ENTREVISTA A SUSAN A. PHILLIPS

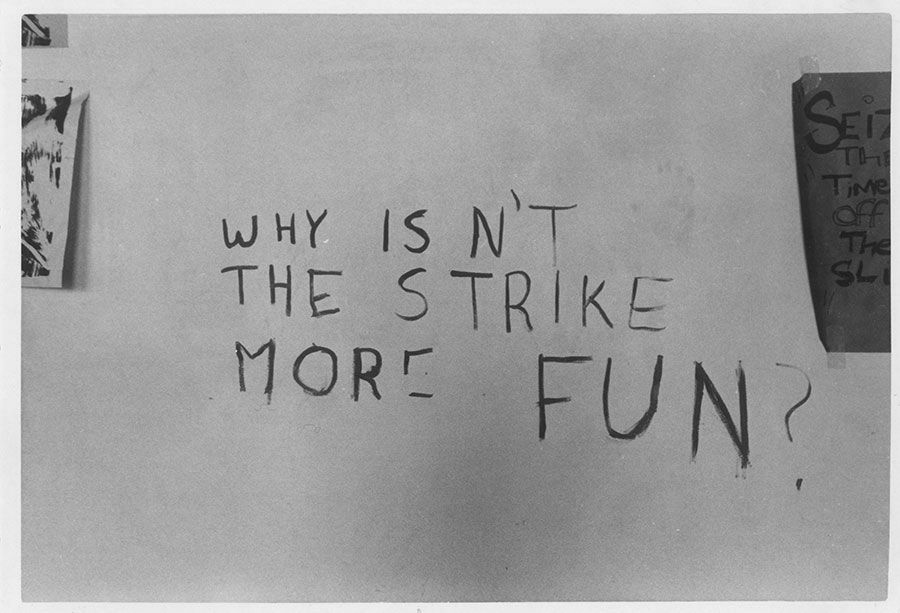

{english below} THE CITY BENEATH: A CENTURY OF LOS ANGELES GRAFFITI es un excelente trabajo de investigación teórico y fotográfico de Susan A. Phillips, cuidadosamente editado por Yale University Press, New Haven and London. Podría definirse muy sintética pero acertadamente como un libro de memorias. Después de sumergirme entre sus páginas cargadas de textos rigurosos entre los que se entremezclan eventos de la historia de la ciudad de Los Angeles durante el siglo XX con relatos personales acaecidos durante diferentes momentos de esta época asociados al grafiti histórico; uno tiene la impresión de haber asistido a una clase magistral, emocionante, sorprendente y tremendamente veraz sobre una visión no muy explorada antes, de acercarse a la historia de un lugar partiendo de las inscripciones que sus habitantes han ido dejando en el espacio público a lo largo del tiempo. Phillips, durante tres décadas, ha realizado la labor de toma y compilación de fotografías e historias, que consecuentemente le han obligado a convertirse en una gran exploradora urbana. Ha categorizado cronológica y sociológicamente el contenido recopilado, y además, tirando del hilo de muchas de estas historias, ha logrado rescatar auténticos relatos de aventuras propios de Jack London. En este libro no vamos a encontrar un pastiche de imágenes pobremente fechadas y catalogadas, por el contrario, lo que observamos, es una narración inteligentemente trazada, repleta de microhistorias olvidadas de gentes del lugar que eran desconocidas incluso por sus propios familiares. El grafiti, en este caso, desde el asociado a la cultura hobo americana hasta el más autóctono como el de los cholos -pasando por épocas concretas como el bombardeo de Pearl Harbor o la eclosión del surf o el punk- es la base sobre la cual se investigan cuestiones históricas y antropológicas que definen la identidad de este territorio. “Graffiti is an artifact of travel” así comienza la conclusión de este libro y podría ser. también su introducción. Con todo esto, y los magníficos documentos fotográficos presentes en el libro aún en la retina, hablamos con Susan A. Phillips al respecto.

Hola Susan, primero agradecerte tu tiempo y, sobre todo, darte la enhorabuena por la publicación de este brillante trabajo ¿Podría contarnos brevemente quién es Susan A. Phillips y de dónde proviene el interés por el grafiti, llamémosle, histórico?

