{english below} Greg Gulbransen es fotoperiodista y fotógrafo documental. Su carrera se ha centrado en capturar imágenes de situaciones complejas y emocionalmente intensas, incluyendo temas relacionados con conflictos, crisis humanitarias y aspectos sociales. Con “Say Less” (Gost Books 2024 – more info), Greg Gulbransen ofrece una inmersión profunda capturando momentos significativos a través de su lente en el barrio del Bronx en Nueva York, donde durante tres años, Gulbransen fotografió a Malik, un líder de un grupo violento de las calles, los Crips. Malik fue disparado y quedó paralizado en 2018 por una bala de una pandilla rival, y como resultado, su mundo ahora se centra en su pequeño apartamento donde es cuidado por su familia y miembros de la pandilla.

Gulbransen, había estado fotografiando en el Bronx durante su tiempo libre y había llegado a conocer a algunos de los jóvenes locales. Comenzó a notar a muchos jóvenes en sillas de ruedas con lesiones en la columna vertebral y se sintió profesionalmente curioso. Le dijeron que todos habían sido disparados y esta curiosidad le llevó hasta Malik. Las imágenes en el libro están cuidadosamente seleccionadas para representar una variedad de temas y situaciones, desde la intimidad de momentos personales hasta la grandiosidad de escenarios más amplios. El trabajo de Gulbransen se caracteriza por su enfoque en la sutileza y el detalle, capturando instantes que invitan al espectador a reflexionar y a involucrarse emocionalmente. Say Less ofrece una experiencia reflexiva y evocadora que reafirma el poder de las imágenes para contar historias significativas.

Reverend Tinnie James preaching to Malik © Greg Gulbransen

Después de conocer las historias de muchas personas como Malik, ¿qué te llevó a fotografiarlo y centrarte en su vida tras el tiroteo?

Como médico y fotógrafo, me siento inclinado a seguir historias que aborden problemas de salud pública que los estadounidenses necesitan comprender mejor para implementar cambios en las políticas. Uso ambos lados de mi cerebro simultáneamente (ciencia y arte) para contar la misma historia.

Eyanna has always been Malik’s primary caregiver, advocate and protector. The emotional bond between mother and son is unshakeable © Greg Gulbransen

¿Cuál fue el mayor desafío al fotografiar a Malik y su entorno? ¿Hubo algún momento específico que te impactara profundamente?

Como sabrás, Estados Unidos enfrenta una crisis de violencia armada que resulta frustrante para todos nosotros. Hoy en día, la principal causa de muerte entre los jóvenes en América es la violencia armada, y la población más afectada son los jóvenes afroamericanos de barrios marginales involucrados en pandillas. Estas comunidades necesitan ser mejor comprendidas para desarrollar cambios de políticas que rompan este ciclo vicioso de violencia. Vi en la historia de Malik una manera perfecta de ilustrar esta crisis de salud pública.

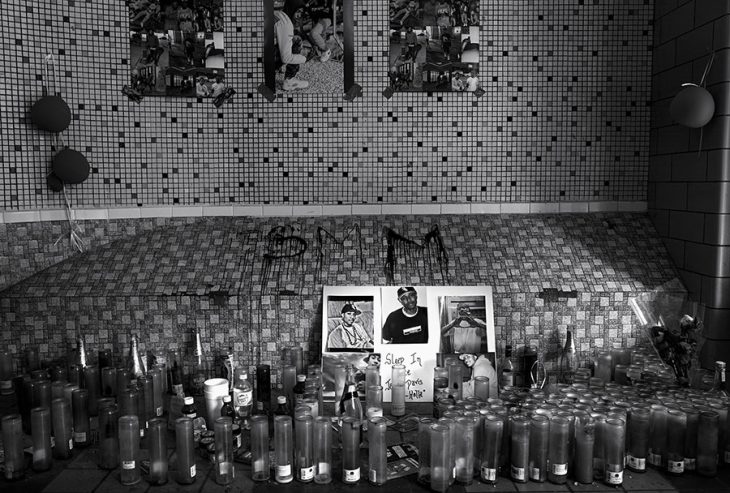

Makeshift memorial for Jay Holla, Malik’s friend who used to live in the Mitchel Houses

© Greg Gulbransen

¿Cómo reaccionaron Malik, su familia y los miembros de las pandillas a tu presencia y a las fotografías que tomaste? ¿Hubo reacciones inesperadas o significativas?

