.?

To be honest, not much changed. My experience at the Arsenale in Venice in 2007 was significant, but it felt almost like prehistory. I had no experience working in such a space, and I was completely on my own, even struggling to move the large, heavy panels. It was a nightmare! Once I finished, I flew to Zaragoza to meet friends from Asalto, missing the opening in Venice. I often feel uncomfortable in so-called “good” situations; I’ve traveled alone for both small events and major shows. The biggest change since then is that I’ve become more professional with age, but also became older and now I need a comfortable place to sleep and more time to recover.

How was the transition from painting murals on the streets to working with 3D installations and sculptures?

There was no real transition; I’ve always worked in both areas, alongside sound as well. However, creating sculptures and installations requires more time and resources. In my mind, many of my paintings could easily translate into 3D forms.

How does your personal life, such as dealing with anxiety, influence your creative process?

It’s a bit strange because I really need to work—I find it hard to relax and am constantly thinking about my next project. If I’m not painting, I’m building something, preparing tapes or CDs, or repairing bicycles. The only way I truly disconnect is by hiking in the mountains, though I’ve been doing that less in recent years. I’ve tried to meditate and practice relaxation, but it hasn’t been easy. During the lockdown, I finally found time for meditation, which was great. I started doing it almost daily for at least 20 minutes, and it helped significantly, especially after some tough years. However, this summer I faced an incident that made physical activity difficult, so perhaps I used that as an excuse to stop. I find it amusing to say that I need to paint, yet when I do, I’m often not relaxed. It feels like a struggle. I do everything myself, from painting to making frames and woodworking, but I often feel close to my limits. I’m usually in a hurry, feeling exhausted both mentally and physically, which can lead to confusion. You might notice this in my recent works; they seem less simple and more chaotic, reflected in their titles. Finding balance has become increasingly difficult.

What significance do mistakes and imperfections hold in your works, and why did you choose to incorporate them instead of hiding them?

I developed an appreciation for imperfections over the last decade. I’ve always liked raw works, but my perspective has evolved. Years ago, while making prints, I noticed that the printer favored perfect copies, while I was drawn to the flawed ones. I enjoy those “industrial” imperfections. My anxiety has also played a role; I’ve often struggled with certainty regarding forms, lines, and colors, which added distress to my process. I began to embrace visible corrections and allowed different lines within the same piece, making the paintings richer and more interesting.

How does the experience of creating art in urban spaces compare to working in galleries?

When I began using the name 108, my goal was not to bring graffiti into galleries but to introduce different art into the streets. I was experimenting and creating because I enjoyed it and it was important to me. My experience of painting walls without commission or budget aimed to create something absurd and distinct, and I still work in abandoned spaces in 2024. Things shifted in the mid-2000s when I started receiving invitations for festivals, which primarily offered travel and accommodation without much artistic direction. Nowadays, while budgets may be higher, organizers often seek decorative art, illustration, or graphic design for walls. The quality of work has improved significantly, but that’s not my focus anymore. Working in my studio now feels right; although I push myself and experience stress, I have the freedom to create as I wish. I know I can’t change my approach to please others, and I’ve been able to sustain my practice for many years now.

How do you view the evolution of urban art in Europe from when you started to the present, and where does your work fit within this movement?

Honestly, I’m not entirely sure. For me, the peak of urban art was in the late ’90s and early 2000s when anything felt possible, and people weren’t as focused on fame or profit. I’ve always felt like an outsider, and I probably still do. There are certainly still great artists creating in public spaces, including some in my area. The problem I think is not only about urban art, is about everything now: there is just the mainstream and most of the people want to be inside. Underground seems to be really really underground now… I don’t know. It’s interesting to see many artists now doing black abstract art, some of whom may not even know my work, which I find fascinating. To answer your question, I don’t think my work fits within the current urban art movement; I focus more on my studio practice, painting in abandoned spaces, drawing in my sketchbook while traveling, and experimenting with sound and sculpture.