¡Gracias! Estoy emocionada de ser entrevistada por una revista tan genial. En cuanto a quién soy: soy hija de una madre italiana (una historiadora del arte, nacida en Roma que vino a Los Ángeles vía Venezuela) y un padre inglés (un ingeniero de taller mecánico, nacido en Liverpool que vino a Los Ángeles a través de Toronto ). Mi casa era plurilingüe: llena de libros de arte, buena ficción, discos, cámaras viejas, un piano y guitarras. Me crié en una zona suburbana del sur de California que me pareció cada vez más aburrida a medida que envejecía. Los suburbios me llevaron a terminar en entornos urbanos más vanguardistas, por mi supervivencia existencial. Heredé el amor de mi madre por las áreas industriales cercanas a donde vivíamos que tenían refinerías de petróleo, fábricas y el puerto industrial. En la universidad, estudié Historia del Arte y Antropología y me interesé profundamente en el arte de grupos de la costa noroeste como los Tlingit, Coast Salish y Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl). Mi estudio del arte también abarcó las tradiciones europeas: antigua, renacentista, medieval, así como otras formas de arte no occidentales. Estudiar elementos simbólicos y estéticos en una variedad de sociedades finalmente me llevó al grafiti. Estaba buscando el vínculo intrínseco entre el arte y la vida social que vi en ciertas culturas y períodos de tiempo, y me preguntaba dónde estaba en mi propia sociedad. Sabía que no estaba en el museo, eso estaba demasiado distanciado de la vida cotidiana ¿Fue en la publicidad, en el cine…? Accidentalmente lo encontré en el grafiti de pandillas de Los Ángeles. La escritura de pandillas era un modo altamente estético de expresión visual, indeleblemente ligado a la vida social, a la vida y a la muerte en realidad. Realmente nunca miré hacia atrás. Lo curioso es que siempre he sido una persona respetuosa con la ley, por lo que nunca me atrajeron las pandillas o el grafiti como algo romántico. En general, soy un poco cuadriculada, aunque ahora hago muchas más cosas de las que solía hacer. Conocí a todo tipo de personas increíbles, visité lugares inimaginables y he trabajado mucho en torno a cuestiones de justicia social relacionadas con la desigualdad y el encarcelamiento.

He definido este trabajo como un libro de memorias de un lugar, no sé si he acertado, así que cuéntenos, ¿cuál es el objetivo que tenías al comenzar este trabajo?

La idea de este trabajo como un libro de recuerdos me parece acertada. Cuando era niña, teníamos latas de memoria en las que poníamos objetos que eran importantes para nosotras. Esto es algo así, excepto que en este caso son todo tipo de personas, separadas por el tiempo y el contexto. Y sí, todo gira alrededor de la infraestructura de Los Ángeles y su entorno construido a lo largo de un siglo. Cuando comencé el trabajo de campo, hace más de veinte años, mi objetivo era documentar la mayor cantidad posible de grafitis históricos. En 2013, me di cuenta de que tenía una muestra de grafiti de cada década del siglo XX desde 1910, y el grafiti más antiguo que encontré estaba a punto de cumplir cien años. Inicialmente imaginé escribir un pequeño libro de fotos basado en imágenes. Pero pronto descubrí que necesitaba saber más; literalmente, no pude detenerme. Esto acabó en un proceso de escritura de cinco años y un libro mucho más largo.

Uno de los aspectos más interesantes del libro son las historias, en ocasiones personales, que subyacen de cada época, ¿cómo ha sido el proceso de investigación, escritura y compilación de material para conformar este libro?

El proceso de investigación fue como tener una historia de amor con cada capítulo, ahondé en cada tema. Me pregunté qué necesitaba saber para comprender los distintos escritos y piezas de grafiti. A veces tuve suerte porque la gente escribía sus nombres completos; entonces podía hacer una investigación censal y descubrir todo tipo de cosas sobre ellos. En ocasiones pude contactar a los propios escritores y, otras, logré localizar a un pariente o dos, fue un proceso increíble. Soy antropóloga, me encantan las personas y sus historias, pero este formato en particular realmente me entusiasma; las palabras, las firmas y las historias se fusionan con el entorno construido, siendo todo parte de la estructura de la ciudad, esta combinación fue adictiva para mí. Me mantuve firme en el camino a la producción de este libro y, en esencia, hacia escribir una nueva historia de la ciudad. Recuerdo alrededor del tercer año de escritura que solo quería vivir en este proceso para siempre. Pensé que tal vez podría continuar mis exploraciones urbanas, hablar con la gente, hacer investigaciones de archivo y seleccionar imágenes visuales para el resto de mi vida, pero, al final, se volvió demasiado. Corté tres capítulos, porque el libro era demasiado largo. El capítulo sobre punk rock casi no sucedió debido al agotamiento. Pero me encantan todos los capítulos, cada uno a su manera, así que me alegro de haber podido avanzar y finalmente hacerlos.