Hay una imagen de Malik en su silla de ruedas en un pasillo, mostrando los daños que causa a las paredes al moverse. Esto simboliza cómo, como víctima de violencia armada, Malik está atrapado, y también es una metáfora de cómo estos jóvenes de barrios marginales están atrapados en un mundo de violencia armada, al igual que TODO EL PAÍS está atrapado tratando de lidiar con esta crisis.

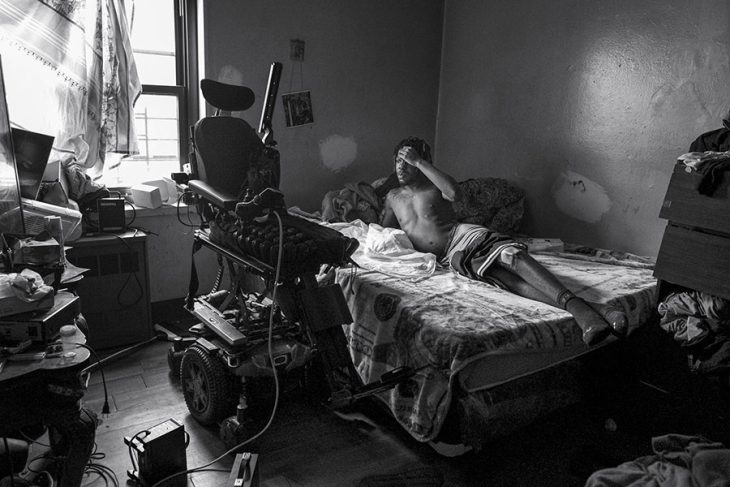

Malik’s bedroom in the Mitchel Houses. Malik spends most of his days in bed; his wheelchair is his only form of mobility © Greg Gulbransen

¿Qué esperas que los espectadores aprendan o comprendan a través de las fotografías en “Say Less”? ¿Hay algún mensaje específico que quieras transmitir?

Los desafíos fueron numerosos, incluyendo la logística de ir y venir desde mi casa a la ciudad, mi seguridad y la de mi equipo fotográfico, el acceso a ciertas personas que estaban con Malik en su habitación, y las largas esperas entre eventos importantes que ocurrían al azar, como apariciones en la corte o discusiones.

Malik being stripped down for his daily shower ©GregGulbransen

¿Qué impacto crees que tiene la violencia armada en la vida cotidiana de las personas en el Bronx, y cómo se refleja esto en tu trabajo?

Los momentos que más me conmovieron emocionalmente fueron cuando la familia y los amigos de Malik le cambiaban los pañales y lo cateterizaban. Esos siempre eran momentos tristes.

Tu trabajo se centra en la vida de alguien atrapado en un ciclo de violencia. ¿Cómo ves la relación entre la fotografía y el activismo al abordar problemas sociales como la violencia armada?

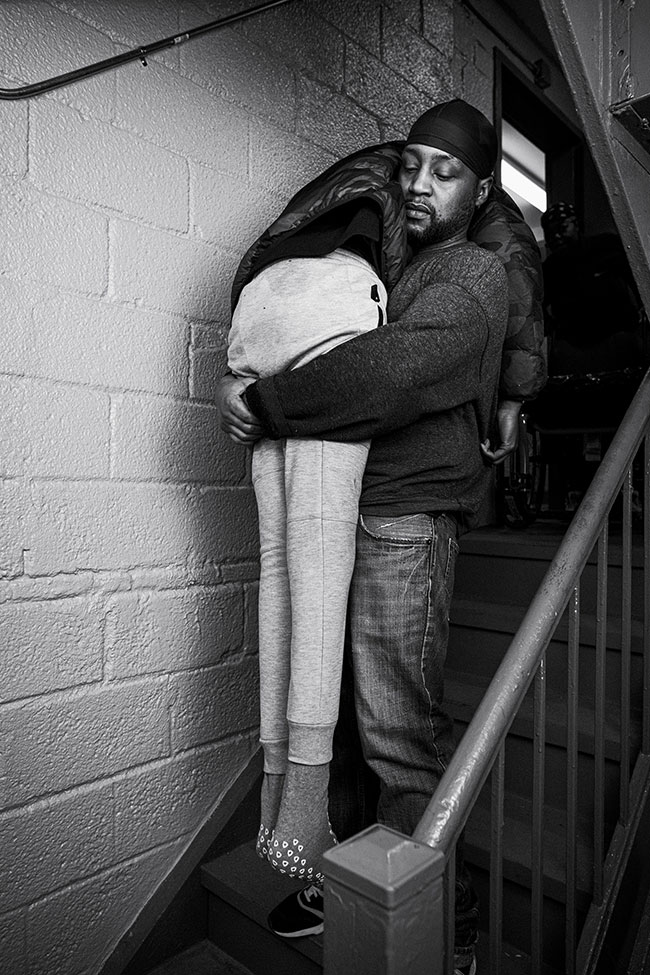

La familia de Malik y yo nos llevamos bien desde el principio porque fui muy amable con ellos, y querían que su historia fuera contada. Con el tiempo, nos acercamos aún más. Hubo ocasiones en las que los visitaba sin siquiera llevar mi equipo fotográfico.

‘I hate this gang shit,’ says Malik. ‘Everyday, I hope and pray that I am alive in the next five years.’ © Greg Gulbransen

¿Hay algo que hayas aprendido sobre ti mismo o sobre la fotografía documental mientras trabajabas en este proyecto?

Cualquier persona que se sintiera incómoda con mi cámara recibía todo mi respeto y nunca era fotografiada. No quería generar tensiones con estas personas en absoluto.

En tu trabajo fotográfico, has abordado temas complejos como la violencia armada y las consecuencias de las heridas por disparos. ¿Cómo integras tu conocimiento médico en la narrativa visual de tus proyectos para proporcionar una perspectiva más profunda y matizada sobre estos temas?

Mi objetivo era exponer el peligroso mundo de la violencia armada, específicamente en esta comunidad afroamericana de barrios marginales con pandillas y armas, y cómo estas personas nacen en este entorno. Están condenadas desde el principio. Los jóvenes negros tienen 17 veces más probabilidades de ser asesinados por un arma que sus contrapartes blancas de la misma edad. Este tema es muy complicado, y necesitamos comprenderlo mejor, sin estigmatizar a la comunidad.

Malikoncesaid;‘I’mrespectedbymanybuthatedbyall.’ ©GregGulbransen

Cuando trabajas con temas que intersectan la violencia y las experiencias personales en tus proyectos, ¿cómo evalúas el impacto de tu trabajo tanto en las comunidades que documentas como en el público en general?

Al principio, pensé que mi vida personal no formaba parte de la historia y que simplemente era un médico externo contando una importante historia de salud pública. No fue hasta mucho después, cuando enfrenté el trauma de haber matado accidentalmente a mi hijo de dos años en un accidente, que entendí que lidiar con esos demonios era el lugar desde el cual estaba dentro de la historia. Era la vida al borde de la muerte, y fue muy difícil. La cámara nos permite ver de cerca esos demonios y nos ayuda a enfrentarlos. La mayoría del buen arte involucra algún tipo de trauma.

La fotografía es extremadamente poderosa, como vemos diariamente en internet. Las personas prestan atención a las buenas imágenes, especialmente a una colección de imágenes que cuentan una historia importante. No sugeriría que este libro responde o soluciona problemas sociales, pero puedo decir que es el único libro fotográfico de su tipo. He regalado copias firmadas a muchos responsables de políticas en América, incluido el Cirujano General de los Estados Unidos, con la esperanza de abrir algunos ojos sobre este tema.

Manoeuvring his wheelchair in the narrow Hallway © Greg Gulbransen

No estoy seguro de si esto generará algún cambio social significativo, ya que muchos fotógrafos documentales famosos lo han intentado en el pasado (Eugene Richards, Eugene Smith, etc.). La fotografía es difícil de predecir, ya que el impacto de una imagen en particular puede no ser reconocido hasta muchos años después.

He aprendido que la fotografía documental es profunda y difícil. El fotógrafo debe dejar de lado sus ideas preconcebidas y prejuicios y contar la historia de la manera más objetiva posible. Ir despacio, escuchar, esperar, observar y ser respetuoso. Comprender el entorno y a las personas cuya historia estás contando. Pedir retroalimentación a lo largo del camino, tanto a personas internas como a amigos externos, para revisar tu trabajo. Fotografiar con profundidad y amplitud para capturar cosas que tal vez no percibas hasta después. Tomar descansos y regresar tantas veces como sea posible.