De esta lectura deduzco, también porque en ocasiones usted comenta que iba acompañada de su familia, que ha sido un trabajo íntimamente ligado a su vida durante un largo período de tiempo, ¿qué ha aprendido y qué cree que podría aprender el lector?

Sí, este trabajo, definitivamente, ha sido a largo plazo y ha involucrado a mi familia desde el principio. En total, para mí, es un proyecto de treinta años. Tomé mi primera fotografía de grafiti de pandillas en octubre de 1990 y luego comencé en serio con el grafiti histórico, en 1997. Tengo la suerte de haber tenido un esposo e hijos comprensivos. Piensan que estoy loca la mitad del tiempo pero han venido a muchas aventuras conmigo. El proyecto realmente ha dado forma a quién soy. He aprendido a ver la ciudad de una manera diferente. He aprendido a ver la belleza en lugares inusuales, a encontrar poder al margen de la sociedad. Eso es algo esperanzador para mí, porque me permite valorar la expresión de las personas denigradas o vilipendiadas por la sociedad. He pensado mucho sobre lo que significa el grafiti en el mundo ahora y en el pasado. Históricamente, el grafiti ha sido un símbolo de una vida social fuerte, que ha disminuido dramáticamente en el siglo XX. Hoy, el grafiti, es en gran medida un esfuerzo anticapitalista. Y cuanto más continúen las cosas en términos de privatización y neoliberalismo, el crecimiento de la desigualdad global, el cambio climático y los impactos desproporcionados de los problemas sociales, económicos y ambientales del mundo, más vamos a necesitar modelos diferentes y formas de conexión social que no traten sobre el consumo. El grafiti es parte de eso. Representa el poder desde los márgenes, escrito por un conjunto diferente de reglas. Necesitamos más de eso. De este proyecto aprendí a ver el poder en cosas simples y la belleza en lugares inusuales. Espero que los lectores se lleven esas cosas y más. Nuestro concepto de grafiti está muy limitado en este momento. Espero ampliar la forma en que las personas ven la historia y el grafiti con este trabajo.

En lo referente a la bibliografía relacionada tanto al grafiti como al street art, estamos acostumbrados a ver en librerías obras superficiales y carentes de contenido mientras que, en esta ocasión, nos acercamos más a un libro de relatos que a un frío análisis del fenómeno del grafiti; sin embargo, analiza aspectos como las flechas, los números, el estilo, etc. ¿Cuánto interés dedicó a la cuestión estética y a su evolución y de dónde extrajo o cómo dedujo dicha información?

El estudio de la estética ha ido aumentando y disminuyendo. Mi proceso analítico es siempre una combinación de investigación empírica fundamentada e intuición que, a día de hoy, está bastante perfeccionada. Para mí, las historias son parte de esa base empírica; simplemente no es la forma en que tendemos a escribir sobre grafiti. En términos de estética, toda mi investigación se basa en el análisis visual del material en sí mismo, así como en cualquier material de escritura o fuente primaria que lo defina. No estoy tan obsesionada con el desarrollo de trayectorias estéticas particulares como algunos de mis colegas investigadores de grafiti. Debido a que los elementos estéticos y simbólicos en el grafiti tienden a ser repetitivos, las pistas a menudo se dan en las propias piezas. Por lo tanto, solo puedo prestar atención al contenido de cualquier grafiti y deducir significados, pero también tienes que hablar con la gente para obtener toda la historia. Varios de los géneros que cubro en el libro son completamente desconocidos y nunca antes se había escrito sobre ellos. Así que tuve que confiar tanto en mi propia experiencia en el examen de materiales similares como en mi trabajo de etnógrafa. Esto fue así para los capítulos sobre trabajadores de Hollywood y marineros de portacontenedores: ambos tienen tradiciones de grafiti increíblemente ricas y antiguas que abarcan la mayor parte del siglo XX, pero pocas personas saben sobre ellos. Siempre me ha encantado cuando veo cosas que nunca antes había visto o cuando encuentro cosas que no puedo entender o cuando veo un nuevo sistema de escritura. Eso significa que hay un misterio, un rompecabezas para armar, una historia que contar.

Debido al influjo del street art o el grafiti actuales, han ido desapareciendo muchas inscripciones históricas. Esta cuestión abre un debate interesante, la pregunta de qué se debe conservar y qué no, quién lo decide y cómo; por ejemplo, pintadas sobre monumentos y la importancia que se le otorga según su antigüedad, ¿Qué opina al respecto? ¿Cree que inscripciones que hoy día se realizan sobre otras más antiguas tendrán su mismo valor dentro de un tiempo determinado? ¿Es esto inevitable?

Lo principal del grafiti es su condición efímera. Se produce en el momento y no necesariamente debe ser duradero. Por eso es tan especial cuando el grafiti comienza a informarnos sobre la historia. Antes del capitalismo industrial, las sociedades sabían leer y escribir pero carecían de papel. El grafiti era una parte importante de la expresión social, y en su mayor parte no se consideraba vandalismo. El papel del grafiti ha cambiado ahora para convertirse en un modo de expresión en gran medida ilegal, a menudo utilizado por personas al margen de la sociedad. Mi propia opinión sobre el tema de la conservación ha cambiado como resultado de este proyecto. Solía consumirme con preocupación por algunas de las primeras inscripciones de grafiti que había documentado pero que no podía proteger. Ahora veo que las inscripciones tienen su propia trayectoria temporal; viven sus propias vidas, por así decirlo. Creo que el grafiti histórico en monumentos o en otros lugares es increíblemente importante y merece documentación. Todo necesita ser estudiado, debido a la forma en que el grafiti abre nuestra visión de la historia y nuestra visión del mundo; pero hoy me preocupo menos por la conservación real. El archivo de cualquier pieza en particular puede ser fotográfico y eso es lo suficientemente bueno para mí. De lo otro, de cuánto se ha perdido, poco sabemos… Una cosa que desearía es que los escritores de grafiti fotografiaran cualquier grafiti histórico que encuentren antes de escribir sobre el, pero probablemente sea demasiado tarde para eso. He tenido que aceptar la tensión entre la escritura contemporánea, el blanqueo municipal y la escritura histórica. Y ciertamente la escritura contemporánea de hoy se volverá histórica en algún momento, un objeto de nostalgia. Pero la diferencia es cuán ampliamente estudiados son el grafiti contemporáneo y el arte callejero, mientras que los géneros de grafiti menos conocidos fuera de esa estrecha ventana se quedan en el camino.

Sabemos que, a lo largo de la historia, las inscripciones sobre muros y otros soportes similares han sido el modo de expresión más crudo y directo. Después de una investigación como la suya, ¿piensa que sigue teniendo sentido hoy día, en un mundo que socialmente se vertebra en gran parte de manera virtual?

Absolutamente. Si lo piensas, la base del grafiti en los mundos virtuales es analógica. Está en el mundo real. Todo en el mundo tiene la posibilidad de desaparecer o ser despojado. Pero aún se tiene la capacidad de tomar un palo quemado, o una piedra, o un trozo de tiza, y escribir algo en una pared. Las personas tienen una necesidad fundamental de expresarse, tanto individual como colectivamente. Dependiendo de las circunstancias, el grafiti puede convertirse en una parte importante de eso. Piense en un prisionero al que le han arrebatado todo. Piense en grupos de niños en la calle tratando de hacerse un nombre en medio de la profunda alienación de nuestro mundo. Las redes sociales pueden contrarrestar esa alienación a veces, pero también producirla. El capitalismo tardío es un entorno tremendamente insalubre que necesita ser desafiado. Y creo que el grafiti es una forma de hacerlo. Parte de nuestro mundo está virtualmente estructurado, pero la gran mayoría no lo está. Todavía confiamos en el parentesco y la comunidad para sobrevivir, y tengo la sensación de que la importancia de éstos, junto con los modos de expresión analógicos como el grafiti, seguirá estando ahí en el futuro.

Otro de los aspectos que destaco de este trabajo frente a otros es su limitación espacio-temporal. Poder decir que es un libro creíble, pienso que es su gran éxito. ¿Tendría sentido hacer un trabajo así sin conocer de forma tan profunda el territorio que se trata?