Este libro aborda muy bien las consecuencias de la violencia armada al contar la historia de Malik, quien quedó parapléjico tras recibir un disparo en la columna torácica y está confinado a la cama y a una silla de ruedas. También incluye a otras personas que luego recurrieron a las drogas para enfrentar las secuelas de sus heridas por disparos, así como al mejor amigo de Malik, quien fue herido en el abdomen y ahora vive con una bolsa de colostomía.

Phat Boy carries Malik down four flights of stairs © Greg Gulbransen

¿Crees que tu trabajo puede contribuir de manera constructiva a abrir debates sobre este tema y cuestionar los modelos sociales?

Mi conocimiento médico relacionado con esta historia comenzó cuando me preocupé por la cantidad de jóvenes en sillas de ruedas en esta parte del Bronx, algo que nunca había visto antes como médico. Me preguntaba: ¿cómo es que todos llegaron a estar tan discapacitados? Fue entonces cuando mi investigación me llevó a descubrir que muchas de estas personas eran víctimas de disparos. Con Malik, me centré en su atención médica, que incluía catéteres, cambios de pañales, infecciones renales que requerían hospitalización, cuidado de heridas y cambios de vendajes, entre otros. Habiendo cuidado pacientes discapacitados antes, comprendía estos problemas y me sentí cómodo usando la cámara durante estos momentos.

Es muy difícil medir objetivamente el impacto de mi trabajo en la comunidad y el público en general con esta historia. Mi objetivo ahora no es pasar a una nueva historia, sino permanecer con este tema para hablar públicamente sobre la violencia armada y cómo está matando a tantos jóvenes en América. Creo que esta historia es muy única y contribuirá a esta discusión en curso sobre esta emergencia de salud pública. “Say Less” es un libro fotográfico extremadamente diferente, ya que la historia que contiene, narrada por Bill Shapiro (Editor en Jefe, Life Magazine), es tan compleja como fascinante.

Reef assists Malik. A few weeks earlier, Reef had been on the lam after shooting and killing a man in Pennsylvania.

Days after this photo was made, Reef was arrested; he’s now serving two consecutive life sentences © Greg Gulbransen

The Mitchel Houses, in New York’s South Bronx © Greg Gulbransen

Typically, Malik’s only regular exercise is his daily morning pushup routine, which he does with his feet perched on the bed © Greg Gulbransen

English

SAY LESS: AN INTIMATE LOOK AT THE AFTERMATH OF VIOLENCE.

INTERVIEW WITH GREG GULBRANSEN

Greg Gulbransen is a photojournalist and documentary photographer. His career has focused on capturing images of complex and emotionally intense situations, including themes related to conflicts, humanitarian crises, and social issues. With “Say Less” (Gost Books 2024), Greg Gulbransen offers a deep dive capturing significant moments through his lens in the Bronx neighborhood of New York, where, for three years, Gulbransen photographed Malik, a leader of a violent street gang, the Crips. Malik was shot and paralyzed in 2018 by a bullet from a rival gang, and as a result, his world now revolves around his small apartment, where he is cared for by his family and gang members.

Gulbransen had been photographing in the Bronx during his free time and had come to know some of the local youth. He began to notice many young people in wheelchairs with spinal injuries and became professionally curious. He was told that all of them had been shot, and this curiosity led him to Malik. The images in the book are carefully selected to represent a variety of themes and situations, from the intimacy of personal moments to the grandiosity of larger environments. Gulbransen’s work is characterized by his focus on subtlety and detail, capturing moments that invite the viewer to reflect and emotionally engage. “Say Less” offers a reflective and evocative experience that reaffirms the power of images to tell meaningful stories.

After learning about the stories of many individuals like Malik, what led you to photograph him and focus on his life after the shooting?

As a physician/photographer I am inclined to pursue stories that are public health issues which need as Americans need to understand better and make policy changes. I am using both side s of my brain simultaneously (science/art) to tell the same story.

What was the biggest challenge in photographing Malik and his environment? Was there a specific moment that deeply impacted you?

As you might be aware the States are dealing with a gun violence crisis which is quite frustrating for all of us. Today the number one killer of youth in America is gun violence and the number one demographic is the black inner city population who belong to gangs. These communities need to be better understood so policy changes can be developed to help the vicious cycle of violence. I saw Malik’s story as a perfect way to help tell the story about this public health crisis.

How did Malik, his family, and the gang members react to your presence and the photographs you took? Were there any unexpected or significant reactions?