Muchas gracias. De hecho, yo también me he preguntado esto mismo. He vivido en Los Ángeles toda mi vida y mi conocimiento personal y académico de la ciudad es extenso, eso lo recoge claramente el libro. Dicho esto, pensé que sabía mucho sobre Los Ángeles antes de comenzar a escribir este libro y aprendí mucho como resultado de ello. Además, coleccioné grafiti histórico en las últimas décadas, pero realmente aumenté durante los cinco años en los que estaba escribiendo. Por lo tanto diría que cualquier persona que tenga la intención de documentar y escribir sobre imágenes antiguas de grafiti debería hacerlo, sin importar si es un recién llegado o un residente permanente del lugar; es un campo abierto. Todos aportan una lente única al tema. Espero que más personas se embarquen en estudios de este tipo, me encantaría leer tratados similares de ciudades de todo el mundo como París, Londres, Madrid o Roma, o de pueblos pequeños, o sobre géneros y sistemas simbólicos o estilos de fuente de los que nunca haya oído hablar. Hay personas interesadas en este tipo de trabajo fuera de género y me encantaría escuchar en qué están trabajando y, así, aprender de ellos sobre este peculiar modo de expresión que traspasa el tiempo y el lugar.

Al hilo de la última pregunta, y hablando del grafiti o el street art genuino como manifestaciones esencialmente contextuales, ¿qué opinión le merecen estos movimientos en la actualidad y qué diferencias podría establecer entre ellos en relación a las tipologías que trata en su libro?

En este punto, los libros académicos populares están saturados de tradiciones y excluyen casi todo lo demás. Estoy agotada de la estética del grafiti contemporáneo. A veces me irrita la forma en que las tradiciones de Nueva York simplemente han eclipsado las tradiciones de escritura más antiguas u otras formas de escritura en todo el mundo. Lo veo como una pérdida tremenda pero, al mismo tiempo, me encantan los escritores de grafiti contemporáneos, la mitad de ellos son locos, obsesivos, compulsivos, lo que sea, pero interactúan con la ciudad de maneras inusuales y subvierten el funcionamiento convencional del mundo. De hecho, me encantan los tags simples de una sola línea más que cualquier otra cosa, y me encantan los throw-ups, no tanto las piezas. Los verdaderos bombers son personas increíbles para mí. Tienen perspectivas interesantes y son geniales para hablar sobre la vida. Ven la ciudad de una manera completamente diferente. Tengo algunos amigos cercanos que son bombers y son algunas de mis personas favoritas. Espero que, en el futuro, las personas que escriban sobre grafiti incluyan historias de escritores y la competencia o cooperación entre ellos y no solo presten atención a la estética del fenómeno.

Tendría muchas más preguntas que formular, pero voy a permitir que sean los lectores los que acudan a su trabajo y saquen sus conclusiones. Muchas gracias y si quisiera comentar algo más …

Estoy agradecida por la oportunidad de interactuar con el público español a través de la revista Staf. España tiene una rica tradición de grafiti político sobre la independencia vasca y, Europa, en general, tiene la mayor tradición en curso y la idea de que el grafiti como fenómeno no comienza en la década de 1970 en Nueva York y termina con Banksy. Yo diría que el grafiti es algo importante que estudiar ahora. No puedes poner límites un medio que es mayormente ilegal, esto hace que la expresión sea libre e incapaz de ser controlada de arriba hacia abajo. El grafiti es una herramienta del pueblo y siempre lo será.

THE CITY BENEATH BOOK

English:

THE CITY BENEATH: A CENTURY OF LOS ANGELES GRAFFITI is an excellent theoretical and photographic book by Susan A. Phillips, carefully edited by Yale University Press, New Haven and London. It could be defined very synthetically, but correctly, as a memory book. After immersing myself among its pages loaded with rigorous texts, among which events of the history of the city of Los Angeles during the 20th century are intermingled with personal stories that occurred during different moments of this time, associated with historical graffiti; I have the impression of having attended an exciting, surprising and tremendously truthful master class on a way, not very explored before, of approaching the history of a place based on the inscriptions that its inhabitants have been leaving in public space for the long of the time. Phillips has worked for three decades, taking and compiling photographs and stories, which have consequently forced her to become a great urban explorer. He has chronologically and sociologically categorized the collected content, and also, pulling the thread of many of these stories, he has managed to rescue authentic tales of adventures typical of Jack London. In this book we are not going to find a mix of poorly dated and cataloged images, on the contrary what we observe is an intelligently plotted narration, through which underlying forgotten little stories of local people, which were unknown even by their own relatives. The graffiti, in this case, from the one associated with the American hobo culture to the most indigenous one like the cholos -passing through specific times such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor or the emergence of surfing or punk movements- is the basis on which Historical and anthropological questions that define the identity of this territory are investigated. “Graffiti is an artifact of travel” is how the conclusion of this book begins, and how its introduction could also begin. With all this, and the magnificent photographic documents present in the book still on my mind, we speak with Susan A. Phillips about it.

Hello Susan, firstly, thank you for your time and, above all, congratulations on the publication of this brilliant work. Could you tell us briefly who Susan A. Phillips is and where the interest in graffiti comes from, let’s call it, historical?

Thank you! I’m excited to be interviewed by such a cool magazine. As to who I am: I’m the daughter of an Italian mother (an art historian, born in Rome who came to Los Angeles via Venezuela) and English father (a machine shop engineer, born in Liverpool who came to Los Angeles via Toronto). My house was multilingual: full of art books, good fiction, records, old cameras, a piano, and guitars. I was raised in a suburban part of Southern California that I found increasingly boring the older I got. The suburbs drove me toward more edgy urban environments as a matter of existential survival. I inherited my mother’s love of industrial areas near where we lived that had oil refineries, factories, and the industrial harbor. In college, I studied art history and anthropology and became deeply interested in the art of Northwest Coast groups such as the Tlingit, Coast Salish, and Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl). My study of art also encompassed European traditions ancient, renaissance, medieval as well as other nonwestern forms of art. Studying symbolic and aesthetic elements across a variety of societies ultimately led me to graffiti. I was looking for the intrinsic tie between art and social life I saw in certain cultures and time periods, and I wondered where it was in my own society. I knew it wasn’t in the museum that was too divorced from every day life. Was it in advertising? Film? I accidentally found it in L.A. gang graffiti. Gang writing was a highly aestheticized mode of visual expression indelibly tied to social life to life and death, really. I never really looked back. The funny thing is that I have always been very a straight laced and law-abiding kind of person so I was never attracted to gangs or graffiti as some kind of romanticized thing. I’m still kind of square on the whole, although now I do a lot more trespassing than I used to. I’ve met all kinds of amazing people, visited incredible places, and have done a lot of work around social justice issues surrounding inequality and incarceration.

I have defined this work as a memory book of a place, I do not know if I have been right, so tell us, what is the objective you had when starting this work?

The idea of this work as a memory book rings true for me. When I was a kid, we had memory cans into which we’d put objects that were important to us. This is kind of like that, except the curators are all kinds of people, separated by time and context. And yes, place ties all of it together through the infrastructure of Los Angeles and its built environment over the course of a century. When I first started the fieldwork over twenty years ago, my objective was to document as much historic graffiti writing as possible. By 2013 I realized I had a sampling of graffiti from every decade of the 20th century since 1910 and the oldest graffiti I had found was about to turn 100. I had initially envisioned writing a short photo book that was image driven. But I soon found that I needed to know more; I literally couldn’t stop myself. This resulted in a five years writing process and a much longer book.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is the stories, sometimes personal, that underlie each period. How has the research, writing and compilation of material to form this book been?

The process of research was like having a love affair with each chapter. I’d do these deep dives into each topic. I asked myself what I needed to know to understand any given piece of writing or a cluster of graffiti material. Sometimes I lucked out because people wrote their full names. I could then do census research and find out all kinds of things about them. Sometimes I was able to contact the writers themselves, and sometimes I managed to track down a relative or two. That was an incredible process. I’m an anthropologist. I love people and people’s stories. But this particular format really fires me up—where words, signatures, and stories are all fused to the built environment, all part of the city’s fabric. That combination was intoxicating for me. It kept me solidly on the path toward producing this book and in essence to write a new history of the city. I remember at about year three of writing that I just wanted to live in this process forever. I figured maybe I could continue my urban explorations, talk to people, do archival research, and pick apart visual images for the rest of my life. But by the end, it became too much. I cut three chapters out, because the book was too long. The chapter on punk rock almost didn’t happen due to burnout. But I love all of the chapters in different ways, so I’m glad I was able to push through and finally get the thing done.