There is an image of Malik in his chair in the hallway showing the damage he does to the wall as he moves about. This shows how as a victim of gun violence Malik is now trapped and it is also a metaphor for how these inner city youth are stuck in they world of gun violence and again how the ENTIRE COUNTRY is stuck trying to best deal with it.

What do you hope viewers will learn or understand through the photographs in Say Less? Is there a specific message you want to convey?

The challenges were many and included the logistics of getting to and from the city from my home, the my safety and the safety of my camera gear, access to certain people who were with Malik in his room and the long waits between important events that randomly occurred such as court appearances, arguments, etc.

What impact do you believe gun violence has on the daily lives of people in the Bronx, and how is this reflected in your work?

The times when I was most moved emotionally was when Malik’s family/friends changed his diapers and catheterized him. Those were always sad times.

Your work focuses on the life of someone trapped in a cycle of violence. How do you see the relationship between photography and activism in addressing social issues like gun violence?

Malik’s family and I were close from the very beginning because I was very kind to them and they very much wanted his story told. As the years passed we became even closer. There were times when I would visit and not even have my camera gear.

Is there anything you’ve learned about yourself or about documentary photography while working on this project?

Anyone who felt uncomfortable with my camera received full respect and never had their photo taken. I did not want any tension with these characters at all!

In your photographic work, you have addressed complex issues like gun violence and the consequences of shooting injuries. How do you integrate your medical knowledge into the visual narrative of your projects to provide a deeper and more nuanced perspective on these topics?

My goal was expose the dangerous world of gun violence and specifically this inner city, black community with gangs and guns and how these people are born into this world. They are doomed from the very beginning. These black youths are 17 times more likely to be killed by a gun then their equivalent aged white counterparts. This issue is very complicated and we need to understand it better and not stereo type the community.

When dealing with issues that intersect violence with personal experiences in your projects, how do you assess the impact of your work on both the communities you document and the general public?

At first I thought my personal life was not a part of the story and that I was simply a physician from the outside telling an important public health story. It was not clear until much later when I saw the trauma of accidentally killing my two year old son in an accident and that dealing with those demons was where I was inside the story. It was life on the edge of death and it was very hard. The camera lets us see these demons up close and helps us deal. Most good art involves trauma somewhere.

Photography is extremely powerful as we see this daily online. People pay attention to good images and particularly to a collection of images that tell an important story. I would never suggest that this book answers or fixes any social issues but I can say that it is the only photo book of its kind. I have given a signed copy to many policy makers in America, including the US Surgeon General with the hope that we will open some eyes on this issue.

I am not sure if this will ever make a significant t social change as so many famous documentary photographers have tried in the past (Eugene Richards, Eugene Smith, etc). Photography is hard to predict as the impact of a particular image may not be realized for many years.

I have learned that documentary photography is deep and difficult. The photographer must put aside their preconceived ideas and prejudices and tell the story as objectively as possible. Go slow, listen, wait, look and be respectful. Understand the environment and the people whose story you are telling. Ask for feedback along the way from insiders and even outside friends to check your work. Shoot with lots of depth and breath to capture things you might not even see until after you are gone. Take breaks then return as many times as possible.

This book does address very well the consequences of gun violence as I tell Maliks story after he was shot in the thoracic spine and left as a paraplegic confined to bed and his wheelchair. There are several other people featured in the book who later turned to drugs to deal with their gun shot injuries and Malik’s best friend who was shot in the abdomen and was left with a colostomy bag.

Do you believe your work can constructively contribute to opening up discussions about this topic and questioning social models?

My medical knowledge with this story started because I was concerned as to why so many young people were in wheelchairs in this section of the Bronx which is something I had never seen before as a physician. How did everyone become so handicapped I wondered? It was then that my investigation lead me to realize that many of these people were victims of gun shots. With Malik I then focused on his medical care which involved catheters, diaper changes, kidney infections where required hospitalizations, wound care, dressing changes and the like. Having cared for handicapped patients before I understood these issues and felt comfortable using the camera during these times.

It is very difficult to objectively measure the impact my work on the community and the general public with this story. My goal now is not to move on to a new story but instead to stay with this topic to speak publicly about gun violence and how to is killing so many young people in America. I do feel that this story is very unique and will contribute to this ongoing discussion about this public health emergency. Say Less is an extremely different type of photo book as the story inside as told by Bill Shapiro, (Editor in Chief, Life Magazine) is just so complex and rivetin