From this reading I deduce – also because sometimes you comment that you were accompanied by your family – that it has been a job closely linked to your life for a long period of time, what have you learned and what do you think the reader could learn?

Yes, this work has definitely been long term and has involved my family from the very beginning. All told, it’s a thirty-year project for me. I took my first picture of gang graffiti in October 1990, and then began in earnest with historical graffiti in 1997. I’m lucky to have had an understanding husband and kids…they think I’m crazy half the time but they have come on lots of adventures with me. The project has really shaped who I am. I have learned to see the city in a different way. I have learned to see beauty in unusual places, to find power at the fringes of society. That is a hopeful thing for me, because it enables me to value the expression of people denigrated or vilified by society. I have thought a lot about what graffiti means in the world now and in the past. Historically, graffiti was a symbol of a robust public life, which has diminished dramatically in the 20th century. Today, graffiti is a largely anti-capitalist endeavor. And the more things continue in terms of privatization/neoliberalism, the growth of global inequality, climate change, and the disproportionate impacts of the world’s social, economic and environmental problems, the more we’re going to need models that are different and forms of social connection that are not about consumption. Graffiti is part of that. It represents power from the margins, written by a different set of rules. We need more of that. From this project I’ve learned to see power in simple things and beauty in unusual places. I hope that readers will take away those things and more. Our graffiti world is so narrowly defined right now. I hope to expand people’s way of seeing both history and graffiti with these materials.

Regarding the bibliography related to both graffiti and street art, we are used to seeing superficial works in bookstores and lack rigorous content, while this time we are closer to a book of stories than to a cold analysis of the phenomenon graffiti; However, it analyzes aspects such as arrows, numbers, style, etc. How much interest did you devote to the aesthetic issue and its evolution and where did you extract or how did you deduce this information?

I’ve waxed and waned when it comes to the study of aesthetics. My analytical process is always some combination of grounded, empirical research and intuition, which by now is pretty well honed. To me, the stories are part of that empirical basis; it’s just not the way we tend to write about graffiti. In terms of aesthetics, all of my analysis is based on visual analysis of the material itself as well as any writing or primary source materials that already define it. I’m not nearly as obsessed with the development of particular aesthetic trajectories as some of my fellow graffiti researchers are. Because aesthetic and symbolic elements in graffiti tend to be repetitive, clues are often written into pieces themselves. So you just can pay attention to the contents of any given piece of writing and deduce meanings. But you also have to talk to people to get the whole story. Several of the genres I cover in the book are completely unknown and have never before been written about. So I had to rely on both my own experience in examining similar materials but also my work as an ethnographer. This was true for the chapters on Hollywood workers and containership sailors both have incredibly rich, longstanding graffiti traditions of graffiti that span most of the 20th century but few people even know about them. I always love it when I see stuff I’ve never seen before or find things I can’t understand or get to look at a new lettering system. That means there’s a mystery out there, a puzzle to piece together, a story to tell.

You say in the introduction that, due to the influence of current street art or graffiti, many historical inscriptions have disappeared. This question opens an interesting debate, since the question of what should be preserved and what not, who decides and how, for example, about graffiti on monuments and the importance given to it according to its antiquity, is very present. What do you think about that? Do you think that inscriptions that are made today on older ones will have the same value within a certain time? Is this inevitable?

The main thing about graffiti is its ephemerality. It’s produced in the moment and is not necessarily meant to be lasting. That’s why it’s so special when graffiti begins to inform our understanding of history. Before industrial capitalism, societies were literate but lacked paper. Graffiti was an important part of social expression, and for the most part was not considered vandalism. The role of graffiti has changed now to become a largely illegal mode of expression often used by people on the fringes. My own take on the subject of conservation has changed as a result of this project. I used to be consumed with worry over some of the early graffiti marks I had documented but couldn’t protect. Now I view the marks as having their own temporal trajectory; they live their own lives so to speak. I do think that historic graffiti on monuments or in other locations is incredibly important and deserving of documentation. It all needs to be studied, because of the way that graffiti opens our vision of history and our view of the world. But today I worry less about actual conservation. The archive of any particular piece can be photographic and that’s good enough for me. The other thing is coming to terms with how little we know how much has already been lost. One thing I’d wish for is that graffiti writers would photograph any historic writing they find before writing over it but it’s probably too late for that now anyway. I’ve had to come to terms with the tension between contemporary writing, municipal whitewashing, and historic writing. And certainly the contemporary writing of today will become historic at some point an object of nostalgia. But the difference is how widely studied contemporary graffiti and street art are, while lesser known genres of graffiti outside of that narrow vantage are left by the wayside.

We know that throughout history, inscriptions on walls and other similar supports has been the crudest and most direct mode of expression. After an investigation like yours, do you think it still makes sense today, in a world that is largely socially structured in a virtual way?

Absolutely. If you think about it, the base of graffiti in virtual worlds is analog. It’s in the real world. Everything in the world has the possibility of disappearing or being stripped away. But you still have the ability to take a burned stick, or a rock, or a piece of chalk and write something on a wall. People have a fundamental need to express themselves, both as individuals and collectively. Depending on the circumstances, graffiti can become an important part of that. Think of a prisoner from whom everything has been taken. Think of groups of kids on the street trying to make names for themselves amidst the profound alienation of our world. Social media may counter that alienation sometimes, but it also produces it. Late capitalism is a tremendously unhealthy environment that needs to be challenged. And I think graffiti is one way to do that. Part of our world is virtually structured, but the vast majority of it is not. We still rely on kinship and community to survive, and my sense is that the importance of these, along with analog modes of expression like graffiti, will remain important into the future.

Another aspect that I highlight of this work compared to others is its spatio-temporal limitation. I think the authenticity of this book is its great success. Would it make sense to do a work like this without knowing so deeply the territory in question?

Thank you so much for that. I’ve actually wondered about that too. I’ve lived in Los Angeles all my life, and my personal and academic knowledge of the city is extensive. That knowledge clearly informs the book and the depth of analysis. That said, I thought I knew a lot about L.A. before I started writing this book, and I learned a massive amount as a result of it. Also, I did collect historical graffiti over the past few decades but I really ramped up during the five years in which I was writing. So I’d say that anyone with a mind toward documenting and writing about older graffiti images should do so, no matter if they’re a newcomer or lifelong resident of a place. It’s a wide open field. Everyone brings a unique lens to the subject. I hope more people will embark on studies of this kind. I’d love to read similar treatments of global cities like Paris, London, Madrid, or Rome, or in small towns, or about genres and symbolic systems or font styles that I’ve never heard of. There are a handful of people interested in this kind of out-of-genre work, and I love hearing what they’re working on and learning from them about this quirky mode of expression that crosscuts time and place.

In line with the last question, and speaking of graffiti or genuine street art as essentially contextual manifestations, what opinion do these movements deserve at present and what differences could they establish between them and in relation to the typologies that they deal with in their book ?

At this point, academic and popular books are saturated with those traditions to the exclusion of almost everything else. I’m so burnt out with the aesthetics of contemporary graffiti. I’m sometimes irritated by the way that New York traditions have simply eclipsed older writing traditions or other forms of writing all over the world. I view it as a tremendous loss. But at the same time, I love contemporary graffiti writers. Half of them are crazy, obsessive, compulsive you name it, and graffiti writers have it. But they interact with the city in unusual ways and they subvert the conventional workings of the world. I actually love simple, single-line tags more than anything else, and I love throwies. Piecing I’m not so crazy about. True bombers are incredible people to me. They have interesting worldviews, and are great to talk to about life. They see the city in an entirely different way. I have some close friends who are bombers and they are some of my favorite people. My hope is that, in the future, people who write about graffiti will include the stories of writers, and the competition or cooperation between crews, and not just pay attention to the aesthetics of the phenomenon.

I would have many more questions to ask, but I am going to allow the readers to come to this work and draw their conclusions. Thank you very much and if you would like to comment something else…

I’m grateful for the chance to interact with a Spanish audience through Staf Magazine. Spain has such a rich tradition of political writing and Basque independence graffiti. Europe in general has broader ongoing graffiti traditions and an awareness that graffiti as a phenomenon doesn’t begin in 1970s New York and end with Banksy. I would say that graffiti is a critically important medium to study now. You can’t put boundaries around a medium that’s mostly illegal. It makes the expression free and unable to be controlled from the top down. Graffiti is a medium of the people, and it always will be.